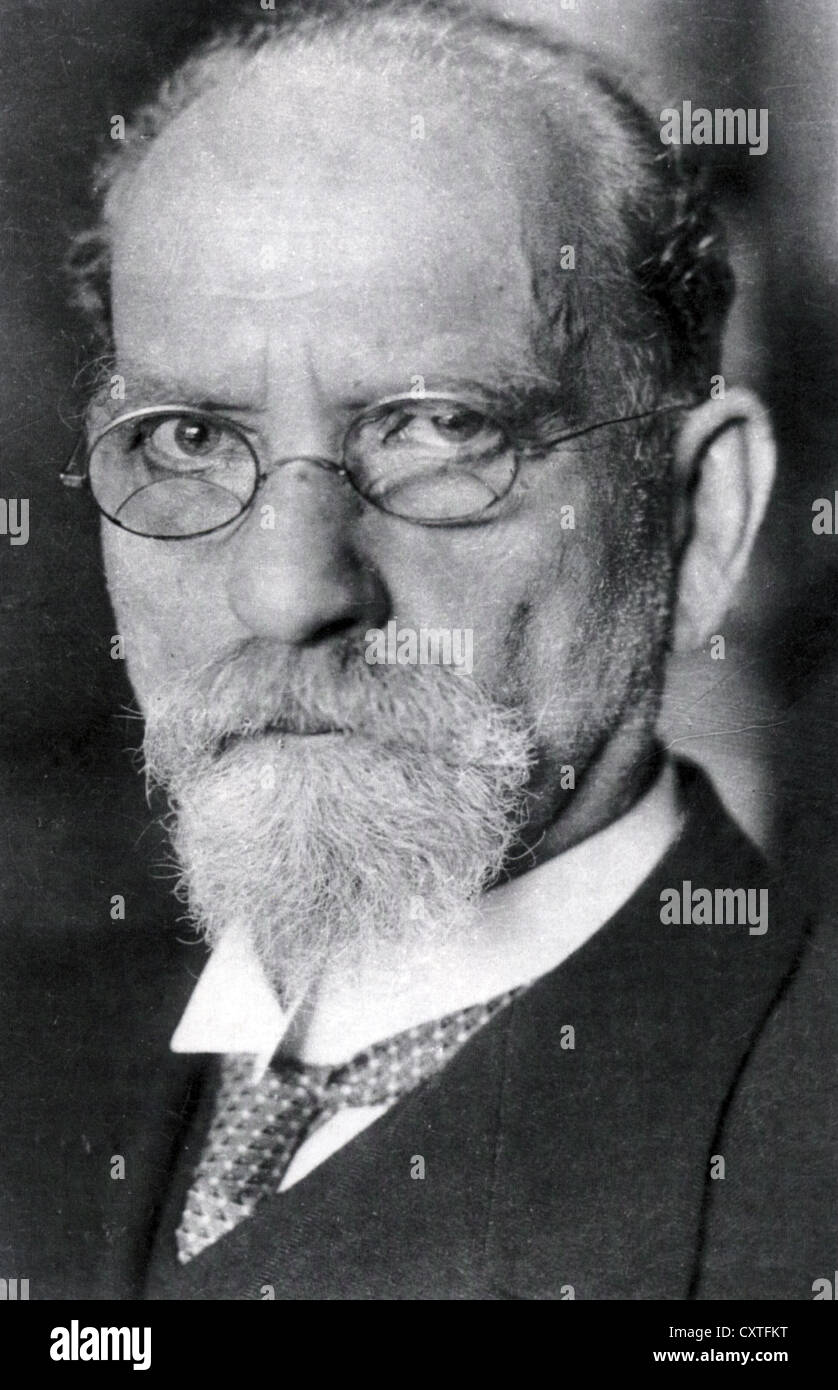

Edmund Husserl (1859-1938) (German Edition)

Psychologische Studien zur elementaren Logik: Prolegomena zur reinen Logik Halle Saale , Niemeyer.

