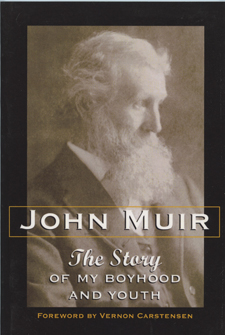

The Story of My Boyhood and Youth

Dec 29, Brandon rated it really liked it Shelves: This is a deeply charming book. John Muir's boyhood and youth took place in a world much different, and much wilder, than the biologically impoverished world of today. He had a whippoorwill singing on the post outside his home in Wisconsin and passenger pigeons arrived in droves in the springtime.

His observations of nature are oftentimes remarkable and show a keen attention to the natural world e. A very enj This is a deeply charming book. A very enjoyable book filled with many amazing tales and happenings. Muir's writing is beautiful but it is sad to read about the destruction of the Wisconsin wilderness by settlers. Muir's family moved from Scotland to Wisconsin in the 19th century to farm. He has great affection for all the wild animals and plants he encountered. He was a keen observer of the life around him.

Jun 15, Brooke rated it really liked it Shelves: I really enjoyed this book. What a likable person! His stories of his rambunctious youth made me smile and gave me hope for my boys.

See a Problem?

Sep 03, Drew rated it it was amazing. The most inspirational book I have read for a very long time. Muir could recite the New Testament in one sitting by memory when he was twelve and he had also memorized two-thirds of the Old Testament. He was the inspiration for the formation of Yellowstone National Park and the founder of the Sierra Club. He has had an extraordinary impact on each of us. Sep 04, Terry rated it really liked it. This book is remarkable in that, in simple yet beautiful prose, takes the reader to a place long gone A spiritually engaging book.

Jun 07, Pam rated it liked it Shelves: Oct 04, Rafelmenmell rated it liked it. La infancia era bastante salvaje en aquellos tiempos. Feb 10, Barry Cunningham rated it really liked it.

The Story of My Boyhood and Youth

Actually, the Project Gutenberg edition on Stanza on my iPhone. I read Muir's The Yosemite last year and found that book and him utterly amazing. Decided to read some more of his works, and this seemed like the logical place to start. His origins may not have been that unusual for his time, but where he went from there in his late youth and early manhood seem entirely unexpected. His early life and his narrative fall into three parts: In his early schooling in Scotland, corporal punishment was the chief pedagogical technique. Sort of an early form of standardized testing: This, and the savagery of the other boys in school, might have soured one on education forever.

Remarkably, in Muir's case, they did not.

The Story of My Boyhood and Youth by John Muir

Even in the narrative of his early youth, he describes his explorations of nature: Suddenly, in , when Muir was about eleven, his father decided the family would emigrate to America. First, his father and the three eldest children, made the crossing and found some land in Wisconsin. They built a shanty and set about the hard work of making a farm out of the wilderness.

By fall, they had cleared the land and built a frame house so that the rest of the family was able to join them. But despite the hard labor that this entailed, his description of this time is one of overwhelming joy as he and his brother Daniel enjoy the freedom of the wilderness and discover the animals of the woods and the farm. This part of his narrative contains vivid descriptions of his discovery of nature around him. After eight years, having already built a comfortable farm, his father bought another half-section of land four or five miles distant, and again commenced the back-breaking work of clearing it and building it up.

Remarkably, for all the strenuous work he was doing and his father's strict religious discouragement, Muir set about trying to educate himself in what little time he had available outside of work. He got his father to buy him a book on arithmetic, and despite not having attended school since the age of 11, he was able to work through it in short order. He then set about trying to read all that he could, borrowing or acquiring books as he could.

All this was sternly opposed by his father, who believed that the Bible was the only book he needed. Muir would try to steal five to ten minutes to read by candlelight around 8pm before his father would admonish him to put out the light and go to bed to be ready for work tomorrow. One night, his father made the tactical mistake of telling him that he shouldn't have to be scolded every night into putting out the light, but that he could get up as early as he liked.

Immediately, Muir began going to bed with the rest of the family, but getting up at 1 AM to work on his inventions. He built scientific instruments and whittled clocks of his own design. Later, when he showed them to a knowledgeable neighbor, he was told he should go exhibit them at the State Fair, and that he could easily secure a job in a machine shop. Eventually, this is just what he did. When he left home for the State Fair, his father assured him that he was on his own and if he should run into a rough spell, he shouldn't look to his father for help. At the State Fair, he was offered a job in a machine shop.

After a few months though, it did really work out. There wasn't enough work or instruction available to satisfy him. So he moved to Madison. After a little while he figured out that he could get into the University of Wisconsin, teaching himself enough to keep up with the rest of the students, and earn enough doing odd jobs to put himself through college. So that's just what he did, learning a great variety of things befitting his wonderous curiousity: He wrote more books about later. Sep 27, Lartemis added it Shelves: Honestly, I only dabbled in this as there was no audio book available.

My book club's discussion was fascinating. Only one of 18 people didn't like the book. Everyone else loved it. I love it when I find a book to look forward to reading at bedtime every night and this was one of those!

John Muir's first book and a memoir of his childhood in Scotland growing up in the country under a brutally strict father who used the Christian faith as a rod. The early intelligence of Muir is evident as he discusses the educational methods of Scottish fathers to beat learning into the children. His love of nature is early evident and inspiring in his words of observation of the wildlife a I love it when I find a book to look forward to reading at bedtime every night and this was one of those! His love of nature is early evident and inspiring in his words of observation of the wildlife around him.

His father brings John and his brother and sister to America to the Wisconsin backwoods to start a farmstead and build a house for his mother and other siblings who will follow. His descriptions of the lush wilderness of Wisconsin which is no more, is wonderful reading.

His father abuses him with an unbearable workload until he is ready to leave home. It is heartbreaking to read the toil he puts into the parents farm and the paltry sum he has in his pocket when he is ready to leave. Part of the money he raises from inventions of timepieces and a thermometer and other wooden machines before he leaves home.

His inventions attract many people and the kindness of the citizens he encounters is amazing! He arrives at his destination, the U. Muir is a natural writer of botany and the wilderness around him as well as the social systems he lives in, from family to neighbors to new friends and university society. He obviously has a deep, thoughtful gift of observation that is guided along scientific reason which propels him through the world. This book should be the starting point of John Muir reading and it is a compelling story of California's premier environmentalist, John Muir!

