U.S. Renewable Electricity Generation: Resources and Challenges

For natural gas and other fossil fuel power plants, the cost of fuel may be passed onto the consumer, lowering the risk associated with the initial investment though increasing the risk of erratic electric bills. However, if costs over the lifespan of energy projects are taken into account, wind and utility-scale solar can be the least expensive energy generating sources, according to asset management company Lazard. Even more encouragingly, renewable energy capital costs have fallen dramatically since the early s, and will likely continue to do so.

Selecting an appropriate site for renewables can be challenging.

Nuclear power, coal, and natural gas are all highly centralized sources of power, meaning they rely on relatively few high output power plants. Wind and solar, on the other hand, offer a decentralized model, in which smaller generating stations, spread across a large area, work together to provide power. Decentralization offers a few key advantages including, importantly, grid resilience , but it also presents barriers: Siting is the need to locate things like wind turbines and solar farms on pieces of land.

Doing so requires negotiations, contracts, permits, and community relations, all of which can increase costs and delay or kill projects. Because wind and solar are relative newcomers, most of what exists today was built to serve large fossil fuel and nuclear power plants. To adequately take advantage of these resources, new transmission infrastructure is needed—and transmission costs money, and needs to be sited.

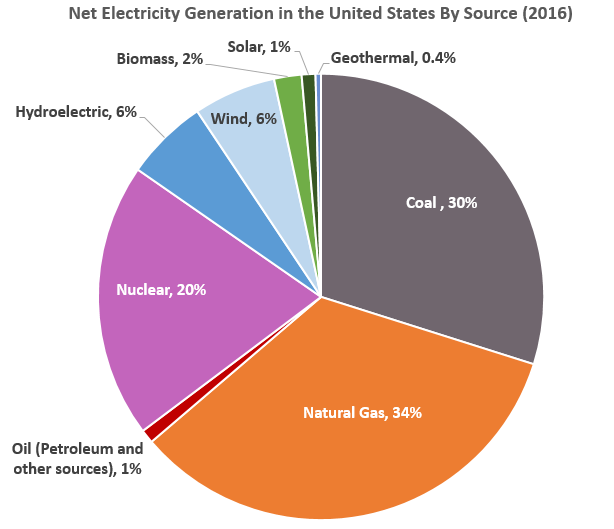

US electricity sources, Renewables face stiff competition from more established, higher-carbon sectors.

Search form

For most of the last century US electricity was dominated by certain major players, including coal, nuclear, and, most recently, natural gas. Utilities across the country have invested heavily in these technologies, which are very mature and well understood, and which hold enormous market power. This situation—the well-established nature of existing technologies—presents a formidable barrier for renewable energy. Solar, wind, and other renewable resources need to compete with wealthier industries that benefit from existing infrastructure, expertise, and policy.

New energy technologies—startups—face even larger barriers. They compete with major market players like coal and gas, and with proven, low-cost solar and wind technologies. Large amounts of acidic and alkaline wastewater are produced, so wastewater treatment and acid recycling are also critical steps.

Fluoride in wastewater poses special problems, because an excessive amount of fluoride in drinking water can cause a variety of diseases. Thus, strict standards are necessary to regulate the treatment and discharge of water containing HF. These issues are discussed in more detail in Appendix D , where research for reducing environmental and health and safety issues associated with polysilicon manufacturing are highlighted.

Renewable energy facilities, like other means of electricity production, can have significant environmental and socio-cultural impacts. For renewable technologies, these impacts are often, but not always, similar to or milder than the effects of other industrial development on a similar scale. Nonetheless, locating renewable energy projects in sensitive areas can make the environmental licensing of the project difficult and more costly, and so these project-scale impacts can affect the rate of deployment.

Among renewable electricity technologies, large-scale hydroelectric projects have historically had especially stark consequences, especially if they involved flooding scenic valleys or town sites. For example, when the Dalles Dam on the Columbia River was completed in , the associated reservoir flooded Celilo Falls and the village of Celilo, a tribal fishing area and cultural center that archeologists estimated had been inhabited for millennia Oregon Historical Quarterly, Like other dams on the Columbia River, the Dalles Dam serves multiple purposes, including improved navigation, irrigation, flood control, and the generation of nearly 1, MW of electricity.

