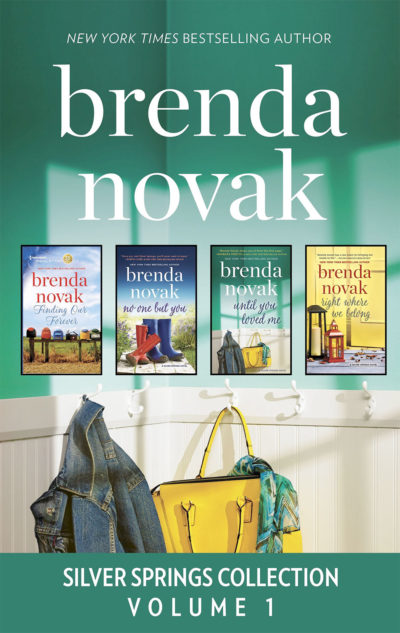

Silver Springs Contemporay Series - Books 1-4 (Silver Springs Contemporary Book 8)

Some new term in geography must be invented to describe this extraordinary land of many waters which has, I believe, less of a terraqueous ch 12 And then there are wetlands. Once reviled as swamps to be drained, or, later, ptly titled essay about Florida 13 In other words, wetlands are the shift ing thresholds between land and water, sometimes dry, sometimes submerged.

As late as , Florida contained an estimated More than half of 14 It 11 Ibid. Davis and Raymond Arsenault, eds. PAGE 30 30 southern part of the state, dominated by th e Everglades, was categorized as wetland. By , two years after the federal Clean Water Act was passed, Fl orida to 8.

That figure continued to drop into tection Act. A great deal of this disappearance took place to the south of Lake Okeechobee, in the enigmatic 15 Still, the presence of wetlands throughout the state helped define Florida in t he minds of many well into the twentieth century. Discovering the Unknown Landscape tracks changing perceptions about nature as demonstrated through attitudes toward wetlands. As early as , she notes, swamps w the descent whither the scum and filth that attends conviction for akened about his lost condition [and] there ariseth in his soul many fears, and doubts, and discouraging apprehensions, which all of them get together, and settle in this place; And this is the reason of the 16 15 Thomas E.

There are some discrepancies in the figures used by the different authors, 16 Vileisis, Discovering the Unknown Landscape 35, n PAGE 31 31 Florida, in many regar ds, suffered from similar perceptions even as mid nineteenth and early twentieth century Americans began to tout it as Edenic. In a way, rather than being unable to see the forest for the trees, many early visitors could not see the water for the swamps. Ironically, prior to the American period in Florida history, the as obstacles t 17 Even some early naturalists had difficulty the preceding day and this one in visiting the surrounding woods and the swamps where I was, but there were no interesting plants in this disagreeable place because 18 It is hard to imagine that the naturalist c ould find no interesting plants, as Florida is still home today to more than 4, native species of trees, shrubs, and flowering plants.

Norman, Andre Michaux in Florida: Natural Ecosystems and Native Species 1st ed. PAGE 32 32 day Jacksonville 20 Their legacy to Florida largely took the form of still life art and the documentation of birds and fauna. In the middle part of the nineteenth century, 21 When the first of the Hudson River romanticists, Thomas M oran, came to Florida, did achieve just that.

But where Moran failed or gave up believing that he had Martin 22 Indeed, Heade was ahead of his time in rejecting the idea uge for the contemplation 23 Water and land, in combination or often even convergence, have since dominated much of the popular visual art depicting Florida, from the works of the Highwaymen to the photography of Clyde Butcher, not to mention the vast majority of advertising and tourism art that has 20 Charlotte M.

Porter, "Following Bartram's 'Track': PAGE 33 33 been commissioned and created over the years. Much of this, however, has focused on the coasts and beaches. Florida certainly has no monopoly on coastline, nor do its rivers and lakes surpass in size or quantity those of many other states. Its annual rainfall is the same as that of Alabama and Mississippi. Its humidity can be extreme, but not very different from parts of Texas.

Now drained and re engineered, they are b ut a shadow of their former self, a patient on life support. The Everglades are a fascinating place with a rich history, and they provide a compelling their size and name, singular. The Everglades were not and generally are not a place National Park gre w steadily from its establishment in to a high of more than 1. Still, more than a third of visitors surveyed in were from Florida and nearly PAGE 34 34 three quarters of all visitors indicated that their visit was merely a day trip.

The Everglades were not a destination so much as a side trip. The combined population of Monroe, Hendry, and Collier counties, meanwhile, has grown to more than ,, but the vast majority live in the Florida Keys, on the west coast, or along Lake Okeechobee, respectively. Florida is home to more limestone artesian springs than anyplace else in America g and its largest are the largest in the known world. The springs of Florida offer a window into another world; one does not look into springs expanse before you, the waters of which are completely diaphanous or trans parent as behold yet something far more admirable, see whole armies [of fish] descending into the 24 "State and County QuickFacts," U.

PAGE 35 35 abyss, into the mouth of the bubbling fountain, they disappear! Are they gone forever? Seeing this hydrologic and biologic eruption teased the imagination and forced many early observers to wonder what was beyond, what was beneath the surface. Some, like Bartram, saw the possibility of underground worlds, connected by subterraneous rivers which wander in darkness beneath the surface of the earth by innumerable doublings, windings and secret labyr inths; no doubt in some places forming vast reservoirs and subterranean lakes, inhabited by multitudes of fish and aquatic animals and possibly.

