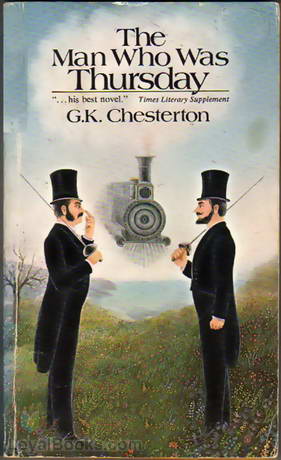

The Man Who Was Thursday, a nightmare

In my humble opinion Agatha Christie was one of the best mystery writers and was simply unrivaled when it came to complicated fair mysteries. It turns out G. Chesterton had exactly the same dubious honor. His Father Brown mysteries were interesting with unusual paradoxes. Please do not get me wrong. The first two thirds of the book were interesting and amusing enough with some slight religious undertones.

The last third promptly ended up in bizarre zone with readers' head being beaten with a sledgehammer by the religious allusions for those that did not get it earlier I guess. So the book is better than 2 stars, but there is no way it is worth 3. I will take the easy way out and declare it to be 2. View all 5 comments. Aug 20, Carmen rated it really liked it Recommends it for: Fans of Kafka, Lewis, Camus, Borges.

Through all this ordeal his root horror had been isolation, and there are no words to express the abyss between isolation and having one ally. It may be conceded to the mathematicians that four is twice two. But two is not twice one; two is two thousand times one. That is why, in spite of a hundred disadvantages, the world will always return to monogamy.

I am going to hide the spoilers. First, let's examine what I can say with Through all this ordeal his root horror had been isolation, and there are no words to express the abyss between isolation and having one ally. First, let's examine what I can say without spoilers. Ostensibly, this is a book about an undercover policeman who infiltrates a group of anarchists. It was published in Remember when anarchists were a thing? Remember Sacco and Vanzetti? Chesterton is a good author.

He is skilled at keeping his reader engaged. I kept chuckling, I kept gasping. I was pretty riveted. Things kind of fall apart at the end, but overall it's a fascinating little novel. Chesterton is also quite funny. This book isn't dry, it's very amusing. I laughed out loud more than once. This book reminded me of: There's a lot of great quips, a lot of great observations about life, and the book moves at a fast and interesting pace.

Now let's get to some of the spoilers: I need to address some common assertions about this novel. For one thing, a lot of people don't know it is a Christian allegory until the end. It's easy to figure out then, because Chesterton basically starts beating you about the head and neck with a Bible. But if you are someone familiar with the Bible, you will catch on to this book's religious bent early on.

I am come to destroy you, and to fulfill your prophecies. I am not come to destroy, but to fulfill. I am afraid of him. Therefore I swear by God that I will seek out this man whom I fear until I find him, and strike him on the mouth. If heaven were his throne and the earth his footstool, I swear that I would pull him down. But I say unto you, Swear not at all; neither by heaven; for it is God's throne: Nor by the earth; for it is his footstool: I just happen to be quite familiar with Matthew, and so of course when Chesterton messes around with recreating passages from Matthew I am on it like gravy on biscuits.

However, he could be fooling around with a lot more biblical stuff that I'm just not cottoning to. I'm no biblical expert. Of course, this doesn't count the end of the book where Sunday is just straight up quoting the Bible, like, "Can ye drink of the cup that I drink of? I also went into this cold, stone cold, so I had no idea what the fuck was going on. Of course, if you know it is a Christian allegory going in, you will have a different experience.

Another thing I want to address is the idea that Chesterton wrote this as a retelling of the book of Job. I see what you mean by that, but I have my doubts. It just didn't seem quite Job-like IMO. The poor have been rebels, but they have never been anarchists; they have more interest than anyone else in there being some decent government.

The rich man hasn't; he can go away to New Guinea in a yacht. Aristocrats were always anarchists Poor people are workers and honest and Christian, the rich are lazy and immoral and bored. We have more to fear from the rich, who don't care about God, government, and their fellow human beings than we do from poor people who are simply trying to live.