Navigation menu

Logische Untersuchungen Halle Saale , Niemeyer. Philosophie als strenge Wissenschaft Logos. Filosofija, kak strogaja nauka Logos. Beitrag zur Diskussion zum Vortrag von Heinrich Maier: Niemeyer, , XI S. Der Wille zur Ewigkeit, Halle Saale: Ein Nachruf Kant-Studien Erinnerungen an Franz Brentano in: Die Idee einer philosophischen Kultur The Kaizo 1.

Edmund Husserl, Formale und transzendentale Logik Selbstanzeige. Formale und Transcendentale Logik General introduction to pure phenomenology New York, Macmillan. Vorwort Kant-Studien Edmund Husserl Selbstdarstellung in: Die Frage nach dem Ursprung der Geometrie als intentional-historiches Problem: Untersuchungen zur Genealogie der Logik Praha, Academia. Philosophical essays in memory of Edmund Husserl, Cambridge: Shaw und die Lebenskraft des Abendlandes Hamburger akademische Rundschau 3. September Philosophische Studien Neue Folge 2.

Erste Philosophie I Kritische Ideengeschichte Den Haag, Nijhoff. Erste Philosophie II Universale Teleologie Archivio di filosofia An introduction to phenomenology Den Haag, Nijhoff. Vorlesungen Sommersemester Den Haag, Nijhoff. Freges "Begriffschrift" in: The idea of phenomenology Den Haag, Nijhoff. The Paris lectures Den Haag, Nijhoff. Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt.

Logique formelle et logique transcendantale: Essai d'une critique de la raison logique Paris, Presses universitaires de France. Analysen zur passiven Synthesis: Funktion und Begriff in: Formal and transcendental logic Den Haag, Nijhoff. The crisis of European science and transcendental phenomenology: An introduction to phenomenological philosophy Evanston, Ill. Vorlesungen Den Haag, Nijhoff.

Adolph Reinach Philosophy and Phenomenological Research Introduction to the Logical Investigations: Lectures, summer semester, Den Haag, Nijhoff. Formale und transzendentale Logik I: Eine psychologische Untersuchung, Wien Husserliana. Max Scheler in Bildzeugnissen und Dokumenten dargestellt, Hamburg: Ideas pertaining to a pure phenomenology and to a phenomenological philosophy III: Phenomenology and the foundations of the sciences Den Haag, Nijhoff.

Ideas pertaining to a pure phenomenology and to a phenomenological philosophy I: General introduction to a pure phenomenology Den Haag, Nijhoff. Adolf Reinach - obituary notice: Kant-studien 23 , pP. An International Journal of Philosophy 3. Studien zur Arithmetik und Geometrie: Texte aus dem Nachlass Den Haag, Nijhoff. Four letters from Edmund Husserl to Hermann Weyl: Consequently, the determinable X is apt to lead us back through time towards the original situation where the reference of the relevant unified series of successive intentional horizons was fixed, like for instance the occasion of the subject's first perceptual encounter with a particular object: In a more recent terminology, one may say that in this perceptual situation the subject has opened a mental file about a particular object cf.

The same goes for cases of perceptual judgements leading to, or taken by the respective subject to be confirming, entries into an already existing file. See Beyer , sec. On this reading of Husserl's notion of the determinable X , there is a link, at least in the case of proper names and in the ubiqituous indexical case, between intentional content including determinable X on the one hand, and extra-mental reality on the other, such that intentional content thus understood determines reference in much the same way more recent externalist theories of content would have it, i.

Notice, however, that Husserl does not naively take the existence of an extra-mental referent for granted. Instead, he asks which structures of consciousness entitle us to represent the world as containing particular objects transcending what is currently given to us in experience see Sections 7 and 8 below.

Husserl can thus be read or at least be rationally reconstructed as both an early direct reference theorist headword: This may help to explain why the species-theory of content had become less important to Husserl by the time he wrote Ideas.

It may be regarded as a radicalization of the methodological constraint, already to be found in Logical Investigations , that any phenomenological description proper is to be performed from a first person point of view, so as to ensure that the respective item is described exactly as is experienced, or intended , by the subject.