Although the Dalles Dam has provided. Since the Dalles Dam was completed, a web of U. These include the Wilderness Act, which prohibits activities that damage the character of wilderness in specified areas, the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, which bans construction of dams and associated hydroelectric projects on protected stretches of rivers, and the National Environmental Policy Act NEPA , which requires that environmental reviews be completed with full opportunities for public input before federal actions are taken.

In part because of these protections, the pace of large-scale reservoir construction in the United States has slowed dramatically since the s, and most new U.

Barriers to Renewable Energy Technologies

At the same time, however, as plans for utility-scale wind and solar projects move forward in the United States, advocates will have to take great care in siting and designing projects and operations that minimize environmental and social costs. A case in Hawaii is another example of controversy surrounding the siting of renewable energy projects in locations of natural, cultural, or religious value.

In , Hawaiians celebrated the protection of a 26, acre tract of lowland rainforest on the island of Hawaii, after more than 20 years of efforts to restore public access and block the development of a geothermal power plant at the site OHA, In the late s, True Geothermal Energy Co.

Native Hawaiians opposed the development because they traditionally used the area for hunting and gathering and for religious purposes. Some native Hawaiians also objected to the exploitation of geothermal resources in general because of reverence for Pele, the goddess of volcanoes in the native Hawaiian religion. The Wao Kele O Puna geothermal project was abandoned in When the land was subsequently offered for sale, the Pele Defense Fund, a native Hawaiian group, approached the Trust for Public Land to arrange a purchase for conservation purposes.

After hydropower, whose impacts have been fairly well documented e. Collisions with wind turbines have killed birds and bats; the numbers depend in. In the United States, wind turbines were estimated to have killed roughly 20, to 40, birds in NRC, Although these totals are much smaller than the hundreds of millions of bird deaths nationwide attributed to collisions with buildings, high-tension lines, and motor vehicles, localized impacts on specific bird populations can be significant.

For example, raptor fatalities at the Altamont Pass wind site in California in the s caused significant concerns. Relatively limited data on bat deaths from wind turbines are available, but mortality rates at some facilities are as high as 40 recovered carcasses per MW per year NRC, However, ecologists warn that as wind energy development accelerates in the United States, the potential for biologically significant impacts on bats is a major concern Kunz et al. In the past decade, the wind industry in the United States has been required to pay more attention to siting considerations and equipment modifications to reduce animal mortality rates.

The Fish and Wildlife Service FWS, has issued interim guidelines for minimizing the impacts of wind projects on wildlife, and an effort to revise and update them is currently under way. These concerns are embodied in substantive laws that can go beyond imposing procedural requirements as NEPA does to sharply curtail or block development in some areas.

ESA requires consultation with the Fish and Wildlife Service before initiation of projects that require federal action. Even for project development on private lands, consultation is recommended to avoid incidental harm. If there is a potential for incidental harm, project developers may proceed by securing an incidental take permit, which typically entails developing and implementing a habitat conservation plan and appropriate mitigation measures.

Aesthetic concerns may not be specifically regulated but can be a significant issue for communities where new renewable energy projects will be located. The NRC study of environmental impacts of wind energy notes that in many countries and cultures, people form strong attachments to the place where they live that influence their reaction to new developments. Wind farms in particular. Moreover, as with other renewable energy facilities, they are often proposed for locations where there has been no prior industrial development.

The NRC study recommends a visual impact assessment process for determining whether a particular wind project would result in undue harm to valuable aesthetic resources and cautions that meaningful public involvement is crucial for acceptance. These same concerns would apply for transmission lines as well, and thus could become an important factor in the acceptability of large-scale renewables projects requiring new transmission. Under NEPA and similar state laws , federal or state agencies must assess in advance the environmental impacts of their actions.

Actions that fall under NEPA requirements range from the provision of loan guarantees for renewable energy projects to the granting of rights-of-way or the issuance of leases for construction of projects or transmission lines on or across federal lands. The objective of NEPA is to ensure that agencies fully consider potential environmental impacts and allow all interested parties, including the public, to provide input into the process before decisions are made.

The process typically begins with a brief Environmental Assessment EA , the purpose of which is to determine whether the activity might impose a significant environmental impact. The majority of projects proceed with an EA, often after agreement has been reached on mitigation measures, and do not require full-blown EIS documents. However, large projects usually require a full assessment.