As late ot unreasonable to suppose that these great Florida springs should produce samples of fauna which as probably been lurking in the bowels of the earth since Cretaceous times, perhaps a hundred million 28 But while these ideas may conjure scenes fr om Jules Verne novels, they are not without some kernels of truth. For millennia, as rain has fallen onto the southeastern portion of what would become the United States, most of it has returned to the atmosphere through evaporation, usually in a mere mat ter of days through evaporation and transpiration 26 William Bartram and Francis Harper, The Travels of William Bartram: Naturalist Edition Athens, Ga.

PAGE 36 36 from vegetation. However, some of that rain was absorbed into the soil and then seeped down further into a substratum of limestone known as the Floridan Aquifer, a combination of limestone and dolomite rang ing from to more than 3, feet thick and lying beneath an area of about 82, to , square miles, including all of Florida and parts of Alabama, Georgia, and even South Carolina. Because Florida has been repeatedly beneath the sea, the limestone of the Aquifer consists of a great deal of shells and fossils, making it especially vulnerable to erosion by carbon and carbonic acids.

Over time, rainwa ter that picked up carbon in the atmosphere or soil helped erode innumerable caverns and channels into the Aquifer. At the surface, meanwhile, the limestone is sometimes visible in what is called karst topography, a terrain characterized by sinkholes, springs, caves, disappearing streams and underground drainage channels 32 29 Fernald, Patton, and Anderson, Water Resources Atlas of Florida Scott, Springs of Florida Tallahassee, Fla. Alabama, Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina," Rosenau and George E.

Ferguson, Springs of Florida Rev. PAGE 37 37 So while the springs are the most not iceable manifestation, they are products of the same topography and geology that account for many of the other interesting features, wet and dry, that characterize the landscape of much of interior north and central Florida. Simmons and other early America n explorers who endeavored to explore the interior encountered an abundance of clear ponds, some of them surprisingly round and many of which are, in fact, ancient sinkholes filled with water from rain or from the Aquifer. Observed The waters of all of them are remarkably clear; hence they are termed in the 34 Untold numbers of these may still e xist, it should be added, yet those which have not been polluted remain largely unseen from roadsides, hidden behind woods or development.

Sinkholes themselves are essentially either stagnant or dry cousins of the springs.

A Rose Harbor Novel

Sometimes, as the limestone is er oded, the land above will gradually subside into it, leaving a depression or large hole. Other times, however, the underlying limestone is eaten away while the surface remains intact creating an underground cavern. When the weight of the roof is too great or the water table is particularly low and the cavern 33 Barry F. Beck, Si nkholes in Florida: An Introduction Orlando, Fla. PAGE 38 38 import car lot, public pool, and p art of a residential neighborhood and was referred to as 35 While sinkholes can remain dry or become pond like, they can also become springs.

The essential difference between sinkholes like those mentioned above and those that form springs is artesian pressure.

- The Other End of Nowhere.

- Browse Inventory!

- Thesis/Dissertation Information.

Where adequate water pressure to support the surface stratum is absent, a sink is created that may or may not fill with water. Where the water pressure in the Aquifer is great enough or the sink falls below the water leve l of the aquifer, water bursts through and springs are formed. In general, m ost Florida springs occur where the limestone aquifer intersects with the surface. Over the millennia, as sea levels and water tables rose and fell, springs ran at different rates and sometimes, when the water table was low enough and the land exposed high enough, stopped running altogether.

Or, when sea levels were high enoug h, seawater replaced the fresh and saline water of the Aquifer altogether and the springs ran salty. In general, though, much if not all of the Aquifer has remained saturated one way or another. Today, freshwater dominates the upper level of the Aquifer fr om which surface water is mainly derived, although withdrawals for development and agriculture have caused saltwater intrusion in some coastal areas. PAGE 39 39 ancient African geologic heritage. Where the surface stratum above it is a thin or porous materi al, such as sand or light clay, water simply seeks its own level its potentiometric level and can emerge in low areas as seepage springs.

- Haftarah - Wikipedia.

- Silver Linings by Debbie Macomber | www.newyorkethnicfood.com: Books.

- The Holy Grail of Holy Grail Theories.

- Prelude in B Minor, Op. 28, No. 6!

- Buy for others.

However, where the overlaying sediment is thicker or less permeable, such as with heavier clays, or where other hydrol ogic forces are brought to bear, pressure builds up. When that great enough and there is a fracture or permeation between the surface layer and the aquifer, water is fo 38 ground 39 proliferate, and the st ate has the largest number of first magnitude artesian springs those with average flow rates of just over 44, gallons per minute, or gpm in the United States, with 33 of the 84 total in the nation.

Additionally, t he vast majority of the more than total springs in Florida are artesian in nature. Ferguson, Springs of Florida Tallahassee, Fla. Ferguson, Springs of Florida 15; Elizabeth Purdum et al. The figures on the number of Florida springs vary between sources, but not by enough to warrant inclusion.

PAGE 40 40 42 In other words, rivers was not very far off base. And while Barbour and others may have hoped for living s amples of bygone fauna, the springs have proven to be excellent windows into the past not just as sources of time capsules that contain valuable information about our environmental and cultural pas the earliest human presence in Florida.

Abundant supplies of fresh water, aquatic food sources, chert, and clay made Florida's springs h ighly desirable habitation sites. Items recovered from Florida springs include tools, weapons, physical remains, and even preserved human brain matter dating back more than 10, years. PAGE 41 41 wrote archaeologist Wilfred Neill in after finding what appeared to be the tips of Suwannee era Paleo Indian weapons and other artifacts near mastodon and mammoth rowing body of evidence suggests that the makers of Suwannee points were actually in contact with 46 Divers today can still find fossils and other remains of life long departed, but they wou ld be hard their river runs.