Now from a first-person point of view, one cannot, of course, decide whether in a case of what one takes to be, say, an act of perception one is currently performing, there actually is an object that one is perceptually confronted with. For instance, it is well possible that one is hallucinating. From a first-person point of view, there is no difference to be made out between the veridical and the non-veridical case—for the simple reason that one cannot at the same time fall victim to and detect a perceptual error or misrepresentation.

That is to say, the phenomenological description of a given act and, in particular, the phenomenological specification of its intentional content, must not rely upon the correctness of any existence assumption concerning the object s if any the respective act is about. This is supposed to enable the phenomenologist to make explicit his reasons for the bracketed existence assumptions, or for assumptions based upon them, such as, e.

In Section 7 we shall see that Husserl draws upon empathy in this connection. By contrast, there may be some such contents, even many of them, without intentional content generally having to be dependent on a particular extra-mental object. The phenomenologist is supposed to perform his descriptions from a first-person point of view , so as to ensure that the respective item is described exactly as it is experienced.

Now in the case of perceptual experience one cannot, of course, both fall victim to and at the same time discover a particular perceptual error; it is always possible that one is subject to an illusion or even a hallucination, so that one's perceptual experience is not veridical.

Edmund Husserl

If one is hallucinating, there is really no object of perception. However, phenomenologically the experience one undergoes is exactly the same as if one were successfully perceiving an external object. Therefore, the adequacy of a phenomenological description of a perceptual experience should be independent of whether for the experience under investigation there is an object it represents or not.

Either way, there will at least be a perceptual content if not the same content on both sides, though. It is this content that Husserl calls the perceptual noema. Phenomenological description is concerned with those aspects of the noema that remain the same irrespective of whether the experience in question is veridical or not.

- Husserl, Edmund, - Credo Reference.

- Husserl, Edmund.

- Edmund Husserl (1859-1938).

- Ethische Argumente gegen den Theismus ausgehend von den Texten Sartres und Russels (German Edition)!

However, this lands him in a methodological dilemma. This is the first horn of the dilemma. For, as Husserl himself stresses cf. This is the second horn. There are at least three possible ways out of this dilemma. First , the phenomenologist could choose the first horn of the dilemma, but analyse an earlier perceptual experience of his, one that he now remembers.

He just has to make sure here not to employ his earlier and perhaps still persisting belief in the existence of a perceptual object. Secondly , he could again decide in favour of the first horn and analyse a perceptual experience that he merely intuitively imagines himself to have. For Husserl's view on imagination see esp. The following sort of description may serve that function: It is not entirely clear if Husserl considers all of these strategies to be admissible. The third strategy—pragmatic ascent—fits in well with the way he uses to specify the common element of the noema of both veridical perceptions and corresponding hallucinations see, e.

XXII; English translation of a somewhat different version of the essay in: Something similar goes with regard to the singularity of a hallucinatory experience's noema: The specification might run as follows: The noema of a perceptual experience i is such that either 1 there is an object x that i represents in virtue of its noema, where x is to be regarded as the referent of i in all relevant possible worlds, or 2 there would be an object meeting condition 1 if i were veridical.

Notice that on the above-proposed externalist reading of Husserl's notion of intentional content, the noema will differ depending on whether condition 1 or 2 is satisfied. If there is no such object, condition 2 will be satisfied—provided that we are dealing with a perceptual experience. Husserl regards sense impressions as non-conceptual in nature. Rather, his view on perception is best characterized as a sophisticated version of direct i. Finally, we should note that on Husserl's view there is a further important dimension to perceptual experience, in that it displays a phenomenological deep- or micro-structure constituted by time-consciousness Husserliana , vol.

This merely seemingly unconscious structure is essentially indexical in character and consists, at a given time, of both retentions , i. It is by such momentary structures of retentions, original impressions and protentions that moments of time are continuously constituted and reconstituted as past, present and future, respectively, so that it looks to the experiencing subject as if time were permanently flowing off.

There is still something left at this point, though, which must not, and cannot, be bracketed: These recurrent temporal features of the horizon-structure of consciousness cannot be meaningfully doubted. Hence, there is no epistemically problematic gap between experience and object in this case, which therefore provides an adequate starting point for the phenomenological reduction, that may now proceed further by using holistic justification strategies.