Sep 02, Ben rated it it was amazing Recommends it for: Recommended to Ben by: Sequoia National Forest giftshop. John Muir founded the Sierra Club. The Sierra Club headquarters is on the 2nd floor of the building I work in 85 Second Street , so I get to see all of their published books whenever someone too lazy to walk to the second floor gets on the elevator.

Sometimes, when I walk up to the 7th, I hope to see someone there to talk to them about other books like this. It was a recollection of his youth back to 5 or 6 years old in John Muir founded the Sierra Club. It was a recollection of his youth back to 5 or 6 years old in Scotland. His father moved him and his second oldest brother to Wisconsin when he was 11 to start a farm.

These stories follow Muir's life like any coming of age book, but written with only the important details: The most interesting parts for me were his creative approach to all challenges. The way he looked at problems differently than his father and neighbors. This book could be considered a scrapbook of accomplishments: John Muir was an amazing person even before he started exploring California's mountains and wilderness. I had a lot of mixed feelings about things in my own life based on how they are described in this book.

Perhaps it was the right time in my life to read about this stuff, but I think anyone could get enjoyment out of it. Aug 28, Meghan Fidler rated it really liked it Shelves: John Muir was one of the first influential environmentalists in the United States. We owe his acts of diligence for the pleasures we see at many parks, like Yosemite Valley and Sequoia National Park.

This memoir is another one of the pleasures found in the world that is due to John Muir. Beginning with a description of his childhood in Scotland, Muir goes on to describe the wealth that was the wilderness in Wisconsin. He is frank about the workload and frank about the nature of life and death on John Muir was one of the first influential environmentalists in the United States.

He is frank about the workload and frank about the nature of life and death on the farm. Throughout the book there are little moments when Muir seems to stop speaking about his story, and start speaking the story of humanity. I quote the following passage as an example, and enticement for future readers, of such an observation. Fortunately many are too small to be seen, and therefore enjoy a life beyond our reach.

Nov 15, Dana rated it really liked it Shelves: I read this several years ago and came across a little bit about Muir exploring the Amazon in the book I'm currently reading, "The River of Doubt. The story I most remember is about the passenger pigeons. I found that this book is part of The Project Gutenberg" and found where he talks about these incredible birds and the human acts that led to their extinction. Not less exciting and memorable was Audubon's wonde I read this several years ago and came across a little bit about Muir exploring the Amazon in the book I'm currently reading, "The River of Doubt.

Not less exciting and memorable was Audubon's wonderful story of the passenger pigeon, a beautiful bird flying in vast flocks that darkened the sky like clouds, countless millions assembling to rest and sleep and rear their young in certain forests, miles in length and breadth, fifty or a hundred nests on a single tree; the overloaded branches bending low and often breaking; the farmers gathering from far and near, beating down countless thousands of the young and old birds from their nests and roosts with long poles at night, and in the morning driving their bands of hogs, some of them brought from farms a hundred miles distant, to fatten on the dead and wounded covering the ground.

Jun 29, Ms. Ewing rated it it was amazing Shelves: John Muir is familiar to me as an old-time conservationist and old man wandering in the woods. But this is what he wrote about his childhood growing up in Scotland and Wisconsin during the pioneer days. I really enjoyed it. It had a touch of the "Little House on the Prairie" with all the interesting descriptions of everyday life.

His father was a real jerk and made him dig a well by chipping through stone for 17 hours a day with poison gas, among other things. But the coolest thing that I didn' John Muir is familiar to me as an old-time conservationist and old man wandering in the woods. But the coolest thing that I didn't know about him is that he was an inventor and used to steal secret moments away from the farm work when his father wasn't watching him because apparently inventing was not approved in the Bible and whittle clockwork pieces out of wood for his inventions.

He invented things like a bed that would set you on your feet in the morning and a desk that would put the proper book out for you to study at each hour of the day. Why don't we have these things today? This was a very cool biography. There are no discussion topics on this book yet.

John Muir — was a Scottish-American naturalist, author, and early advocate of preservation of wilderness in the United States. His letters, essays, and books telling of his adventures in nature, especially in the Sierra Nevada mountains of California, have been read by millions. His activism helped to preserve the Yosemite Valley, Sequoia National Park and other wilderness areas. The S John Muir — was a Scottish-American naturalist, author, and early advocate of preservation of wilderness in the United States.

The Sierra Club, which he founded, is now one of the most important conservation organizations in the United States. One of the best-known hiking trails in the U. In his later life, Muir devoted most of his time to the preservation of the Western forests. He petitioned the U. The spiritual quality and enthusiasm toward nature expressed in his writings inspired readers, including presidents and congressmen, to take action to help preserve large nature areas. He is today referred to as the "Father of the National Parks" and the National Park Service has produced a short documentary about his life.

Muir's biographer, Steven J. Holmes, believes that Muir has become "one of the patron saints of twentieth-century American environmental activity," both political and recreational. As a result, his writings are commonly discussed in books and journals, and he is often quoted by nature photographers such as Ansel Adams. I was screaming, of course, but as soon as I was imprisoned the fear of being kicked quenched all noise. I hardly dared breathe.

My only hope was in motionless silence. Imagine the agony I endured! I did not steal any more of his flowers. He was a good hard judge of boy nature. I was in Peter's hands some time before this, when I was about two and a half years old. The servant girl bathed us small folk before putting us to bed. The smarting soapy scrubbings of the Saturday nights in preparation for the Sabbath were particularly severe, and we all dreaded them. My sister Sarah, the next older than me, wanted the long-legged stool I was sitting on awaiting my turn, so she just tipped me off.

My chin struck on the edge of the bath-tub, and, as I was talking at the time, my tongue happened to be in the way of my teeth when they were closed by the blow, and a deep gash was cut on the side of it, which bled profusely. Mother came running at the noise I made, wrapped me up, put me in the servant girl's arms and told her to run with me through the garden and out by a back way to Peter Lawson to have something done to stop the bleeding.

He simply pushed a wad of cotton into my mouth after soaking it in some brown astringent stuff, and told me to be sure to keep my mouth shut and all would soon be well. Mother put me to bed, calmed my fears, and told me to lie still and sleep like a gude bairn. But just as I was dropping off to sleep I swallowed the bulky wad of medicated cotton and with it, as I imagined, my tongue also. My screams over so great a loss brought mother, darkest corners of the house, and oftentimes a long search was required to find me.