Prehistoric bowfin and longnose gar are common in many spring runs, and the ancient alligator, the iconic symbol of Florida, seems once again omnipres ent in most Florida waterways. In springs and their runs closer to either coast, the West Indian temperatures just above 70 degrees, these gentle giant sea cows seek ref uge there from the cold waters of the Atlantic and Gulf in winter.

The manatee, which Thomas looking of all the wild creatures of our years, and its ancestors for up to 45 million years. Schools of shiners, chubs, killifish and minnows dart between large r, predatory largemouth bass, bluegill, and black crappie. More than a half dozen species of turtle are often seen sunning themselves on 46 Wilfred T. PAGE 42 42 partially submerged branches and trunks of deadfall, falling off into the water like a squadron of fighter planes at th e too close approach of humans.

In the branches overhead, on land, or in the water beneath, the ever dangerous on the innocuous anhinga, or almost comical, spreading its wings wide to dry like its doppelganger, the double breasted cormorant and looking, for all the world, like an avian exhibitionist. On shore, observers can still see white tailed deer, wild boar, or even a black bear taking a drink from a spring or spring run. On some days, river otter may frolic incessantly near a spring boil or along the run.

At night, Amer ican eel emerge unseen from their underwater caves to join raccoon, bats, and other more nocturnal hunters, serenaded by the plaintive cries of limpkin or the bellows of amorous alligators. In the daytime, eels are not often seen, though one may think he o r she is passing over great schools of them. Aptly named eel grass abounds in many springs and provides shelter and habitat for smaller aquatic creatures, as do red Ludwigia, pond weeds, and other plants.

Perhaps attracted by the transparent waters and the ease of spotting their prey, fishing birds abound at most headed belted cooks for yo yaa s o f red tailed grackle. Heron of all shapes and sizes strut along PAGE 43 43 the shore amidst wood stork, ibises, and stilts. Cart oonish pileated woodpeckers may chase each other around the base of red maple trees while American coot and pied bill grebes float purposefully along through yellow bulbed spatterdock, white spider lily, and dazzling red cardinal flowers.

Around the knobby wooden stalagmites of bald cypress 48 greatly not only in their sizes, but also in their resident flora and fauna. The Silver Springs area, for example, the largest of the springs, contains a total of thirty seve n species of fish, ten amphibian species, and thirty varieties of reptile. Along and above its banks, eighty six species of birds have been known to visit or reside there along with twenty varieties of mammal.

These numbers are impressive since Silver Spri ngs is in a developed area that abuts Ocala, a city of over 50, and center of a metropolitan statistical area of more than , Still, at the far more remote Ichetucknee Springs in rural Columbia County, by comparison, thirty nine species of fish a re present, but there are also seventeen types of amphibians, all but one of which are frogs. Meanwhile, there are forty six species of reptiles, including twenty three kinds of snake. Well over varieties of birds have been sighted there, and it is hom e to twenty nine kinds of mammals.

PAGE 44 44 many creatures not seen in any of the other two. Shrimp and crayfish, stingray, and pelican venture here, but are almost complete strangers to inland springs. And while one may argue that Florida has no more a monopoly on springs than it does on average rainfall or the number of lakes, its springs are indeed diff erent from those around the nation, and not just in the their superior sizes and quantity. First, almost none are geo n or are they for the most part considered mineral springs, the two types of springs best known as touri st destinations throughout the rest of the nation and world from the late eighteenth through the mean average air temperature and are unaffected by any underground h eat sources.

Warm and hot springs cover the globe: Most of the w ell known springs around the world are warm or hot thermal springs. Not a single one of the hot springs in the United States is classified among the seventy eight first magnitude springs. The Big Spring in Thermopolis, Wyoming, which lays claim to being one of the largest hot springs in the world, has an average flow of about 3, gallons per minute, or gpm, w hile the entire Hot Springs grouping there discharges 4, gpm. By definition, each of three first magnitude springs, by comparison, has a minimum average flow of about 44, gpm, or more than nine times the flow of the entire Thermopoli s system.

The flow at Silver Springs emanates from sixteen different springs set around its slightly oblong springhead which measures about feet by feet and along th e first 3, feet or so of its six mile spring run to the Ocklawaha River About half of the flow issues fro m the main spring at the spring head. Silver Springs and the densely 51 George W. Grimm, and Joy A. Smith and George M. Heasler, and Jon K. PAGE 46 46 wooded run are part of the larger Ocklawaha River Valley, noted for its exten sive cypress strands hardwoods, wetlands and exceptional fish and game populations The spring run, known as the Silver River, follows a winding and narrowing course eastward into the Ocklawaha River.

The Ocklawaha, in turn, once perhaps the ancient coas tline of Florida itself, runs in a windy northern direction from its origins in a chain of lakes in Lake County and then eastward to its confluence with the St. Johns River across from Welaka a distance of roughly seventy five miles Although awesome in i ts discharge much of what comes from a main spring near the top of the run, the springs create a gentle current of ab o ut one half mile per hour over depths of between six and thirty feet along its course.

The temperature of the crystal clear water fluctua tes only a couple of degrees, from 72 to 74 degrees Fahrenheit, and the flow rates are generally steady outside of drought years or significant weather events such as hurricanes. A dam has since been built and a large reservoir created along the Ocklawaha, which will be discussed in a later chapter.