After all, intentional consciousness has now been shown to be coherently structured at its phenomenologically deepest level. One of the main themes of transcendental phenomenology is intersubjectivity. Among other things, it is discussed in considerable detail in the 5 th of the Cartesian Meditations and in the manuscripts published in vol. According to Husserl, intersubjective experience plays a fundamental role in our constitution of both ourselves as objectively existing subjects, other experiencing subjects, and the objective spatio-temporal world.

Transcendental phenomenology attempts to reconstruct the rational structures underlying—and making possible—these constitutive achievements. From a first-person point of view, intersubjectivity comes in when we undergo acts of empathy. Intersubjective experience is empathic experience; it occurs in the course of our conscious attribution of intentional acts to other subjects, in the course of which we put ourselves into the other one's shoes. In order to study this kind of experience from the phenomenological attitude, we must bracket our belief in the existence of the respective target of our act-ascription qua experiencing subject and ask ourselves which of our further beliefs justify that existence-belief as well as our act-ascription.

It is these further beliefs that make up the rational structure underlying our intersubjective experience. Since it takes phenomenological investigation to lay bare these beliefs, they must be first and foremost unconscious when we experience the world in the natural attitude. Among the fundamental beliefs thus uncovered by Husserl is the belief or expectation that a being that looks and behaves more or less like myself, i. So the belief in question must lie quite at the bedrock of my belief-system.

Crisis , against which my practice of act-ascription and all constitutive achievements based upon that practice make sense in the first place, and in terms of which they get their ultimate justification.

Edmund Husserl - Wikipedia

Husserl's notion of lifeworld is a difficult and at the same time important one. It can roughly be thought of in two different but arguably compatible ways: However, in principle not even beliefs forming part of a subject's lifeworld are immune to revision. These conceptions determine the general structure of all particular thing-concepts that are such that any creature sharing the essential structures of intentional consciousness will be capable of forming and grasping them, respectively, under different lifeworldly conditions. That is, it has value for me with respect to the fact that with it I can produce the heating of a room and thereby pleasant sensations of warmth for myself and others.

One of the constitutive achievements based upon my lifeworldly determined practice of act-ascription is my self-image as a full-fledged person existing as a psycho-physical element of the objective, spatio-temporal order.

This self-image can be justified by what Edith Stein, in a PhD thesis on empathy supervised by Husserl Stein , has labelled as iterated empathy , where I put myself into the other subject's shoes, i. In this way, I can figure out that in order for the other subject to be able to ascribe intentional acts to me, he has to identify me bodily , as a flesh-and-blood human being, with its egocentric viewpoint necessarily differing from his own.

This brings home to me that my egocentric perspective is just one among many, and that from all foreign perspectives I appear as a physical object among others in a spatio-temporal world. So the following criterion of subject-identity at a given time applies both to myself and to others: However, Husserl does not at all want to deny that we also ascribe experiences, even intentional ones, to non-human animals. This becomes the more difficult and problematic, though, the less bodily and behavioural similarity obtains between them and ourselves.

Husserl studied many of these phenomena in detail, and he even outlined the beginnings of a phenomenological ethics and value theory cf. Always act in such a way that your action contributes as well as possible to the best the most valuable you recognize yourself to be able to achieve in your life, given your individual abilities and environment cf.

Even the objective spatio-temporal world, which represents a significant part of our everyday lifeworld, is constituted intersubjectively, says Husserl. The same holds true for its spatio-temporal framework, consisting of objective time and space. His question is what justifies us i. Roughly, his argument goes as follows.

In order for me to be able to put myself into someone else's shoes and simulate his or her perspective upon his surrounding spatio-temporal world, I cannot but assume that this world coincides with my own, at least to a large extent; although the aspects under which the other subject represents the world must be different, as they depend on his own egocentric viewpoint. Hence, I must presuppose that the spatio-temporal objects forming my own world exist independently of my subjective perspective and the particular experiences I perform; they must, in other words, be conceived of as part of an objective reality.