But after we were a few years older, we enjoyed bathing with other boys as we wandered along the shore, careful, however, not to get into a pool that had an invisible boy-devouring monster at the bottom of it. Such pools, miniature maelstroms, were called "sookin-in-goats" and were well known to most of us. Nevertheless we never ventured into any pool on strange parts of the coast before we had thrust a stick into it. If the stick were not pulled out of our hands, we boldly entered and enjoyed plashing and ducking long ere we had learned to swim. One of our best playgrounds was the famous old Dunbar Castle, to which King Edward fled after his defeat at Bannockburn.

It was built more than a thousand years ago, and though we knew little of its history, we had heard many mysterious stories of the battles fought about its walls, and firmly believed that every bone we found in the ruins belonged to an ancient warrior. We tried to see who could climb highest on the crumbling peaks and crags, and took chances that no cautious mountaineer would try. That I did not fall and finish my rock-scrambling in those adventurous boyhood days seems now a reasonable wonder.

Among our best games were running, jumping, wrestling, and scrambling. I was so proud of my skill as a climber that when I first heard of hell from a servant girl who loved to tell its horrors and warn us that if we did anything wrong we would be cast into it, I always insisted that I could climb out of it. I imagined it was only a sooty pit with stone walls like those of the castle, and I felt sure there must be chinks and cracks in the masonry for fingers and toes.

Anyhow the terrors of the horrible place seldom lasted long beyond the telling; for natural faith casts out fear. Most of the Scotch children believe in ghosts, and some under peculiar conditions continue to believe in them all through life. Grave ghosts are deemed particularly dangerous, and many of the most credulous will go far out of their way to avoid passing through or near a graveyard in the dark.

After being instructed by the servants in the nature, looks, and habits of the various black and white ghosts, boowuzzies, and witches we often speculated as to whether they could run fast, and tried to believe that we had a good chance to get away from most of them. To improve our speed and wind, we often took long runs into the country.

Tam o' Shanter's mare outran a lot of witches,--at least until she reached a place of safety beyond the keystone of the bridge,--and we thought perhaps we also might be able to outrun them. Our house formerly belonged to a physician, and a servant girl told us that the ghost of the dead doctor haunted one of the unoccupied rooms in the second story that was kept dark on account of a heavy window-tax.

Our bedroom was adjacent to the ghost room, which had in it a lot of chemical apparatus,--glass tubing, glass and brass retorts, test-tubes, flasks, etc. In the long summer days David and I were put to bed several hours before sunset. Mother tucked us in carefully, drew the curtains of the big old-fashioned bed, and told us to lie still and sleep like gude bairns; but we were usually out of bed, playing games of daring called "scootchers," about as soon as our loving mother reached the foot of the stairs, for we couldn't lie still, however hard we might try.

Going into the ghost room was regarded as a very great scootcher. After venturing in a few steps and rushing back in terror, I used to dare David to go as far without getting caught. The roof of our house, as well as the crags and walls of the old castle, offered fine mountaineering exercise.

Our bedroom was lighted by a dormer window. One night I opened it in search of good scootchers and hung myself out over the slates, holding on to the sill, while the wind was making a balloon of my nightgown. I then dared David to try the adventure, and he did. Then I went out again and hung by one hand, and David did the same.

Then I hung by one finger, being careful not to slip, and he did that too. Then I stood on the sill and examined the edge of the left wall of the window, crept up the slates along its side by slight finger-holds, got astride of the roof, sat there a few minutes looking at the scenery over the garden wall while the wind was howling and threatening to blow me off, then managed to slip down, catch hold of the sill, and get safely back into the room.

But before attempting this scootcher, recognizing its dangerous character, with commendable caution I warned David that in case I should happen to slip I would grip the rain-trough when I was going over the eaves and hang on, and that he must then run fast downstairs and tell father to get a ladder for me, and tell him to be quick because I would soon be tired hanging dangling in the wind by my hands. After my return from this capital scootcher, David, not to be outdone, crawled up to the top of the window-roof, and got bravely astride of it; but in trying to return he lost courage and began to greet to cry , "I canna get doon.

Oh, I canna get doon. If you greet, fayther will hear, and gee us baith an awfu' skelping. This finished scootcher-scrambling for the night and frightened us into bed. In the short winter days, when it was dark even at our early bedtime, we usually spent the hours before going to sleep playing voyages around the world under the bed-clothing. After mother had carefully covered us, bade us good-night and gone downstairs, we set out on our travels.

Burrowing like moles, we visited France, India, America, Australia, New Zealand, and all the places we had ever heard of; our travels never ending until we fell asleep. When mother came to take a last look at us, before she went to bed, to see that we were covered, we were oftentimes covered so well that she had difficulty in finding us, for we were hidden in all sorts of positions where sleep happened to overtake us, but in the morning we always found ourselves in good order, lying straight like gude bairns, as she said.

Some fifty years later, when I visited Scotland, I got one of my Dunbar schoolmates to introduce me to the owners of our old home, from whom I obtained permission to go upstairs to examine our bedroom window and judge what sort of adventure getting on its roof must have been, and with all my after experience in mountaineering, I found that what I had done in daring boyhood was now beyond my skill. Boys are often at once cruel and merciful, thoughtlessly hard-hearted and tender-hearted, sympathetic, pitiful, and kind in ever changing contrasts.

Love of neighbors, human or animal, grows up amid savage traits, coarse and fine. When father made out to get us securely locked up in the back yard to prevent our shore and field wanderings, we had to play away the comparatively dull time as best we could. One of our amusements was hunting cats without seriously hurting them. These sagacious animals knew, however, that, though not very dangerous, boys were not to be trusted. One time in particular I remember, when we began throwing stones at an experienced old Tom, not wishing to hurt him much, though he was a tempting mark.

He soon saw what we were up to, fled to the stable, and climbed to the top of the hay manger. He was still within range, however, and we kept the stones flying faster and faster, but he just blinked and played possum without wincing either at our best shots or at the noise we made. I happened to strike him pretty hard with a good-sized pebble, but he still blinked and sat still as if without feeling.

All took heartily to this sort of cat mercy and began throwing the heaviest stones we could manage, but that old fellow knew what characters we were, and just as we imagined him mercifully dead he evidently thought the play was becoming too serious and that it was time to retreat; for suddenly with a wild whirr and gurr of energy he launched himself over our heads, rushed across the yard in a blur of speed, climbed to the roof of another building and over the garden wall, out of pain and bad company, with all his lives wideawake and in good working order.