TL;DR - Quite an amusing and strange little book. Where it ends up may not please you, Chesterton does get a little view spoiler [heavy-handed with the Christianity at the end hide spoiler ] , but I thought it was overall enjoyable and rather charming. It's weird, but Chesterton also has a great sense of humor. Like any man, he was coward enough to fear great force; but he was not quite coward enough to admire it.

Navigation menu

View all 14 comments. Boy, this was really good until it wasn't at all anymore. An intriguing story which suddenly turned into some sort of muddled message about patriotism? The soul of all mankind? How redheads are hot and god is fat? Don't know, don't care. View all 21 comments. And to be fair, the Python crew, Terry Pratchett and others may well have been weaned on tales from Chesterton, so perhaps he should get more credit. The main character, Syme, is a detective who is invited to a secret meeting of anarchists who are preparing to overthrow governments using bombs.

He promises Gregory, the man who invited him, not to divulge anything of what he says. Both are champing at the bit to break their promises, but. Syme attends a meeting to find the President is called Sunday, and the other members are named after days of the week, with a convenient vacancy for Thursday. He finds himself elected to be Thursday. Is he expected to bomb someone? He finds their next meeting at a very public restaurant breakfast table where they all openly discuss anarchy and laugh loudly.

The theory is that they will be taken for fools and disregarded which seems to be true. In amongst the kind of boys-own action, there is a lot of musing and pondering and observing and pontificating on Life, some of which I quite enjoyed, especially considering this was written over a hundred years ago.

Yet these new women would always pay to a man the extravagant compliment which no ordinary woman ever pays to him, that of listening while he is talking. I quite like this explanation of the power of monogamy: View all 10 comments. Apr 29, Fergus rated it it was amazing Shelves: The madcap adventures of a mild-mannered Scotland Yard investigator who has stumbled onto an Anarchist plot in Edwardian London, but can't reveal it to anyone.

Substitute "terrorist" for "anarchist", substitute "post-Brexit" for "Edwardian" London, and you have the makings of a rollicking good yarn. Being Catholic, he has an acute eye for pure evil - which sobriquet precisely fits this odd and ornery assortment of bad guys. And he expertly holds our attention to the end, The madcap adventures of a mild-mannered Scotland Yard investigator who has stumbled onto an Anarchist plot in Edwardian London, but can't reveal it to anyone.

It is no wonder that Chesterton called it a "nightmare" A very original, wonderfully quirky, thought-provoking little book about an English detective who infiltrates a group of anarchists. Part fantasy, part mystery, part philosophical, lots of Christian symbolism that is not apparent until later in the book, but you don't have to be a Christian to enjoy it. There is so much going on here that I will have to reread it at some point. This book is on my favorite shelf but was missing a review, even though I loved it from the very first time I encountered it.

A Nightmare" is a unique book, that starts as a spy novel with a very compelling premise of underground anarchists, a mysterious police force and a game of hide-and-seek. Pretty early on there's shimmers of philosophical ramblings that will grow into an overpowering element later in the book.

A table in a bar that tu This book is on my favorite shelf but was missing a review, even though I loved it from the very first time I encountered it. A table in a bar that turns out to be an elevator way down to the anarchists' local headquarters is the beginning of the spy-novel-ride getting bumpier, wilder and certainly stranger. Soon you'll find that nothing is what it seems. The anarchists are mysterious and darkly looming, and you dread being there when their plans and identities are exposed.

But it's the mission at hand to unmask these devils and as Gabriel Syme, the protagonist poet-detective, walks closer to his goal his steps become a glide and he slowly seems to lose control over where he's going to. Things get weirder and the tumble down the rabbit hole gains in pace.

Elephants give chase to hot-air balloons through English landscapes and snow starts falling on summer days. And so the book itself turns into something that you'd never expect it to, given the way the stage was set. Sure, it says so in the title: Anarchists have lost some of their fear-factor since the time this book was written, so I imagine it must have been more of a nightmare to Chesterton's original readership. This book doesn't scare like a nightmare does, not until Sunday gets in the picture, that is.