However, according to Husserl this does not mean that the objective world thus constituted in intersubjective experience is to be regarded as completely independent of the aspects under which we represent the world. For on his view another condition for the possibility of intersubjective experience is precisely the assumption that by and large the other subject structures the world into objects in the same style I myself do.

During the years in which his transcendental phenomenology took shape, he developed a number of "proofs" of this position, most of which are based upon his conception of a "real possibility" regarding cognition or the acquisition of knowledge. Real possibilities are, in other words, conceived of as more or less rationally motivated possibilities; and Husserl understands motivation in such a way that it is always someone who is motivated a certain way cf.

This is why Husserl subscribes to the following dependency thesis: The real possibility to acquire empirical knowledge regarding a contingent object A possible world, individual thing, state of affairs involving such thing; cf. Husserl also adheres to the following correlation thesis with regard to empirical reality and real epistemic possibility: If a contingent object A is real really exists , then the real as opposed to the merely logical possibility obtains to acquire knowledge regarding A cf.

From these two propositions—the dependency and the correlation thesis—he derives the conclusion that the existence of a contingent object A requires "the necessary co-existence of a subject either acquiring knowledge" regarding A "or having the ability to do so" Hua XXXVI, pp. This is nothing but "[t]he thesis of transcendental idealism [ A nature without co-existing subjects of possible experience regarding it is unthinkable; possible subjects of experience are not enough" Hua XXXVI, p. Husserl seems to regard real possibilities as epistemic dispositions habitualities , or abilities, that require an actual "substrate" cf.

At the same time, he stresses that "surely no human being and no animal" must exist in the actual world adding that their non-existence would however already result in a "change of the world" cf. One way to make sense of this would be to weaken the dependency thesis, and the requirement of an actual substrate, and to merely require what might be called real higher-order possibilities—possibilities for acquiring epistemic dispositions in counterfactual or actual cases where epistemic subjects would be co-existing—that may remain unactualized but could be actualized by someone properly taking into account a multitude of individual epistemic perspectives, by means of intersubjective experience.

But even under this reconstruction there remains a sense in which the criteria of real possibility and reality constitution, and the corresponding structure of the real world, are dependent on a "pure Ego", on Husserl's view: What counts as a real possibility, or as epistemically justified, is dependent on the phenomenological subjects reflecting about such counterfactual cases in the methodological context of the transcendental reduction and the results they arrive at in this context.

The collected works of Husserl were published over the course of several years, starting in , in Husserliana: The following works by Husserl have been translated into English, and they are listed in the chronological order of the publication dates of the German originals if these were originally published. Life and work 2. Pure logic, meaning, intuitive fulfillment and intentionality 3.

- Popular Articles?

- Dunkle Schwingen (German Edition).

- Der Schlaf und der Tod: Thriller (Niels Bentzon 2) (German Edition).

- Cultural Enrichment!

- The Kootie Kids and the Attack of the Poot Troop.

- Edmund Husserl | www.newyorkethnicfood.com!

- When Do I See God??

Indexicality and propositional content 4. Singularity, consciousness and horizon-intentionality 5. Empathy, intersubjectivity and lifeworld 8. Life and work Husserl was born in Prossnitz Moravia on April 8 th , Pure logic, meaning, intuitive fulfillment and intentionality As a philosopher with a mathematical background, Husserl was interested in developing a general theory of inferential systems, which following Bolzano he conceived of as a theory of science, on the ground that every science including mathematics can be looked upon as a system of propositions that are interconnected by a set of inferential relations.

Indexicality and propositional content However, as Husserl was well aware, the species-theory of content faces at least one serious objection. Singularity, consciousness and horizon-intentionality Husserl sees quite clearly that indexical experiences just as experiences given voice to by means of genuine proper names are characterized, among other things, by their singularity: Empathy, intersubjectivity and lifeworld One of the main themes of transcendental phenomenology is intersubjectivity.

Bibliography Primary Literature The collected works of Husserl were published over the course of several years, starting in , in Husserliana: General Introduction to a Pure Phenomenology , trans.