After we had thus learned that Tom had at least nine lives, we tried to verify the common saying that no matter how far cats fell they always landed on their feet unhurt. We caught one in our back yard, not Tom but a smaller one of manageable size, and somehow got him smuggled up to the top story of the house. I don't know how in the world we managed to let go of him, for as soon as we opened the window and held him over the sill he knew his danger and made violent efforts to scratch and bite his way back into the room; but we determined to carry the thing through, and at last managed to drop him.

I can remember to this day how the poor creature in danger of his life strained and balanced as he was falling and managed to alight on his feet. This was a cruel thing for even wild boys to do, and we never tried the experiment again, for we sincerely pitied the poor fellow when we saw him creeping slowly away, stunned and frightened, with a swollen black and blue chin. Again--showing the natural savagery of boys--we delighted in dog-fights, and even in the horrid red work of slaughter-houses, often running long distances and climbing over walls and roofs to see a pig killed, as soon as we heard the desperately earnest squealing.

And if the butcher was good-natured, we begged him to let us get a near view of the mysterious insides and to give us a bladder to blow up for a foot-ball. But here is an illustration of the better side of boy nature. In our back yard there were three elm trees and in the one nearest the house a pair of robin-redbreasts had their nest. When the young were almost able to fly, a troop of the celebrated "Scottish Grays," visited Dunbar, and three or four of the fine horses were lodged in our stable.

When the soldiers were polishing their swords and helmets, they happened to notice the nest, and just as they were leaving, one of them climbed the tree and robbed it. With sore sympathy we watched the young birds as the hard-hearted robber pushed them one by one beneath his jacket,--all but two that jumped out of the nest and tried to fly, but they were easily caught as they fluttered on the ground, and were hidden away with the rest.

The distress of the bereaved parents, as they hovered and screamed over the frightened crying children they so long had loved and sheltered and fed, was pitiful to see; but the shining soldier rode grandly away on his big gray horse, caring only for the few pennies the young songbirds would bring and the beer they would buy, while we all, sisters and brothers, were crying and sobbing. I remember, as if it happened this day, how my heart fairly ached and choked me. Mother put us to bed and tried to comfort us, telling us that the little birds would be well fed and grow big, and soon learn to sing in pretty cages; but again and again we rehearsed the sad story of the poor bereaved birds and their frightened children, and could not be comforted.

Father came into the room when we were half asleep and still sobbing, and I heard mother telling him that, "a' the bairns' hearts were broken over the robbing of the nest in the elm. After attaining the manly, belligerent age of five or six years, very few of my schooldays passed without a fist fight, and half a dozen was no uncommon number. When any classmate of our own age questioned our rank and standing as fighters, we always made haste to settle the matter at a quiet place on the Davel Brae.

To be a "gude fechter" was our highest ambition, our dearest aim in life in or out of school. To be a good scholar was a secondary consideration, though we tried hard to hold high places in our classes and gloried in being Dux.

The Story of My Boyhood and Youth by John Muir

We fairly reveled in the battle stories of glorious William Wallace and Robert the Bruce, with which every breath of Scotch air is saturated, and of course we were all going to be soldiers. On the Davel Brae battleground we often managed to bring on something like real war, greatly more exciting than personal combat. Choosing leaders, we divided into two armies. In winter damp snow furnished plenty of ammunition to make the thing serious, and in summer sand and grass sods.

Cheering and shouting some battle-cry such as "Bannockburn! The Last War in India! For heavy battery work we stuffed our Scotch blue bonnets with snow and sand, sometimes mixed with gravel, and fired them at each other as cannon-balls. Of course we always looked eagerly forward to vacation days and thought them slow in coming. Old Mungo Siddons gave us a lot of gooseberries or currants and wished us a happy time.

Some sort of special closing-exercises--singing, recitations, etc. An exciting time came when at the age of seven or eight years I left the auld Davel Brae school for the grammar school. Of course I had a terrible lot of fighting to do, because a new scholar had to meet every one of his age who dared to challenge him, this being the common introduction to a new school. It was very strenuous for the first month or so, establishing my fighting rank, taking up new studies, especially Latin and French, getting acquainted with new classmates and the master and his rules.

In the first few Latin and French lessons the new teacher, Mr. Lyon, blandly smiled at our comical blunders, but pedagogical weather of the severest kind quickly set in, when for every mistake, everything short of perfection, the taws was promptly applied. We had to get three lessons every day in Latin, three in French, and as many in English, besides spelling, history, arithmetic, and geography.

Word lessons in particular, the wouldst-couldst-shouldst-have-loved kind, were kept up, with much warlike thrashing, until I had committed the whole of the French, Latin, and English grammars to memory, and in connection with reading-lessons we were called on to recite parts of them with the rules over and over again, as if all the regular and irregular incomprehensible verb stuff was poetry. In addition to all this, father made me learn so many Bible verses every day that by the time I was eleven years of age I had about three fourths of the Old Testament and all of the New by heart and by sore flesh.

I could recite the New Testament from the beginning of Matthew to the end of Revelation without a single stop. The dangers of cramming and of making scholars study at home instead of letting their little brains rest were never heard of in those days. We carried our school-books home in a strap every night and committed to memory our next day's lessons before we went to bed, and to do that we had to bend our attention as closely on our tasks as lawyers on great million-dollar cases. I can't conceive of anything that would now enable me to concentrate my attention more fully than when I was a mere stripling boy, and it was all done by whipping,--thrashing in general.

Old-fashioned Scotch teachers spent no time in seeking short roads to knowledge, or in trying any of the new-fangled psychological methods so much in vogue nowadays. There was nothing said about making the seats easy or the lessons easy. We were simply driven pointblank against our books like soldiers against the enemy, and sternly ordered, "Up and at 'em. Commit your lessons to memory! Fighting was carried on still more vigorously in the high school than in the common school.

Whenever any one was challenged, either the challenge was allowed or it was decided by a battle on the seashore, where with stubborn enthusiasm we battered each other as if we had not been sufficiently battered by the teacher. When we were so fortunate as to finish a fight without getting a black eye, we usually escaped a thrashing at home and another next morning at school, for other traces of the fray could be easily washed off at a well on the church brae, or concealed, or passed as results of playground accidents; but a black eye could never be explained away from downright fighting.

A good double thrashing was the inevitable penalty, but all without avail; fighting went on without the slightest abatement, like natural storms; for no punishment less than death could quench the ancient inherited belligerence burning in our pagan blood. Nor could we be made to believe it was fair that father and teacher should thrash us so industriously for our good, while begrudging us the pleasure of thrashing each other for our good. All these various thrashings, however, were admirably influential in developing not only memory but fortitude as well.