PAGE 47 47 did develop in Florida, but not at any of the major springs. Instead, they cropped up at smaller springs in relatively remote places and most arose only after s 56 The role of springs generally in helping to create a leisure and tourist class in the United States will be discussed further in C hapter 3 clusters of large, non thermal springs. There are a handful of other clusters of first magnitude springs around the U. Of those, only the Ozark and Texas springs are limestone springs and only the Te xas springs occur in relatively the low relief of the land, the dense vegetation, and the mantle of sandy soil through which the water largely enters the lim estone, the spring water is very clear and does not 57 Then, because of the active circulation of the large volume of water being held within the aquifer, the water remains very clear as it passes through the limestone quickly enough to generally avoid picking up soluble minerals.

Gov't Printing Office, , 9. PAGE 48 48 comes from an area called the upper aquifer and spring waters have been estimated through chemical dating to have fallen only between about eight and sixty years ago. With a shallow base of light colored sand and sediment t sunshine, the water can be illuminated in a manner and to an extent that springs in high relief areas like the Ozarks cannot. To wit, Black Spring in Jackson County is highly colored with organic matter; Green Cove Springs in Clay County emits a sulfur odor; Salt Spring in Marion County is, as its name implies, salty; Copper Spring in Dixie County has deposits o f iron around the pool and its run; Indian Springs in Gadsden County yields water whose dissolved solids concentration is as low as any water in the natural environment in Florida.

Warm Mineral Springs, for example, has a flow rate equivalent to that of the Thermopolis grouping. Salt Spring, along Lake George, is a colder but more mineral laden body than Warm Mineral Springs, and is even nine times larger than that. N more than a half billion gallons per day, or enough to supply the residential usage of 59 Scott, Springs of Florida PAGE 49 49 Wisconsin, with more than half again left over.

Yet, for all inaccessible well into the nineteenth century, even as some of their cousins around the nation were becoming famed resorts. The last addition to the Americ an family east of the Mississippi, Florida remained to most a distant and exotic land. Its heart, the interior peninsula, was a frontier as forbidding and savage as any other on the continent and in the imagination. Florida had for centuries been an exotic and mythic place, which offered a potential Eden or Fountain of Youth.

The jewel in its crown of springs would be Silver Springs, but to get there, one first had to cross through the Slough of Dispond. It would more than three centuries years for that reg ion to be tamed and made accessible. As historian Gary Mormino describe s an imperial outpost to its modern identity as tourist empire, Florida has evoked contrasting and compelling images of the sacred and profane: Even on the eve of its incorporation into the United States as territory in , skeptics abounded When the issue of acquisition came before the House of Representatives for debate, for example, Virg inia Congressman John Randolph reportedly declared, alligators and mosquitoes!

A man, sir, would not immigrate into Florida no, not from 2 Indeed, relegate d largely to the dry and sandy coasts until the nineteenth century, Europeans found life on the land hard going. At the end of t he seventeenth century, Spanish governed cen tury, the fortunes seemed ready to turn but the outbreak of war 1 Gary Ross Mormino, Land of Sunshine, State of Dreams: Buker, "The Americanization of St.

Saga of Survival Jean Parker Waterbury ed. A mere twenty years later, the Floridas were returned to Spanish control 3 It was not until Anglophones began encounteri ng and describing the peninsular interior that Americans began to warm to the potential of the land and that Florida as a desirable place entered into the American imagination.

Bartram, as noted, offered some of the first positive notions of Florida to th e American people, but where he saw an intrinsic beauty in the flora, fauna, and topography of the Florida interior, most descriptions at the beginning of the nineteenth century were far more utilitarian. Strategic, economic, and expansionist motives engen dered descriptions of Florida in terms of its potential agricultural and commercial productivity. In the first four decades of the nineteenth century, as physical and political obstacles impeded the settlement of the northern interior, the Florida garden r emained largely unknown to all but Bartram and few others.

That would change only after the Second Seminole War pushed the frontier into and beyond the spring laden interior of Florida. PAGE 52 52 ambiguous enough as to be almost unrecognizable. It was the antithesis of Eden. Historian Roderick Frazier Nash writes that any notions of a New World Eden seventeenth century frontiersman realized that the New World was the antipode of 7 The same can easily be said, it will be shown, for early explorers of the Floridas, from the conquistadors through the first generations who settled there when it ites of colonial New England, citing Franc the alligators of Florida, especially in the hyperbolic descrip tions of early explorers.

Definition used is 2a. Other 7 Nash, Wilderness and the American Mind PAGE 53 53 Nash wr ites 8 The natives of Florida were of ten no different in the minds of numerous explorers and settlers who described them in similar terms, and would remain so well into the nineteenth century. Wilderness, to Americans at the time, was a thing to be conquered, tamed, and settled as part of God unconquered, untamed, and largely unsettled by whites First to arrive in the New World from Europe had been the Spanish, led by Juan Ponce de Leon, in After several acrimonious encounters with the natives of Florida, Juan Ponce ultimately died from wounds suffered fighting the Calusa in Subsequent expeditions to Florida under Alonso Alvarez de Pineda in , Lucas Vazquez de Ayllon in , Tristan de Luna y Arellana in , and Angel de Villafane in all ended without the establishment of a viable colony.

The disastrous Panfilo de Narvaez expedition of ended with some of the earliest writings about Florida, courtesy of Alv ar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca, who detailed a plight of hunger, sickness, and continuous assaults by natives. Ultimately, the survivors of that expedition, having lost contact with the ships that brought them there, decided to take their chances on the water in makeshift rafts rather than remain in Florida. Despite being on the banks of the immensely bountiful seafood and shellfish buffet that was the Gulf of Mexico, the men the unfavorable accounts of the population and of everything else we heard, the Indians making continual war upon us.