Department of Interior, has collaborated with the U. BLM assessments are important because the agency administers more than million acres of public land in the United States, almost all of it in the western half of the country and much of it rich in renewable energy resources. Each programmatic assessment addresses the implications of broad policies designed to facilitate private development of renewable energy on federal lands.

EIS studies examine potential environmental, social, and economic impacts on a broad scale, with the objective of assessing resource potential; identifying lands. As an example, the programmatic EIS for wind identifies potential impacts on soils; water resources and water quality; air quality; noise; vegetation; wildlife; paleontological resources; and cultural resources, including sacred landscapes, historic trails, and scenic vistas BLM, Impacts on soil, water, and air quality are expected to occur principally during project construction, whereas impacts on noise, wildlife, and scenic vistas are expected to continue throughout the life of the project.

Programmatic analyses have helped to streamline later assessments of individual projects but cannot supplant case-by-case analysis because impacts on natural and cultural resources are usually site specific. The Environmental Impact Assessment Law of mandates that a developer complete an environmental assessment before project construction. If not, the developer is required to complete a post-construction assessment. In recent years, numerous environmental disputes have arisen over the construction of waste incineration power plants. For example, protests by nearby residents against the construction of the Liulitun waste incineration power plant in Beijing had a significant social impact at the time.

Since then, a mechanism for public participation has been introduced. For controversial projects that are environmentally sensitive, local governments are responsible for explaining the project to the public and for holding public hearings, if necessary. Like other economic sectors, the electric power sector generation, transmission, and distribution facilities in the United States is covered by a wide range of land-use and environmental regulations that encompass the development and construction of new facilities, facility operation, and decommissioning and site restoration.

Project developers must typically attend to layers of local, tribal, state, and federal regulations and deal with multiple agencies and permitting processes.

Barriers to Renewable Energy Technologies

Thus the complexities of planning and permitting may be multiplied in terms of approval steps and timelines due to the number of parties involved. Special protections or bans on development may apply to lands including privately owned land with special designations, including historic sites, prime farmland, and wilderness and roadless areas. Federal NEPA requirements apply for any electrical generating facilities or transmission lines on federally managed public lands or offshore.

Approximately 30 percent of the land in the United States is federal public land, and public lands are especially prevalent in the western United States, where significant wind, solar, geothermal, and hydropower resources are located. The American Wind Energy Association has compiled a guidance document that outlines the types of local-scale environmental impacts that can arise and the corresponding regulatory framework that governs the development of wind energy projects AWEA, Projects developed on private lands face an array of local, tribal, state, and federal land-use and environmental review and permitting requirements designed to ensure that potential impacts are identified and mitigated.

Siting and land-use regulations for privately owned land are usually the purview of state, tribal, or local governments, and hence vary widely across the country. In some states, public utility or state energy siting boards have jurisdiction to review and authorize new electricity generation facilities.

State environmental quality and wildlife conservation agencies may implement requirements for environmental review. In other states, or for relatively small projects, siting decisions may be left to municipal or county agencies. Whether or not state-level approval is required, almost all projects on private land require local review for compliance with zoning restrictions and ordinances limiting height, setbacks, and noise.

Renewable energy projects that release contaminants into air or water or thermal pollution to surface bodies of water may also be subject to state and federal regulations. The primary laws governing air and water pollution in the United States are the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act, both of which include direct federal regulations as well as programs that are mandated and enforced by the federal government but administered by states or tribes.

Compliance with air pollution regulations under the Clean Air Act is required for biomass combustion and geothermal facilities that release pollutants to the atmosphere during operation; other renewable projects that entail clearing land or construction of new roads may also have to address concerns about vehicle or construction equipment emissions and fugitive dust.

Biomass, geothermal, and solar thermal power plants that discharge cooling water to lakes or rivers face regulation for thermal pollution as well as contaminant discharges. Discharge permits may also be required for renewable energy projects that use water during exploration or production phases, including for sanitation and dust suppression. Confronted with multiple pressures, such as the need for economic development, expanded employment, and mitigation of GHG emissions, the Chinese government has promulgated policies and implemented laws on energy conserva-.