For if we did not endure our school punishments and fighting pains without flinching and making faces, we were mocked on the playground, and public opinion on a Scotch playground was a powerful agent in controlling behavior; therefore we at length managed to keep our features in smooth repose while enduring pain that would try anybody but an American Indian. Far from feeling that we were called on to endure too much pain, one of our playground games was thrashing each other with whips about two feet long made from the tough, wiry stems of a species of polygonum fastened together in a stiff, firm braid.

One of us handing two of these whips to a companion to take his choice, we stood up close together and thrashed each other on the legs until one succumbed to the intolerable pain and thus lost the game. Nearly all of our playground games were strenuous,--shin-battering shinny, wrestling, prisoners' base, and dogs and hares,--all augmenting in no slight degree our lessons in fortitude. Moreover, we regarded our punishments and pains of every sort as training for war, since we were all going to be soldiers. Besides single combats we sometimes assembled on Saturdays to meet the scholars of another school, and very little was required for the growth of strained relations, and war.

The immediate cause might be nothing more than a saucy stare. Perhaps the scholar stared at would insolently inquire, "What are ye glowerin' at, Bob? This opened the battle, and every good scholar belonging to either school was drawn into it. After both sides were sore and weary, a strong-lunged warrior would be heard above the din of battle shouting, "I'll tell ye what we'll dae wi' ye. If ye'll let us alane we'll let ye alane! Notwithstanding the great number of harshly enforced rules, not very good order was kept in school in my time.

There were two schools within a few rods of each other, one for mathematics, navigation, etc. The masters lived in a big freestone house within eight or ten yards of the schools, so that they could easily step out for anything they wanted or send one of the scholars. The moment our master disappeared, perhaps for a book or a drink, every scholar left his seat and his lessons, jumped on top of the benches and desks or crawled beneath them, tugging, rolling, wrestling, accomplishing in a minute a depth of disorder and din unbelievable save by a Scottish scholar.

We even carried on war, class against class, in those wild, precious minutes. A watcher gave the alarm when the master opened his house-door to return, and it was a great feat to get into our places before he entered, adorned in awful majestic authority, shouting "Silence! Forty-seven years after leaving this fighting school, I returned on a visit to Scotland, and a cousin in Dunbar introduced me to a minister who was acquainted with the history of the school, and obtained for me an invitation to dine with the new master.

Of course I gladly accepted, for I wanted to see the old place of fun and pain, and the battleground on the sands. Lyon, our able teacher and thrasher, I learned, had held his place as master of the school for twenty or thirty years after I left it, and had recently died in London, after preparing many young men for the English Universities.

At the dinner-table, while I was recalling the amusements and fights of my old schooldays, the minister remarked to the new master, "Now, don't you wish that you had been teacher in those days, and gained the honor of walloping John Muir? The old freestone school building was still perfectly sound, but the carved, ink-stained desks were almost whittled away. The highest part of our playground back of the school commanded a view of the sea, and we loved to watch the passing ships and, judging by their rigging, make guesses as to the ports they had sailed from, those to which they were bound, what they were loaded with, their tonnage, etc.

In stormy weather they were all smothered in clouds and spray, and showers of salt scud torn from the tops of the waves came flying over the playground wall. In those tremendous storms many a brave ship foundered or was tossed and smashed on the rocky shore. When a wreck occurred within a mile or two of the town, we often managed by running fast to reach it and pick up some of the spoils. In particular I remember visiting the battered fragments of an unfortunate brig or schooner that had been loaded with apples, and finding fine unpitiful sport in rushing into the spent waves and picking up the red-cheeked fruit from the frothy, seething foam.

All our school-books were extravagantly illustrated with drawings of every kind of sailing-vessel, and every boy owned some sort of craft whittled from a block of wood and trimmed with infinite pains,--sloops, schooners, brigs, and full-rigged ships, with their sails and string ropes properly adjusted and named for us by some old sailor. These precious toy craft with lead keels we learned to sail on a pond near the town. With the sails set at the proper angle to the wind, they made fast straight voyages across the pond to boys on the other side, who readjusted the sails and started them back on the return voyages.

Oftentimes fleets of half a dozen or more were started together in exciting races. Our most exciting sport, however, was playing with gunpowder. We made guns out of gas-pipe, mounted them on sticks of any shape, clubbed our pennies together for powder, gleaned pieces of lead here and there and cut them into slugs, and, while one aimed, another applied a match to the touch-hole. With these awful weapons we wandered along the beach and fired at the gulls and solan-geese as they passed us. Fortunately we never hurt any of them that we knew of. We also dug holes in the ground, put in a handful or two of powder, tamped it well around a fuse made of a wheat-stalk, and, reaching cautiously forward, touched a match to the straw.

This we called making earthquakes. Oftentimes we went home with singed hair and faces well peppered with powder-grains that could not be washed out. Then, of course, came a correspondingly severe punishment from both father and teacher. Another favorite sport was climbing trees and scaling garden-walls. Boys eight or ten years of age could get over almost any wall by standing on each other's shoulders, thus making living ladders.

To make walls secure against marauders, many of them were finished on top with broken bottles imbedded in lime, leaving the cutting edges sticking up; but with bunches of grass and weeds we could sit or stand in comfort on top of the jaggedest of them. Like squirrels that begin to eat nuts before they are ripe, we began to eat apples about as soon as they were formed, causing, of course, desperate gastric disturbances to be cured by castor oil. Serious were the risks we ran in climbing and squeezing through hedges, and, of course, among the country folk we were far from welcome.

Farmers passing us on the roads often shouted by way of greeting: Back to the toon wi' ye. Gang back where ye belang. You're up to mischief, Ise warrant. I can see it. The gamekeeper'll catch ye, and maist like ye'll a' be hanged some day. Breakfast in those auld-lang-syne days was simple oatmeal porridge, usually with a little milk or treacle, served in wooden dishes called "luggies," formed of staves hooped together like miniature tubs about four or five inches in diameter.

One of the staves, the lug or ear, a few inches longer than the others, served as a handle, while the number of luggies ranged in a row on a dresser indicated the size of the family.

- Good Governance for Digital Policies: How to Get the Most Out of ICT: The Case of Spains Plan Avanza.

- The Story of My Boyhood and Youth.