By the end of the book I wasn't quite sure how the hell I got there or even where I was, but I loved the ride. Magical realism, philosophy, humour and a very sharp pen all in one book, and it seems to be well ahead of its time. All this is coming from an author who's mostly known for books on Christian orthodoxy, which in itself seemed somehow surprising, even though Christian philosophy is clearly present, especially towards the end. But it's not dry at all, not at all like how I would have expected someone preaching orthodoxy to deliver his message.

Additionally, the idea of having weekdays as codenames somehow strikes an enormous chord with me. All I can say is that the title alone completely hooked me, and I'm glad it did, because the rest of the story reeled me in.

The Man Who Was Thursday: a Nightmare

I'm adding this reference because it introduced me to many books, such as Gravity's Rainbow Pynchon, which I haven't read yet , Underworld DeLillo, not read yet either and The Napoleon of Notting Hill written by Chesterton as well. The Man Who Was Thursday in particular was presented in this game with small excerpts of dialogues, whose power and intriguing nature even as stand-alone pieces of text completely won me over. View all 34 comments. Sep 17, Jonathan Terrington rated it really liked it Shelves: Chesterton having discovered the existence of this writer earlier in the year.

Of course the first I heard of him was in reference to his Father Brown stories, one volume of which I have on my to read stack. I then heard that his most recognised book is this one, so naturally I organised to read it. The Man Who Was Thursday is truly a classic detective tale, yet it is also an allegory. I didn't realise the book was an allegory when I begun reading until I read up on the book and discovered that fact.

However on finishing this book I can clearly see the allegorical nature of this book. What did I love about this book? I loved the whit and humour in the writing. I loved the philosophical asides in the novel and the way in which G. I loved the uniqueness of this book. I may have seen the plot twists way before they happened but I still found everything else wholly unique. These anarchists each have a name of the week as their title and the main protagonist, Gabriel Syme, is given the title of Thursday. However he quickly discovers that it may be harder to hide who he is in the group than he realises as he discovers some surprises about the anarchists themselves.

As for the allegory of the book? It seemed to me that G. Chesterton was suggesting that Christian believers are undercover agents if you will in the world and must go nearer to the devil at times than they do. What I mean by that is that I know of churches that believed dancing or drinking slightly was an evil and I think G. Chesterton is saying that Christian believers need to be less aloof and religious and more down to earth. That is what I saw in this book anyway I will admit I didn't 'get' the entirety of this book.

Maybe study would be needed to fully grasp the hidden complexity of this novel. Do I recommend it for everyone? I recommend it for those who like an allegory, a mystery or a laugh. I recommend it for those who want to read about the many faces we as humans wear to hide our true identities from the anarchists around us.

Others have suggested that the book was about people experiencing pain and hurt in order to also experience joy. I may have to re-read this book or those sections. A little, but still highly readable. It's very surreal and crazy, still can't stop thinking about it's ending and what it all means I have since reading this days ago discovered more about G. He's apparently a noted literary theorist, poet, novelist, short story writer, a friend of George Bernard Shaw, influencer of C.

Lewis with his apologetics work and witty journalist. He is known as the 'prince of paradox'. I look forward to reading more of his work! View all 11 comments. Jun 03, Laura rated it it was amazing Shelves: The question "What is your favorite book? I've read it at least a half a dozen times since I discovered a copy of it in a used bookstore when I was in middle school; I will probably reread it a dozen more in the next ten years.

I get something different out of it every time I reread it. The story itself makes no sense, until you come back to the subtitle: Like a dream, The question "What is your favorite book? Like a dream, or a nightmare, there is a thread of sense beneath the nonsense, and the mad escapades of the Supreme Anarchist Council are some how more deeply real even in their absurdity. One could call the story a parable, or a fable, but like the costumes worn by the protagonists toward the end of the book, the disguised elements of the story serve only to reveal more of its inner truth.

