What future for human rights in a non-western world?

Nevertheless, the historical development of human rights demonstrates that the relativist critique cannot be wholly or axiomatically dismissed. Nor is it surprising that it should emerge soon after the end of the Cold War. Against the backdrop of increasing human rights interventionism on the part of the UN and by regional organizations and deputized coalitions of states as in Bosnia and Herzegovina , Somalia, Liberia , Rwanda , Haiti , Serbia and Kosovo , Libya , and Mali , for example , the relativist viewpoint serves also as a functional equivalent of the doctrine of respect for national sovereignty and territorial integrity , which had been declining in influence not only in the human rights context but also in the contexts of national security, economics , and the environment.

As a consequence, there remains sharp political and theoretical disagreement about the legitimate scope of human rights and about the priorities that are claimed among them. On final analysis, however, this legitimacy-priority debate can be dangerously misleading.

Although useful for pointing out how notions of liberty and individualism have been used to rationalize the abuses of capitalism and Western expansionism and for exposing the ways in which notions of equality, collectivism, and culture have been alibis for authoritarian governance, in the end the debate risks obscuring at least three essential truths that must be taken into account if the contemporary worldwide human rights movement is to be understood objectively. First, one-sided characterizations of legitimacy and priority are very likely, at least over the long term, to undermine the political credibility of their proponents and the defensibility of the rights they regard as preeminently important.

In an increasingly interdependent global community, any human rights orientation that does not support the widest possible shaping and sharing of values or capabilities among all human beings is likely to provoke widespread skepticism. The period since the midth century is replete with examples, among them the official U. Second, such characterizations do not accurately reflect reality.

In the real world, virtually all societies, whether individualistic or collectivist in essential character, at least consent to, and most even promote, a mixture of all basic values or capabilities. A later demonstration is found in the Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action of the conference mentioned above, adopted by representatives of states.

To be sure, some disagreements about legitimacy and priority can derive from differences of definition e. Similarly, disagreements can arise also when treating the problem of implementation. For instance, some insist first on certain civil and political guarantees, whereas others defer initially to conditions of material well-being.

Such disagreements, however, reflect differences in political agendas and have little if any conceptual utility. As confirmed by numerous resolutions of the UN General Assembly and reaffirmed in the Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action, there is a wide consensus that all human rights form an indivisible whole and that the protection of human rights is not and should not be a matter of purely national jurisdiction. The extent to which the international community actually protects the human rights it prescribes is, on the other hand, a different matter.

We welcome suggested improvements to any of our articles. You can make it easier for us to review and, hopefully, publish your contribution by keeping a few points in mind. Your contribution may be further edited by our staff, and its publication is subject to our final approval.

Human rights | www.newyorkethnicfood.com

Unfortunately, our editorial approach may not be able to accommodate all contributions. Our editors will review what you've submitted, and if it meets our criteria, we'll add it to the article. Please note that our editors may make some formatting changes or correct spelling or grammatical errors, and may also contact you if any clarifications are needed. Read More on This Topic. Page 1 of 3. Next page International human rights: Learn More in these related Britannica articles: Rights accrued by virtue of belonging, in two ways: A decisive part in the elaboration of the general principles of human rights was taken by the Spanish and Portuguese theologians of the 16th and 17th centuries, especially Francisco de Vitoria.

In the 18th century Puritan leaders continued the struggle against slavery as…. Human being , a culture-bearing primate classified in the genus Homo , especially the species H. Human beings are anatomically similar and related to the great apes but are distinguished by a more highly developed brain and a resultant capacity for articulate speech and abstract reasoning. In addition, human beings display….

World War II , conflict that involved virtually every part of the world during the years — More About Human rights 42 references found in Britannica articles Assorted References contrast with civil rights In civil rights importance to Carter In 20th-century international relations: American uncertainty In 20th-century international relations: Human rights Vitoria In Francisco de Vitoria: Personal and property rights View More.

Articles from Britannica Encyclopedias for elementary and high school students. Help us improve this article! Contact our editors with your feedback. You may find it helpful to search within the site to see how similar or related subjects are covered.

There was a problem providing the content you requested

Any text you add should be original, not copied from other sources. At the bottom of the article, feel free to list any sources that support your changes, so that we can fully understand their context. Internet URLs are the best. Thank You for Your Contribution! There was a problem with your submission. Please try again later. Keep Exploring Britannica Education. Education, discipline that is concerned with methods of teaching and learning in schools or school-like….

Gender wage gap, in many industrialized countries, systemic differences between the average wages or….

In essence, human rights were conceived as instruments by which to combat oppression by autocratic rulers and exclusion from the political process. The American Declaration of Independence and the ensuing Bill of Rights were designed not only to free the American colonies from an English parliament in which they had no political representation, but also to protect future generations from the abuse of political power by any indigenous government. Similarly, the French Declaration on the Rights and Duties of Man was aimed at curtailing oppression by future governments. Intimately associated with these ideas was the concept of self-determination rooted in the notion of democratic participation in government.