- The Story of My Boyhood and Youth by John Muir - Free Ebook.

We never dreamed of anything to come after the porridge, or of asking for more. Our portions were consumed in about a couple of minutes; then off to school. At noon we came racing home ravenously hungry. The midday meal, called dinner, was usually vegetable broth, a small piece of boiled mutton, and barley-meal scone. None of us liked the barley scone bread, therefore we got all we wanted of it, and in desperation had to eat it, for we were always hungry, about as hungry after as before meals.

The evening meal was called "tea" and was served on our return from school.

- The story of my boyhood and youth.

- Meeting Dennis Wilson: Book Four.

- The Story of My Boyhood and Youth - Wikisource, the free online library.

It consisted, as far as we children were concerned, of half a slice of white bread without butter, barley scone, and warm water with a little milk and sugar in it, a beverage called "content," which warmed but neither cheered nor inebriated. Immediately after tea we ran across the street with our books to Grandfather Gilrye, who took pleasure in seeing us and hearing us recite our next day's lessons.

Then back home to supper, usually a boiled potato and piece of barley scone. Then family worship, and to bed. Our amusements on Saturday afternoons and vacations depended mostly on getting away from home into the country, especially in the spring when the birds were calling loudest. Father sternly forbade David and me from playing truant in the fields with plundering wanderers like ourselves, fearing we might go on from bad to worse, get hurt in climbing over walls, caught by gamekeepers, or lost by falling over a cliff into the sea.

Nevertheless, like devout martyrs of wildness, we stole away to the seashore or the green, sunny fields with almost religious regularity, taking advantage of opportunities when father was very busy, to join our companions, oftenest to hear the birds sing and hunt their nests, glorying in the number we had discovered and called our own.

A sample of our nest chatter was something like this: Willie Chisholm would proudly exclaim--"I ken know seventeen nests, and you, Johnnie, ken only fifteen. You ken only three o' the best singers. Maist of yours are only sparrows and linties and robin-redbreasts.

Then perhaps Bob Richardson would loudly declare that he "kenned mair nests than onybody, for he kenned twenty-three, with about fifty eggs in them and mair than fifty young birds--maybe a hundred. Some of them naething but raw gorblings but lots of them as big as their mithers and ready to flee. And aboot fifty craw's nests and three fox dens. Ma father let me gang to a fox hunt, and man, it was grand to see the hounds and the lang-legged horses lowpin the dykes and burns and hedges! The nests, I fear, with the beautiful eggs and young birds, were prized quite as highly as the songs of the glad parents, but no Scotch boy that I know of ever failed to listen with enthusiasm to the songs of the skylarks.

Oftentimes on a broad meadow near Dunbar we stood for hours enjoying their marvelous singing and soaring. From the grass where the nest was hidden the male would suddenly rise, as straight as if shot up, to a height of perhaps thirty or forty feet, and, sustaining himself with rapid wing-beats, pour down the most delicious melody, sweet and clear and strong, overflowing all bounds, then suddenly he would soar higher again and again, ever higher and higher, soaring and singing until lost to sight even on perfectly clear days, and oftentimes in cloudy weather "far in the downy cloud," as the poet says.

To test our eyes we often watched a lark until he seemed a faint speck in the sky and finally passed beyond the keenest-sighted of us all. And finally only one of us would be left to claim that he still saw him. At last he, too, would have to admit that the singer had soared beyond his sight, and still the music came pouring down to us in glorious profusion, from a height far above our vision, requiring marvelous power of wing and marvelous power of voice, for that rich, delicious, soft, and yet clear music was distinctly heard long after the bird was out of sight.

Then, suddenly ceasing, the glorious singer would appear, falling like a bolt straight down to his nest, where his mate was sitting on the eggs. It was far too common a practice among us to carry off a young lark just before it could fly, place it in a cage, and fondly, laboriously feed it.

Sometimes we succeeded in keeping one alive for a year or two, and when awakened by the spring weather it was pitiful to see the quivering imprisoned soarer of the heavens rapidly beating its wings and singing as though it were flying and hovering in the air like its parents. To keep it in health we were taught that we must supply it with a sod of grass the size of the bottom of the cage, to make the poor bird feel as though it were at home on its native meadow,--a meadow perhaps a foot or at most two feet square.

Again and again it would try to hover over that miniature meadow from its miniature sky just underneath the top of the cage. At last, conscience-stricken, we carried the beloved prisoner to the meadow west of Dunbar where it was born, and, blessing its sweet heart, bravely set it free, and our exceeding great reward was to see it fly and sing in the sky. In the winter, when there was but little doing in the fields, we organized running-matches. A dozen or so of us would start out on races that were simply tests of endurance, running on and on along a public road over the breezy hills like hounds, without stopping or getting tired.

The only serious trouble we ever felt in these long races was an occasional stitch in our sides. One of the boys started the story that sucking raw eggs was a sure cure for the stitches. We had hens in our back yard, and on the next Saturday we managed to swallow a couple of eggs apiece, a disgusting job, but we would do almost anything to mend our speed, and as soon as we could get away after taking the cure we set out on a ten or twenty mile run to prove its worth. We thought nothing of running right ahead ten or a dozen miles before turning back; for we knew nothing about taking time by the sun, and none of us had a watch in those days.

Indeed, we never cared about time until it began to get dark. Then we thought of home and the thrashing that awaited us. Late or early, the thrashing was sure, unless father happened to be away. If he was expected to return soon, mother made haste to get us to bed before his arrival. We escaped the thrashing next morning, for father never felt like thrashing us in cold blood on the calm holy Sabbath. But no punishment, however sure and severe, was of any avail against the attraction of the fields and woods. It had other uses, developing memory, etc.

Wildness was ever sounding in our ears, and Nature saw to it that besides school lessons and church lessons some of her own lessons should be learned, perhaps with a view to the time when we should be called to wander in wildness to our heart's content.

Oh, the blessed enchantment of those Saturday runaways in the prime of the spring! How our young wondering eyes reveled in the sunny, breezy glory of the hills and the sky, every particle of us thrilling and tingling with the bees and glad birds and glad streams! Kings may be blessed; we were glorious, we were free,--school cares and scoldings, heart thrashings and flesh thrashings alike, were forgotten in the fullness of Nature's glad wildness. These were my first excursions,--the beginnings of lifelong wanderings.