However, to avoid or mitigate environmental, cultural, ecological, and scenic impacts, the development of renewable energy projects is subject to other national laws and regulations. Specifically, projects that involve feed-in power generation from renewable energy must secure administrative permits and submit information in conformance with relevant laws or provisions of the State Council. Western China, for example, is the birthplace of Chinese civilization. Throughout history, people of many nationalities have developed and created a rich and valuable cultural heritage, and artifacts in the region are the historical testimony that people of all ethnic groups developed the region and lived there together.

Since the adoption of the Renewable Energy Law, additional environmental regulations have appeared in China specifically to address environmental impacts of biomass power generation. In accordance with the new provisions, the construction and operation of waste incinerators must meet national or industry standards such as GB Solid Waste Incineration Pollution Control Standard , and the quantity and quality of garbage must be guaranteed. At present, to qualify as a biomass power generation project, the proportion of conventional fuel fed into the furnace by mass must be limited to 20 percent when a fluidized bed incinerator is used to deal with solid waste.

Some local governments faced with economic development pressures, a lack of modern technology, and a shortage of capital have been lax in implementing or enforcing laws and codes, although this situation is improving. Lessons from the experience of developed countries and increased capital investment can further improve the implementation of standards.

As public awareness of and interest in environmental issues increases in China, there are likely to be projects that attract public opposition. In comparison to fossil fuels, renewable sources of electricity such as solar, wind, and geothermal can offer substantial environmental benefits, especially with.

When life cycle emissions are considered, all forms of renewable electricity production are expected to have significantly lower GHG emissions per unit of electricity produced than generation from conventional coal and natural gas plants. With the exception of emissions of NO x and carbonaceous materials from biomass combustion, rates of life cycle emissions of conventional air pollutants from renewable electricity generation are also sharply lower than from coal and natural gas plants.

Although renewable energy sources have major advantages over fossil fuels, they also raise some environmental concerns. Many renewable energy technologies are ready for accelerated deployment, but research and development are still needed to reduce their environmental impacts. While wind, solar PV, and some geothermal plants have very low water requirements, biomass, concentrating solar thermal, and some geothermal plants generally have requirements comparable to those of other thermoelectric facilities.

The United States and China would benefit from efforts to further improve cost effectiveness and efficiency of low water-use cooling systems to help expand their utilization. Also, as a result of evaporation, water consumption associated with large-scale hydropower plants and other uses of associated reservoirs is particularly high. The United States also exports and imports some electricity to and from Canada and Mexico. Energy Information Administration EIA publishes data on two general types of electricity generation and electricity generating capacity:.

In , net generation of electricity from utility-scale generators in the United States was about 4. EIA estimates that an additional 24 billion kWh or 0. EIA estimates that total direct use of net electricity generation in equaled about billion kWh. The shares of U. Having sufficient capacity to generate electric power is important.

The physical properties of electricity require that enough electricity be produced and placed on the electric power system, or grid , at every moment to instantaneously balance electricity demand. Most of the time, many power plants are not generating electricity at their full capacities. Three major types of generating units vary by intended usage:. Generators powered by wind and solar energy supply electricity only when these resources are available i. When these renewable generators are operating, they may reduce the amount of electricity required from other generators to supply the grid.

Distributed generators are connected to the electricity grid, but they are mainly used to supply some or all of the electricity demand of individual buildings or facilities. Sometimes, these systems may generate more electricity than the facility consumes, in which case the surplus electricity is sent to the grid. Most small-scale solar photovoltaic systems are distributed generators.

At the end of , the United States had about 1,, MW—or 1. Generating units fueled primarily with natural gas account for the largest share of utility-scale electricity generating capacity in the United States. The shares of utility-scale electricity generating capacity by primary energy source were. The mix of energy sources for generating electricity in the United States has changed over time, especially in recent years.

Natural gas and renewable energy sources account for an increasing share of U. Most nuclear and hydropower plants were built before Nuclear energy's share of total U. Electricity generation from hydropower, historically the largest source of renewable electricity generation, fluctuates from year to year because of precipitation patterns. Renewable electricity generation from sources other than hydropower has steadily increased in recent years, mainly because of additions to wind and solar generating capacity.

In , the total annual electricity generation from utility-scale nonhydro renewable sources surpassed hydropower generation for the first time. Wind energy's share of total utility-scale electricity generating capacity in the United States grew from 0.