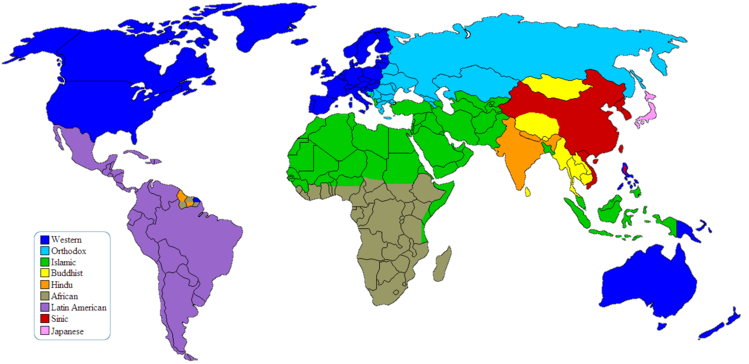

Human rights were thus initially the direct product of the evolution of the modern democratic state, and the modern democratic state is undoubtedly of Western provenance. The Western intellectual foundations of human rights are also evident in the post human rights movement. This is not to say that there was an absence of non-Western input into the Universal Declaration. The history of the drafting of the Declaration shows that there was considerable discussion about the cross-cultural acceptability of the instrument.

This observation by the American Anthropological Society introduced into the debate on human rights the notion of cultural relativism. Although cultural relativism has been appropriated as a general term to argue that all human rights are culturally derived and mediated, it has its origins in the study of anthropology, where it emerged in the early twentieth century as a reaction to the theory of cultural evolutionism.

European civilisation was, of course, seen as the pinnacle of such progress and implicit in this were racist overtones. As Hatch has written, "the people who were thought to be the least cultured were also thought to be the least intelligent and the darkest in pigmentation". The effect of cultural relativism, in an anthropological sense, is to challenge absolute and universalist conceptions of morality and to promote tolerance of other cultures. As Renteln argues, however, it is a mistake to think that tolerance requires us to tolerate everything.

She says, "the key point is that the theory of ethical relativism as descriptive hypothesis is not a value theory but rather a theory about value judgments". Since there is no universal culture, but rather a broad array of cultures, there can, in consequence, be no single, universally valid standpoint on any moral issue. Furthermore, because human rights are a species of moral entitlement, they cannot have a universal quality, but must vary according to the cultural environment in which they originate and function.

To take this argument a little further, since human rights are essentially the product of Western culture or, more specifically, Western political philosophy, their application to non-Western cultures or philosophies must be open to question. The principle of the universality of human rights, which is expressed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other United Nations instruments, is posited upon certain assumptions about the fundamental nature of all human beings.

It assumes that since all people possess the same essential human qualities, every person must, in consequence, be of equal dignity and worth and thus equal in rights. Although this assumption is the subject of considerable philosophical and jurisprudential debate, [18] it none the less finds support not only in a variety of national and international human rights instruments, but also, to a certain degree, in a number of theological and philosophical traditions.

Certainly, these ideas can be discerned in Christian traditions, particularly that of the social teaching of Roman Catholicism, [19] and while other traditions may be duty rather than rights-based, none the less, the intrinsic dignity and worth of the human person remain central elements of their doctrines. Within the UN human rights system, however, it follows that because all people are equal in dignity and worth they also possess those human rights in equal measure.

The logical corollary of this is that human rights are universal in character; that is, they apply to all people regardless of location, time or personal characteristics. This view is not only stated explicitly in the Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action , [20] it is also supported implicitly by the broad anti-discrimination provisions of the major human rights instruments. Article 2 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, for example, provides:.

It is one thing to say that human rights are possessed equally by all human beings the world over, but quite another to say exactly what those right are and how they stand in relation to each other. In the present context these are particularly important issues. In its pure or absolute form [21] the principle of universality would not allow any variation in the application rights; there would have to be a uniform application of those rights.

Furthermore, the Vienna Declaration And Programme of action states that since human rights are "indivisible and interdependent and interrelated" the international community must treat them "in a fair and equal manner, on the same footing and with the same emphasis". To put it another way, human rights are horizontally integrated and mutually supportive.

This suggests that the argument by some Asian governments that the right to development must take priority over certain civil and political rights is, on this understanding of the universality and equal application of all rights, unsustainable. Following the examination of universality and relativity above, it will be apparent that the two theories in their extreme or radical forms stand diametrically opposed to each other.

Absolute universality would seem to require total uniformity in the enjoyment of all human rights by all human beings, whereas absolute relativity implies an absence of human rights, as that term is currently understood, since all conceptions of rights if, indeed, there are any conceptions of rights, are completely determined and mediated by the culture in which they originate. An analysis of both international human rights instruments and the practice of states suggests that neither absolute universality nor absolute relativity holds sway in the treatment of human rights.

Absolute universality cannot hold true, because the wide diversity of societies and cultures clearly interpret and apply the same rights in different ways. This is evidenced by the significant number of human rights instruments of both a legally binding and "soft law" [24] nature now in existence. Lying somewhere between the two absolutes is a middle way which reconciles the demands of universality and the demands of culture. Before it is possible to analyse where this middle way might lie, it is necessary to examine further some of the basic terms and concepts upon which this discussion is based.