Our grammar-school reader, called, I think, "Maccoulough's Course of Reading," contained a few natural-history sketches that excited me very much and left a deep impression, especially a fine description of the fish hawk and the bald eagle by the Scotch ornithologist Wilson, who had the good fortune to wander for years in the American woods while the country was yet mostly wild.

I read his description over and over again, till I got the vivid picture he drew by heart,--the long-winged hawk circling over the heaving waves, every motion watched by the eagle perched on the top of a crag or dead tree; the fish hawk poising for a moment to take aim at a fish and plunging under the water; the eagle with kindling eye spreading his wings ready for instant flight in case the attack should prove successful; the hawk emerging with a struggling fish in his talons, and proud flight; the eagle launching himself in pursuit; the wonderful wing-work in the sky, the fish hawk, though encumbered with his prey, circling higher, higher, striving hard to keep above the robber eagle; the eagle at length soaring above him, compelling him with a cry of despair to drop his hard-won prey; then the eagle steadying himself for a moment to take aim, descending swift as a lightning-bolt, and seizing the falling fish before it reached the sea.

Not less exciting and memorable was Audubon's wonderful story of the passenger pigeon, a beautiful bird flying in vast flocks that darkened the sky like clouds, countless millions assembling to rest and sleep and rear their young in certain forests, miles in length and breadth, fifty or a hundred nests on a single tree; the overloaded branches bending low and often breaking; the farmers gathering from far and near, beating down countless thousands of the young and old birds from their nests and roosts with long poles at night, and in the morning driving their bands of hogs, some of them brought from farms a hundred miles distant, to fatten on the dead and wounded covering the ground.

In another of our reading-lessons some of the American forests were described. The most interesting of the trees to us boys was the sugar maple, and soon after we had learned this sweet story we heard everybody talking about the discovery of gold in the same wonder-filled country. One night, when David and I were at grandfather's fireside solemnly learning our lessons as usual, my father came in with news, the most wonderful, most glorious, that wild boys ever heard. We were utterly, blindly glorious. After father left the room, grandfather gave David and me a gold coin apiece for a keepsake, and looked very serious, for he was about to be deserted in his lonely old age.

And when we in fullness of young joy spoke of what we were going to do, of the wonderful birds and their nests that we should find, the sugar and gold, etc. You'll find plenty hard, hard work. But nothing he could say could cloud our joy or abate the fire of youthful, hopeful, fearless adventure. Nor could we in the midst of such measureless excitement see or feel the shadows and sorrows of his darkening old age. To my schoolmates, met that night on the street, I shouted the glorious news, "I'm gan to Amaraka the morn! I said, "Weel, just you see if I am at the skule the morn!

Next morning we went by rail to Glasgow and thence joyfully sailed away from beloved Scotland, flying to our fortunes on the wings of the winds, care-free as thistle seeds. We could not then know what we were leaving, what we were to encounter in the New World, nor what our gains were likely to be. We were too young and full of hope for fear or regret, but not too young to look forward with eager enthusiasm to the wonderful schoolless bookless American wilderness. Even the natural heart-pain of parting from grandfather and grandmother Gilrye, who loved us so well, and from mother and sisters and brother was quickly quenched in young joy.

Father took with him only my sister Sarah thirteen years of age , myself eleven , and brother David nine , leaving my eldest sister, Margaret, and the three youngest of the family, Daniel, Mary, and Anna, with mother, to join us after a farm had been found in the wilderness and a comfortable house made to receive them. In crossing the Atlantic before the days of steamships, or even the American clippers, the voyages made in old-fashioned sailing-vessels were very long.

Ours was six weeks and three days. But because we had no lessons to get, that long voyage had not a dull moment for us boys. Father and sister Sarah, with most of the old folk, stayed below in rough weather, groaning in the miseries of seasickness, many of the passengers wishing they had never ventured in "the auld rockin' creel," as they called our bluff-bowed, wave-beating ship, and, when the weather was moderately calm, singing songs in the evenings,--"The Youthful Sailor Frank and Bold," "Oh, why left I my hame, why did I cross the deep," etc.

But no matter how much the old tub tossed about and battered the waves, we were on deck every day, not in the least seasick, watching the sailors at their rope-hauling and climbing work; joining in their songs, learning the names of the ropes and sails, and helping them as far as they would let us; playing games with other boys in calm weather when the deck was dry, and in stormy weather rejoicing in sympathy with the big curly-topped waves.

The captain occasionally called David and me into his cabin and asked us about our schools, handed us books to read, and seemed surprised to find that Scotch boys could read and pronounce English with perfect accent and knew so much Latin and French. In Scotch schools only pure English was taught, although not a word of English was spoken out of school. All through life, however well educated, the Scotch spoke Scotch among their own folk, except at times when unduly excited on the only two subjects on which Scotchmen get much excited, namely religion and politics.

So long as the controversy went on with fairly level temper, only gude braid Scots was used, but if one became angry, as was likely to happen, then he immediately began speaking severely correct English, while his antagonist, drawing himself up, would say: As we neared the shore of the great new land, with what eager wonder we watched the whales and dolphins and porpoises and seabirds, and made the good-natured sailors teach us their names and tell us stories about them! There were quite a large number of emigrants aboard, many of them newly married couples, and the advantages of the different parts of the New World they expected to settle in were often discussed.

My father started with the intention of going to the backwoods of Upper Canada. Before the end of the voyage, however, he was persuaded that the States offered superior advantages, especially Wisconsin and Michigan, where the land was said to be as good as in Canada and far more easily brought under cultivation; for in Canada the woods were so close and heavy that a man might wear out his life in getting a few acres cleared of trees and stumps. So he changed his mind and concluded to go to one of the Western States. On our wavering westward way a grain-dealer in Buffalo told father that most of the wheat he handled came from Wisconsin; and this influential information finally determined my father's choice.

At Milwaukee a farmer who had come in from the country near Fort Winnebago with a load of wheat agreed to haul us and our formidable load of stuff to a little town called Kingston for thirty dollars. On that hundred-mile journey, just after the spring thaw, the roads over the prairies were heavy and miry, causing no end of lamentation, for we often got stuck in the mud, and the poor farmer sadly declared that never, never again would he be tempted to try to haul such a cruel, heart-breaking, wagon-breaking, horse-killing load, no, not for a hundred dollars.