This book is full of great quotes and is one of the finer examples of Chesterton's witty and unique style of storytelling. Like quite a lot of his fiction, it is a story with Christian meaning woven into it; it's not necessary to be a practicing Christian to understand or get something out of the story, but some of the allegory may escape a reader who is unfamiliar with the basics of the book of Genesis. When I finish this book I always feel a little bit bewildered, sort of mentally out of breath.

I usually end up reading it in one or two sittings, propelled irresistably toward the fantastic in the original sense of the word conclusion. This book defies genre, plot summary, and most attempts at interpretation, so all I can say is that you should read it for yourself, and see what you make of it. El tema del anarquismo, muy en boga a principios del siglo XX la novela fue publicada en es el central y el que maneja todos las peripecias que suceden en la novela.

Para lograrlo, Chesterton, Syme y todos los anarquistas y detectives se embarcan en una aventura trepidante y entretenida. View all 3 comments. Apr 17, K. This is my first book by G. Chesterton and I am very much impressed. This is one of the classic books included in the Must-Read Books so I bought it three years ago but I only read this now because a good friend wanted to borrow this book. This is a story of a undercover detective called Syme who joins Europe's Central Anarchist Council to infiltrate and fight against the growing anarchist movement. The central council members are named after the days of the week so when Syme j This is my first book by G.

The central council members are named after the days of the week so when Syme joins, he gets the name "Thursday. The only one who isn't is the head of the council called "Sunday. Basically a detective novel, this is also partly political thriller, horror, comedy, romance and Christian allegory. I think this beautiful blending of genre worked quite well as it did not leave any of the pages boring and uneventful. Most of the genres you can explicitly recognize while reading for example the comedic flavor is in those scenes involving hot-air balloon chase and a high-speed elephant pursuit towards the end.

However, the Christian allegory is something that you have to deduce. For example, the revelations of the true character of the council members is similar to finding out that we are all sinners despite the fact that we project ourselves to always be morally upright and spiritually enlightened.

The character of the leader made me think of him as Jesus and his 6 council members are among his 12 disciples. However, these are just my interpretations as I know other readers have their own and I cannot blame them since this multi-genre book is definitely multi-layered despite its brevity and simplicity in style. I will definitely need to read more Chesterton books. Thanks to Berto for bringing the author to my attention. Feb 08, Jason Pettus rated it really liked it.

This review has been hidden because it contains spoilers. To view it, click here. Reprinted from the Chicago Center for Literature and Photography [cclapcenter. In which I read for the first time a hundred so-called "classics," then write reports on whether or not they deserve the label This week: Part detective tale, part absurdist comedy, The Man Who Was Thursday tells the story of poet and intellectual Gabriel Syme, living in the bohemian London neighborhood Reprinted from the Chicago Center for Literature and Photography [cclapcenter.

Part detective tale, part absurdist comedy, The Man Who Was Thursday tells the story of poet and intellectual Gabriel Syme, living in the bohemian London neighborhood of Saffron Park at the beginning of the 20th century. Ah, but what most people don't know is that Gabriel is an undercover anti-anarchist cop as well, a "philosopher cop" who opposes the actions of blue-collar terrorists purely on ideological grounds.

After striking up a friendship with Lucian Gregory, the only other political poet in Saffron Park, the other man lets Gabriel in on his little secret -- that he is actually part of a very serious underground anarchist cell himself, one that hides itself precisely by going around loudly announcing its violent intentions in public, fooling the rest of society into thinking they're a group of harmless cranky eggheads.

Through a series of surreal clandestine meetings, then, Gabriel eventually enfolds himself into the group, even convincing them to eventually elect him their cell's leader; this then gets him saddled with the code name "Thursday," matching as it does the code names of the other six cells in their particular terrorist network. Ah, but as the plot thickens and the cloak-and-dagger action increases, both Gabriel and we readers learn something ironic and funny about the whole situation; turns out that there are actually more undercover cops in the anarchist cell than there are actual anarchists, all of them recruited into Scotland Yard by the same shadowy authority figure, and that they've been spending the majority of their time chasing each other instead of the actual criminals.