First, it is necessary to look more closely at the nature of human rights in the international system. Second, some attempt must be made to determine the methods by which states give effect to these human rights and to examine the roles which states and international human rights bodies play in the mediation of the principles of universality and cultural relativity.

Historical development

Finally, it is essential to ask what is meant by culture and how culture relates to states and sub-state groupings. If one accepts that a human right is an entitlement which is owned by a right-owner, that is, an individual human being, then there must be a correlative duty on the part of the duty bearer, in this case the state, to respect that right unconditionally. To use Dworkin's terminology, a right is a "trump" to which all other considerations of social policy must yield. Furthermore, since human rights are inalienable they cannot legitimately be denied.

The human rights owned by individuals are set down in a number of instruments, some of which are legally binding and some of which are not. Without engaging in a doctrinal argument over the precise legal status of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, [27] it is probably fair to say that, at the very least, it represents a high degree of international consensus on those human rights which are owned by all members of the human race. It is also clear that the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is the progenitor of most contemporary human rights instruments. All the regional human rights conventions - the European, American and African Conventions - recognise this fact directly in their preambles, while the Vienna Declaration and Programme of Actions acknowledges that the Universal Declaration has been the basis for the UN's standard setting work, especially in its manifestation in the two International Covenants.

In the light of this it would seem difficult, if not impossible, to deny that the Universal Declaration is a more or less comprehensive catalogue of human rights. Although it is possible to claim this status for the Universal Declaration, it is doubtful whether this, in itself, is particularly helpful, since identification of the rights themselves does not reveal their content. It is all very well to know that one has the right to life, liberty and security of the person, but until it is possible to state with some specificity how this right will apply in concrete circumstances, it remains a fairly abstract proposition.

In this sense it is possible to view the rights set down in the Universal Declaration as a catalogue of moral entitlements having some pre-normative status rather than legal norms. While Donnelly takes the view that human rights are moral entitlements and that they are thus different to rights embodied as legal norms, that is, legal rights, [29] it is none the less possible to argue that the value of normative human rights is that they confer both a legitimacy on their status and establish a direct legal relationship between the individual and the state.

I would agree with Donnelly that appeal to moral entitlements is a particularly powerful device, but the power of legal legitimacy can provide a sharper tool if we wish both to protect and vindicate human rights when they are violated. In order to make human rights useful, therefore, it is necessary to move away from their indeterminacy and to concretise them. As noted above this requires the interpretation and application of a right in concrete circumstances.

It is only when an individual claims that his or her right has been violated and some authoritative decision making agency interprets and applies the right to the situation at hand that human rights norms begin to manifest their true scope and identity. This is not simply a matter of legal interpretation, it is also something much deeper than this. The vindication of a right will often reveal a deficiency in some social policy and the state will thus be required not only to make reparation to the victim, but to take appropriate steps to ensure that such a violation does not happen again.

In a sense, it involves some reconstruction of the apparatus of the state to ensure that it is in line with the state's human rights obligations.

As Ronald Dworkin has commented, "the process of making an abstract right successively more concrete is not simply a process of deduction or interpretation of the abstract statement but a fresh step in political theory. Although an individual is a right-owner, it is none the less the function of the state to take the necessary measures to ensure that the right is fully protected.

In so doing, the state enjoys a degree of latitude. Because states have different social institutions and traditions, there must be scope for different methods of implementing human rights. These can be widely divergent, but this does not mean that human rights are denied just because they are implemented differently. Take, for example, the right to a fair trial. While common law states might use an adversarial system and the civil law states an inquisitorial system, this does not mean that the right will be inadequately protected in either.

The extent to which human rights institutions are able to take local state variations into account in the implementation of human rights depends upon a number of factors. The most important of these is the constituent instrument under which a particular institution functions. Instead of caring for the family or community, people only care for their own rights.

But in countries like Canada where human rights are, for the most part, legally respected , citizens follow these laws because they do have a sense of community and care for each other. Yet others claim that as China and other non-democratic countries become more powerful, human rights will be less important internationally. It is true that such countries do work to undermine many human rights, at home and at the UN. But that makes human rights more relevant, not less. We all need protection against abusive governments.

This topic is difficult to discuss internationally, because some places, especially but not only Russia and countries in Africa and the Middle East, still have laws that prohibit homosexuality. Some religious groups, in the Western world as elsewhere, are also homophobic. Indigenous rights are collective rights. Indigenous ways of life, languages, religions, cultures and land bases are threatened. Canada voted against the Declaration, but later reversed its position. A collective right that affects everyone everywhere is the right to a clean and healthy environment.

This includes the right to protection against climate changes that undermine our livelihoods and well-being. Another collective right is the right to peace. Viewed narrowly, this is the right not to live in a state of war. In , many people still live in war-torn countries, especially countries in the Middle East and parts of Africa.

- Crumbling FoundationsDavid Smiley.

- Clean environment is a right.

- Signs of progress.

Others, in the Ukraine, live in fear of war. And we all live in fear of nuclear war. Both climate change and war create huge refugee populations.