In leaving Scotland, father, like many other homeseekers, burdened himself with far too much luggage, as if all America were still a wilderness in which little or nothing could be bought. One of his big iron-bound boxes must have weighed about four hundred pounds, for it contained an old-fashioned beam-scales with a complete set of cast-iron counterweights, two of them fifty-six pounds each, a twenty-eight, and so on down to a single pound. Also a lot of iron wedges, carpenter's tools, and so forth, and at Buffalo, as if on the very edge of the wilderness, he gladly added to his burden a big cast-iron stove with pots and pans, provisions enough for a long siege, and a scythe and cumbersome cradle for cutting wheat, all of which he succeeded in landing in the primeval Wisconsin woods.

A land-agent at Kingston gave father a note to a farmer by the name of Alexander Gray, who lived on the border of the settled part of the country, knew the section-lines, and would probably help him to find a good place for a farm. So father went away to spy out the land, and in the mean time left us children in Kingston in a rented room.

It took us less than an hour to get acquainted with some of the boys in the village; we challenged them to wrestle, run races, climb trees, etc. When father returned he told us that he had found fine land for a farm in sunny open woods on the side of a lake, and that a team of three yoke of oxen with a big wagon was coming to haul us to Mr.

Gray's house, father again left us for a few days to build a shanty on the quarter-section he had selected four or five miles to the westward. In the mean while we enjoyed our freedom as usual, wandering in the fields and meadows, looking at the trees and flowers, snakes and birds and squirrels. With the help of the nearest neighbors the little shanty was built in less than a day after the rough bur-oak logs for the walls and the white-oak boards for the floor and roof were got together.

To this charming hut, in the sunny woods, overlooking a flowery glacier meadow and a lake rimmed with white water-lilies, we were hauled by an ox-team across trackless carex swamps and low rolling hills sparsely dotted with round-headed oaks. Just as we arrived at the shanty, before we had time to look at it or the scenery about it, David and I jumped down in a hurry off the load of household goods, for we had discovered a blue jay's nest, and in a minute or so we were up the tree beside it, feasting our eyes on the beautiful green eggs and beautiful birds,--our first memorable discovery.

The handsome birds had not seen Scotch boys before and made a desperate screaming as if we were robbers like themselves; though we left the eggs untouched, feeling that we were already beginning to get rich, and wondering how many more nests we should find in the grand sunny woods. Then we ran along the brow of the hill that the shanty stood on, and down to the meadow, searching the trees and grass tufts and bushes, and soon discovered a bluebird's and a woodpecker's nest, and began an acquaintance with the frogs and snakes and turtles in the creeks and springs.

This sudden plash into pure wildness--baptism in Nature's warm heart--how utterly happy it made us! Nature streaming into us, wooingly teaching her wonderful glowing lessons, so unlike the dismal grammar ashes and cinders so long thrashed into us. Here without knowing it we still were at school; every wild lesson a love lesson, not whipped but charmed into us.

Oh, that glorious Wisconsin wilderness! Everything new and pure in the very prime of the spring when Nature's pulses were beating highest and mysteriously keeping time with our own! Young hearts, young leaves, flowers, animals, the winds and the streams and the sparkling lake, all wildly, gladly rejoicing together!

Next morning, when we climbed to the precious jay nest to take another admiring look at the eggs, we found it empty. Not a shell-fragment was left, and we wondered how in the world the birds were able to carry off their thin-shelled eggs either in their bills or in their feet without breaking them, and how they could be kept warm while a new nest was being built. Well, I am still asking these questions. When I was on the Harriman Expedition I asked Robert Ridgway, the eminent ornithologist, how these sudden flittings were accomplished, and he frankly confessed that he didn't know, but guessed that jays and many other birds carried their eggs in their mouths; and when I objected that a jay's mouth seemed too small to hold its eggs, he replied that birds' mouths were larger than the narrowness of their bills indicated.

Then I asked him what he thought they did with the eggs while a new nest was being prepared. He didn't know; neither do I to this day. A specimen of the many puzzling problems presented to the naturalist. We soon found many more nests belonging to birds that were not half so suspicious. The handsome and notorious blue jay plunders the nests of other birds and of course he could not trust us. Almost all the others--brown thrushes, bluebirds, song sparrows, kingbirds, hen-hawks, nighthawks, whip-poor-wills, woodpeckers, etc.

We used to wonder how the woodpeckers could bore holes so perfectly round, true mathematical circles. We ourselves could not have done it even with gouges and chisels. We loved to watch them feeding their young, and wondered how they could glean food enough for so many clamorous, hungry, unsatisfiable babies, and how they managed to give each one its share; for after the young grew strong, one would get his head out of the door-hole and try to hold possession of it to meet the food-laden parents.

How hard they worked to support their families, especially the red-headed and speckledy woodpeckers and flickers; digging, hammering on scaly bark and decaying trunks and branches from dawn to dark, coming and going at intervals of a few minutes all the livelong day! We discovered a hen-hawk's nest on the top of a tall oak thirty or forty rods from the shanty and approached it cautiously. One of the pair always kept watch, soaring in wide circles high above the tree, and when we attempted to climb it, the big dangerous-looking bird came swooping down at us and drove us away.

We greatly admired the plucky kingbird. In Scotland our great ambition was to be good fighters, and we admired this quality in the handsome little chattering flycatcher that whips all the other birds. He was particularly angry when plundering jays and hawks came near his home, and took pains to thrash them not only away from the nest-tree but out of the neighborhood. The nest was usually built on a bur oak near a meadow where insects were abundant, and where no undesirable visitor could approach without being discovered.

When a hen-hawk hove in sight, the male immediately set off after him, and it was ridiculous to see that great, strong bird hurrying away as fast as his clumsy wings would carry him, as soon as he saw the little, waspish kingbird coming. But the kingbird easily overtook him, flew just a few feet above him, and with a lot of chattering, scolding notes kept diving and striking him on the back of the head until tired; then he alighted to rest on the hawk's broad shoulders, still scolding and chattering as he rode along, like an angry boy pouring out vials of wrath.

Then, up and at him again with his sharp bill; and after he had thus driven and ridden his big enemy a mile or so from the nest, he went home to his mate, chuckling and bragging as if trying to tell her what a wonderful fellow he was. This first spring, while some of the birds were still building their nests and very few young ones had yet tried to fly, father hired a Yankee to assist in clearing eight or ten acres of the best ground for a field. We found new wonders every day and often had to call on this Yankee to solve puzzling questions.

We asked him one day if there was any bird in America that the kingbird couldn't whip. What about the sandhill crane? Could he whip that long-legged, long-billed fellow? We never tired listening to the wonderful whip-poor-will.