PAGE 54 54 themselves that we could not retaliate. Nonetheless, between and , at least fourteen additional garrisons were e stablished in the region, not one of which lasted even three years. Six inland garrisons were abandoned within less than a year. Resistant natives and lack of food were to blame in virtually every case. Au gustine on September 8, , the Spanish began a brutal expulsion of a contingent of French Huguenots who had actually arrived prior to Menendez under the command of Jean Ribault.

In his precious little time in Florida, Ribault thought he had found a para 11 But Menendez was not about to share Spanish claimed soil and, in two bloody episodes in late September and October, he executed Ribault and about of his men even after their surrenders at an inlet south of Anastasia Island that henceforward has borne the One survivor of the ordeal was left with quite 9 Alvar Nunez Ca beza de Vaca, "Narrative of Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca," in Visions of the Old South: Eyewitness Accounts, Alan Gallay, ed. Hoffman, Florida's Frontiers Bloomington, Ind. A Facsim Reproduction Gainesville, Fla.

With the that would continue for the next si x years. The mission system, an effort to establish a Spanish and Christian presence throughout the colony, failed largely to do anything but alienate natives and accelerate their mortality rates. Although primary sources are slim, historian Robert Allen Matter paints this picture of the mission frontier: The Spanish missions of Florida did not conform to the romantic notion of cloistered gardens, tolling bells, handsome churches set in idyllic villages s urrounded by bountiful fields and orchards and grazing live stock, although a few of those features occasionally were present.

The impression gained from available documents, published sources, archaeological research, and from the author's visits to many mission sites is one of stark realism, revealing crude buildings and tools and poverty more often than plenty. Pestilence and war, plus discord, martyrdom, and toil by a handful of 12 Thomas Hallock, "Between Topos and the Terra in: Davis and Raymond Arsenault, ed. PAGE 56 56 Franciscans, their Indian converts, and a few Spanish soldiers in a primiti ve wilderness complete the picture.

When the War of Spanish Succession reached the shores of America, where it came to be k nown as Queen and invaded the Floridas laying ission system was gone from Florida and as many as 10, to 12, mission Indians had been seized by the British as slaves, leaving behind only a few hundred Christianized natives. Spain's La Florida was little more than what it had been in , a garrison precariously perc hed on a sand spit by the Atlantic Ocean.

The Early Catholic Church in Florida, 2nd ed. PAGE 57 57 cast wherein man had been expelled from the fertile Eden to a barren desert on the fringe of howling wilderness. To the north, British North Americans in the southern colonies may have been familiar with Florida not just as a haven for escaped slaves and unfriendly natives, but also as just the type of wilderness that Adam and Eve encountered. As Nash explains, 17 When Jonathan Dickinson and his family were shi pwrecked on the Florida east coast in , Dickinson trees, but only sandy hills covered with shrubby palmetto, the stalks of which were 18 Dickinson and his party were beset by fierce weather, hunger, and sometimes 19 The d his popular account, which was reprinted more than a dozen times between and PAGE 58 58 coast and did not encounter what would surely have struck them as more providential terrain: Citing Scripture, Nash explain s the dichotomy of wi lderness and 21 Yet for Dickinson and seemingly every other European who experienced Florida and put pen to p aper, the fountains and springs of the Florida interior remained beyond the visible horizon and without the least intention of irony.

They encountered the sandy soils of t he beaches and coastal strands as one would a desert island, but also through the lens of their religious beliefs: As Nash wr ites he identification of the arid wasteland with God's curse led to the conviction that wilderness was the environment of evil, and Florida was both wilderness and wasteland. PAGE 59 59 an people do not choose to go out of the old beaten track, or [otherwise] content 24 Romans also did much to reinfor 25 One of the major land grantees in British Florida was Dr. In his account of East Florida for the Lord Treasurer, the Marquis of Rockingham, Stork suggested that Florida woul d inevitably become agriculturally productive because it was a southern colony and southern colonies in North America were more productive than those in the north.

He further reasoned that it would be productive also because it lay on the same sunny latitu 26 potential for agricultural production, he reasoned, did so because of its deceptive coastal faade. PAGE 60 60 would tout in of language reinforces the notion that as long as Florida remained untamed and Augustine exce pted, this country is at present, for want of inhabitants, little better than a 28 The Florida interior was, in the late eighteenth century, as the American Where 29 Stork, who had a vested interest in the success of Florida, would continue to boost Florida in various publications including a revised version of the above account that included a journal by John Bartr am.

But many writers in England mocked Florida, and the southern region of North America in general.

Silver Springs Contemporary Series

Translated from the French London, , xxxvi. PAGE 61 61 33 with special vitriol toward the pine barrens of the region, which were characterized by sparse undergrowth: Yet these are the only pastures they have in many of our colonies and es pecially in Florida if it be not in the miry and destructive swamps and marshes.

What is worse, these pernicious weeds are not to be extirpated; they have a wing to their seed, which disperses it everywhere with the winds, like thistles, and in two or thr ee years forms a pine thicket, which nothing can pass through nor live in. Thus the land becomes a perfect desert. However, this program was hampered by a land policy that did not take into account the st be continuous, one third as broad as it was long, and that it must run back from a waterway and not have its sides communicating with water.

As a result, it was difficult to lay out any tract without having a disproportionately large amount of poor soil 35 Would be colonist Denys Rolle a wealthy Englishman who dreamed of creating a utopian settlement in America, encountered this very obstacle, among many others, in his ill fated endeavors in East Florida. Rolle had originally planned to build his ideal community at St.

Marks near where de Vaca and his comrades had abandoned Florida to take their chances on the water. Collected from the Best Authorities by William Roberts. Jefferys London, , Johns River area upriver from St. Augustine in the mid s because h e believed a trip through the Florida interior would result in his party being scalped by the European conception of wilderness.

Rolle then complained that th ere was too much pine barren in eastern Florida to find a 20, acre contiguous tract that was anything nd, out of the entire 20, acres.

Silver Linings

Other less restrictive land policies by the British followed, but their rule in East and West Florida, even as the population swelled around St. Augustine from Loyalist refugees during the American war for Independence, was in its last days. PAGE 63 63 upper stratum of the earth of which is fine white sand and pebbles, and at some distance appears entirely covered with low trees and shrubs of various kinds and of equal height. Augustine never exceeded 2, 2, people. Meanwhile, the newly constituted nation to the north quickly began making inroads on other parts of Spanish Florida.

During the British period, Florida had welcomed its greatest admirer, the above mentioned William Bartram and his writings would help change the way Florida would be perce ived for peninsular Florida, Travels, finding instead of desert or wilderness, something much closer to Ede n. Bartram, unafraid to brave the Florida interior alone in , had been looking for natural beauty of a kind not found in his home of Pennsylvania and its neighboring colonies.

PAGE 64 64 of curiosity, in pursuit of new productions of nature, my chief happiness consisted in tracing and admiring the [e]nchanting little Isle of Palms. This delightful spot, planted by nature. Rising from the limpid waters of the lake. A fascinating atmosphere surroun 41 While the Bartram was able to experience the aqueous and florid spring laden interior. Although both would be redefined over the next two centuries the dichotomy between coastal and interior Florida was as stark then as it is today.

As starkly different as the interior was from the coast physically, it was also very different symbolically. Where the coast was desert, Bartram found the interior to b e the garden. And although this paradise of fish may seem to exhibit a just representation of the peaceable and happy state of natur e which existed before the fall, yet in reality it is a mere representation; for the nature of the fish is the same as if they were in Lake George of the river; but here the water or element in which they live and move, is so perfectly clear and transparen t, it places them all on an equality with regard to their ability to injure or escape from 42 41 The Travels of William Bartram PAGE 65 65 den, exists.

Spain, in the midst of its long free fall from empire sta tus, was busy with rebellions in its Caribbean territories as well as the Napoleonic Wars on the Continent and had little time or money to support and build its all but forgotten possessions, which often teetered on the brink of starvation. From the early middle eighteenth century through the early nineteenth century, a series of conflicts and treaties had resulted in the Creeks and other confederate tribes ceding territory in a retreating line away from the coast and South Carolina borders into southern and central Georgia.

This was true both in Washington and on the frontier. As historian Ken drick Babcock describe s possess the Floridas, between and , amounted almost to a disease, corrupting the moral sense of each succeeding [ p 45 For the most part, those administrations saw Florida from a strategic standpoint. The end of Spanish rule there was seemingly imminent and acquisition of Florida would exclude the British from potentially gaining a new foothold on the continent; it would buttress 43 Mackle, "The Eden of the South," McReynolds, The Semi noles 1st ed.

PAGE 66 66 American influenc e in the Caribbean Sea; and it would serve as a buffer against the influence of slave insurrections such as the revolt in Haiti. By the beginning of the nineteenth century, a sizeable number of Americans were already living in Spanish Florida both as squatters and as legitimate landholders. In , the Americans fomented a rebellion in, and then seized parts of, present day Louisiana part of Spanish West Florida at the time. In , a like minded group of Americans with tacit approval from President Madison sought to do the same in East Florida. The Patriot War, as it came to be known, began with a virtual invasion of East Florida in early , but the subsequent War of against the British complicated official American policy and the Patriot War degenerated into a stalemate punctuated with retaliatory violence and wanton destruction of property throughout East Florida.

By , it was over. In , seventy renegade American Mit chell near present day Micanopy and sought recognition from the American government. They determined quickly that the land they found in the Florida interior was better than that of Georgia: Compared to the nutrient poor soils that supported the ubiquitous pine and wire grass of southern Georgia, this loamy, productive soil attained almost legendary status among the Patriot farmers.

Cusick, The Other War of PAGE 67 67 grow "spontaneously," and wild vegetables were seen in abundance. Climate also played a factor in the minds of the settlers, and the mild winter that the Patriots apparently enjoyed in heralded a long and productive growing season. Crops and farms were destroyed and a U. By , Americans had al ready established inroads in East and West Florida British fort on Prospect Bluff along the Apalachicola River where fugitive slaves had assembled. After destroying th e fort, the forces swarmed east to the Suwannee River region. Americans now had at least some working familiarity with the terrain of Florida region of which but the vaguest knowledge was possessed by the people of the United 49 Now the entire northern swath of the Floridas was at least a somewhat known 47 Chris Monaco, "Fort Mit chell and the Settlement of the Alachua Country," Florida Historical Quarterly 79, Summer Boyd, and Gerald M.

PAGE 68 68 entity, although the bulk of the interior was still terra incognita. So far, Americans prospective settlers and gover nment officials alike liked what they saw in what appeared to be an agricultural providence. Others, like Randolph, remained skeptical. With the end of Spanish occupation apparently imminent and inevitable, American settlers did not wait for the Adams Onis Treaty, which transferred Florida to the United 50 After Spain ceded Florida in , though, there was one more political obstacle aside from the myriad physical ones to extending the southern frontier: For the time being, the U.

Government officials, meanwhile, also may have been further swayed toward acquiring Florida by accounts from the First Seminole War, from which the firs t comprehensive first hand accounts of the interior finally were 50 Hoffman, Florida's Frontiers PAGE 69 69 produced. Upon completion of the acquisition o editorials heralding the event that illustrate the stark contrasts of opinions and beliefs about Florida. The first, from the Virginia Patriot event among the mo 53 The companion editorial, meanwhile, from the Charleston Courier ran under fill the bosoms of individuals with a species of exhilarating gas, producing fantastic hopes and visions, singular in their appearance and various in their exemplification.

It wou ld seem as if every wish was to be achieved in Florida, and every ill to terminate 54 Ambivalence, to be sure, was rife. Upon acquisition of Florida, its interior, between the Suwannee and St. Johns rivers and south of Alachua in particular the upper end of the peninsula , remained an unknown to many largely because Florida lacked adequate roads and, other than the St.

Johns River, most water routes remained unused or impassable. PAGE 70 70 expanded in , took up a great deal of the peninsular int erior. At the same time, the dependency and open conflict, the latter often a consequence of the former, giving would be settlers pause about setting up a homestead too far from e stablished populations.

In late , for example, during the waning years of the Spa nish tenure, the budding artist and naturalist Titian Ramsay Peale, zoologist George Ord, and entomologist Thomas Say had set out to explore along the St. Johns, but abandoned their effort soon after reaching Picolata when they heard numerous stories of c o nflicts between Europeans and N ative Americans both up and down the St.

Silver Spring Guitar Center Store

Johns River and even along the coast, near Mosquito Lagoon. PAGE 71 71 obstacle, the n travelling within it was even more of an impediment except to the most intrepid of travelers. The few accounts of interior Florida that are available often betray the biases of their writers, who usually had financial interests in the development of Flor ida, but they also provide interesting insight into the nature of the interior before wholesale European settlement and development redrew much of the landscape. Again, it was in those accounts that Americans learned of a Florida that was not a forbidding wilderness, but rather an inviting garden.

Colonel James Grant Forbes, who oversaw portions of the transfer from Spain, 58 Unfortunately, Forbes, a booster himself, introduced little new information, relying instead largely on previously published accounts. This did not, however, prevent him its soil, the salubrity of its air, the sublimity 59 Indeed, the very nature of wetlands entails they are not always submerged. If encountered during their dry periods, they may appear and are often in fa ct quite fertile lands. PAGE 72 72 all but unknown: From roughly present ut little 61 Unlike many who wrote about Florida in the early nineteenth century without visiting regions beyond the established coastal areas and perhaps a brief way up the St.

Johns River, S immons endeavored to explore the northern interior firsthand. He set out in late winter from St. Augustine to Alachua, which then encompassed a large part of the north central peninsula. Struck by a desire to be part of the American vanguard in Florid a, he had moved there immediately upon its acquisition by the United States in with the found. Augustine at the time, he would have first been met by a many millennia worth of gifts from the Appalachian Mountains studded with coquina outcroppings.

Sea oat and sea purslane the pioneer plants would both cover and anc hor the dunes on the mainland shore and barrier islands. The barrier islands themselves not only provided natural storm and surge protection for the mainland, but also created an estuarine medley of lagoons, inlets, and tidal flats.

At Guitar Center Silver Spring

Just inland from the co ast, the terrain would have changed quickly from scrub and marsh to hardwood forests, with cedars and red bays, and live oaks grown wooly with Spanish moss and resurrection fern. Further inland, to the St. Johns River, the pine forests dominated. PAGE 73 73 n immense and sterile forest of firs, interspersed with cypress and pine ponds, and inlets were fertile, and the pine barrens could be made to produce crops and pasturage. He offers little description of the trip, which would have brought him past the confluence with the Ocklawaha River and across massive Lake George.

Upon reaching Volusia, though, he marveled at the which very much adorns the river, giving a deep green margin to its dark and ample stream. Johns River, he would have discovered an area dominated by large stands of virgin longleaf pine as much of the north Florida interior and a great deal of the Southeast once was offering a canopy for turkey oaks and wiregrass. Traveling west southwestward, he entered what would later become the Ocala National Forest, moving from the pine flatwoods and hardwood h ammocks of the St. Johns area into higher, sandier terrain.

As he moved toward the center of the region, he encountered a 63 Ibid. PAGE 74 74 B when the seas were at their highes t. The Big S crub presented a great forest of arching sand pines providing cover for a dense understory of scrub oaks, myrtles, rusty lyonia, Beyond the Big Scrub as he neare d the Ocklawaha River he encountered sinkholes, some which filled from the aqui fer or from rainfall, presenting roundish lakes pure waters, unpassed, as yet, but by the wing of the eagle, or the wild duck. Instead, he turned the edge of the Alachua Savanna PAGE 75 75 65 In general, Simmons, found what he saw to be almost limitless potential for the around the Ocklawaha River and Orang become a major artery for Florida develo produce of the interior country obtain a water carriage to the St.

Johns but the vast bodies of oak timber with which the region abounds can be readily wafted to the points where they may be wanted for ship bu 66 Rather than becoming a reliable conduit in and out of the interior, though, the persistent impassibility of the Ocklawaha would present perhaps the greatest single obstacle to development of that region well into the second half of the nineteenth century.

Another important evaluation of interior Florida during the early territorial years Florida, along with his book Observations Upon the Floridas, had at least so me influence in attracting early settlers to Florida. PAGE 76 76 into land there during the British period. Augustine and he did so perhaps more than once.

He had first arrived in St. Augustine in August, , just days before the outbreak of a yellow fever epidemic February, though, he wrote that he was preparing for a voyage around the peninsula to Tampa, where he would then make the overland excursion back to St. At the 69 Vignoles praised and rebutted the notion that the pine barrens that characterized much of the northern ote, they were, in fact, fertile. Indeed, the term pine barren comes from colonists in the northeast who found the soils sturage for cattle, and if sown with the the interior were potential treasure troves as well.

Vignoles, Life of Charles Blacker Vignoles PAGE 77 77 present day 70 Vignoles concluded that the vast potential of Florida should not be discou nted by the map he released with it. In it, a great swath of the northern penins ula, as far south as Tampa and consisting of most of the land west of the Ocklawaha and upper St. Just three years later, however, in February, 1 , after an inspection of the very lands from Alachua to Tampa Bay that Vignoles had described so glowingly, Governor lands were spoken of as being good, and I can say with truth that I have not seen three hundred acres of good land in my whole route after leaving the [Indian] Agency [near region, and there is no land in it worth 71 But 70 Vignoles, Observations Upon the Floridas 14, 74 PAGE 78 78 that did not, at that time, matter to most Americans, because this was land then reserved to the Seminoles.

Soon more Am ericans began to move into Florida, primarily from worn out lands or depleted opportunities in Georgia and South Carolina. Those with wealth moved into Middle Florida around the new capital at Tallahassee and established plantations, while livestock raising, where they could, further to the east, between the Suwannee and St. This was the new Florid a frontier and the Americans wanted to push deeper into what was still, to them, the wilderness of the peninsula. Indeed, the presence of the Seminoles was a critical part of how wilderness was perceived before the turn of the twentieth century.

As Roderick Nash note s s, and still 74 developed albeit far away from the frontier of Florida , the image was one of dualism, in which natives possessed both noble and ignoble traits. This not only just ified the idea of 72 Hoffman, Florida's Frontiers Johns, Suwannee, Santa Fe, and Withlacoochee rivers. These rivers all were outside the boundaries of the Seminole reservation, yet far enough from fortified Am erican settlements to qualify as retreated to concentrated garrisons or left Florida altogether, while the military established new outposts throughout Florida.

The ups hot for interior development abandoned, while outposts near others allowed not only for the establishment of communities there, but also for soldiers to describe them to other A mericans for the first time. By the end of the war, the Seminoles had been relegated to the southern part of the peninsula, and Florida was well on its way to statehood. Much of the former reservation was platted and offered for sale to the next generatio n of Florida pioneers. PAGE 80 80 Officials began turning toward developing a viable infrastructure an objective that would prove elusive to , in Nor would they read or hear of it as an Eden that was yet to c ome.

Instead, thanks to the early boosters and those who came after them, Florida had entered the American mind as a place of arable and productive and available lands for homesteading. Florida also was starting to make a name for itself as a resort desti nation, especially for the physically infirm.

Noting the temperate climate, William Cullen Bryant I do not wonder, therefore, that it is so much the resort of invalids; it would be more so if the softness of its atmosphere and the beaut y and serenity of its 77 In an era when springs around the country were the phenomenon. Yet, as will be shown in C hapter 4 only a handful became spa destinations before or after, for that matter the Civil War and of these, all were relatively small by Florida standards and their stints as resort destinations were extremely brief. Because of its peculiar history as a largely undeveloped Spanish foothold in North America, Fl orida had entered the United States inventory as a virtual unknown.

Most of its springs had yet to be discovered, let alone named or developed. Moreover, much of the interior was soon proscribed to whites to create the Seminole reservation, and the subsequ ent Second Seminole War to would both delay and, as importantly, help determine the directions of growth and development of the interior peninsula. In the meantime, springs and spring travel were in a period of unprecedented and since unsurpass ed popularity throughout much of the eastern United States.

As a result, interior Florida did not develop as a spring resort destination during the period and its identity its place in the American imagination remained undefined. The growth of springs trav el in the United States in the early and middle nineteenth century was spurred by two separate although often convergent phenomena The first was the eme r gence of a resort based tourist economy in which springs were primary destinations.

This began in the 1 In the nineteenth century, tourism and the primary role of springs in that tourism firmly took root. PAGE 82 82 century American society and cultur anachronistic European style class divisions, of religious revivalism, of the emergence artists and writers, am ong other themes. What is clear, though, is that Americans were experiencing a transformation in the way they viewed not only each other but also their physical environments, and springs were a critical component. Our repair technicians are as passionate about your guitars and basses as you are, and we have the experience needed to keep them performing at their best.

Whether you need a quick adjustment to make your guitar easier to play, or a complete guitar rebuild, we have the tools and know-how to take care of your instrument. We also take care of fret repairs, hardware and pickup installations, upgrades and customizations, bone and graphite services and more. Guitar Center Silver Spring. There's a lot of musical talent in our region, and Guitar Center Silver Spring is happy to count some of those talented individuals among our team. We know our stuff, so even if you're a gigging professional, we're ready to talk to you from a peer perspective about all the new, used and vintage instruments and accessories on our shelves.

We'd love to get to know you and hear more about your musical aspirations, so drop in for a visit or call us at to get started - and don't forget to ask for all the details about our free workshops and recording classes! Go to Site Get Directions. Guitar Center Social Media. Follow us on Instagram: View this video on YouTube. The new Les Paul Standard features the popular asymmetrical SlimTaper neck profile with Ultra-Modern weight relief for increased comfort and playability.

Impeccable looks are highlighted by the powerful tonewood combination of mahogany back and carved maple AAA figured top.