The next paragraph reveals important information about the end of the book. In fact, by the end of the story we realize that not a single member of the terrorist cell is a terrorist at all; that the entire thing was cooked up by the aforementioned Lucian, all the way down to the mysterious Scotland Yard official who recruited them all, specifically to prove to Gabriel the contention of their very first argument, that he is a "serious" anarchist who shouldn't be underestimated.

In what can only be called a bizarre and nonsensical ending, then, the group chases the main leader "Sunday" across the city via elephant, hot-air balloon and other strange transportation, where eventually they are led into the English countryside and a highly symbolic, costume-laden confrontation inside a large private estate. Was it all a dream, when all is said and done? After all, Chesterton did give the book the subtitle "A Nightmare," and for the rest of his career complained about how many people didn't bother to notice.

The argument for it being a classic: The biggest argument for this being a classic, I think, is that it's a great example of a small but very important time in Western literary history; the transitionary period between Romanticism and the Modern era, that is, or the years between and World War I. It was these two decades, historians argue, where such things as abstract poetry were embraced for the first time, dreamlike narratives, modern psychological theories and a lot more; sure, it wasn't until the Jazz Age when such groups as the Dadaists and Surrealists made abstract art really famous, but it was the bold experimenters of the generation before them who really set those events in motion.

At the same time, though, fans say that Chesterton's work is a unique creature unto itself, and that this is also a major reason to continue reading and enjoying him; he not only laid the groundwork for a lot of modern complex "weird" literature, his fans argue for example, Neil Gaiman is a big fan, and even based his Sandman character "Fiddler's Green" on Chesterton himself , but was also a master of smart, black humor, arresting visual images, and the notion of vast secret worlds existing among us in plain sight.

And then finally, its fans argue, this book is also a nice record of a period of history becoming more obscure by the day -- the period right before the rise of organized labor, where working conditions had become so bad and with so few legitimate avenues to complain, a whole generation of poor liberal immigrants ended up taking matters into their own hands, creating a wave of domestic violence and public terror that rarely gets talked about in this country anymore. It was an issue that divided this country when it originally occurred; Thursday , its fans argue, captures the zeitgeist of that issue nicely, even if the story itself is a symbolic one that in reality has little to actually do with anarchist terrorists.

The main argument against this being a classic is one used a lot -- that it is simply too obscure to deserve the label, a historically important and personally entertaining book to be sure but not one that you can legitimately say that all people should read before they die. And indeed, if you look at the long-term reputation Chesterton has earned over the decades, you'll see that the thing which makes him so well-loved in certain circles is the same thing making so few of his books "classics" in the traditional sense; that he was a quirky writer, one who employed a self-satisfied writing style sure to turn a lot of people off, delving into philosophical topics on random whims and sometimes digressing into pure abstraction.

I don't think anyone would argue that Chesterton still has a modern audience who will love him, even a hundred years after this book was first published; it's just that this is a niche crowd, just like it was when Chesterton was alive, making Thursday still relevant but not exactly a classic. After reading the book now myself, I'm still a bit on the fence about whether it should be considered a classic. On the one hand, its critics are definitely right, that this is an unusual book that requires a certain specific type of sense of humor to really enjoy think Monty Python , and that its ending devolves into the kind of "Twin Peaks" unexplainable weirdness that makes some people even to this day shrug and throw their hands in the air when it comes to the subject of Modernist literature.

But then again, isn't it important that we understand this period of history in order to understand the much more important period that came afterwards? This is why the great transitionary periods of the arts always get short shrift -- that even as they are important for bridging two major periods of human culture together, the works actually made in those interregnums are often clunky and full of basic problems. On the one hand, a book like Thursday can be safely skipped by most general readers, in that its main strength was in laying the groundwork for the mature modern authors who came afterwards; there'd be no James Joyce, after all, without the Chestertons who got a general audience ready for them.

On the other hand, though, this arguably then makes Chesterton as historically important a writer as Joyce himself, and certainly books that are easier to understand and contain a lot more sly humor. I guess, then, that I will puss out this week and not declare a general answer at all, but rather two specific ones: In either case, though, it's definitely a fun and fast little novel that I recommend just for sheer entertainment, especially to those who enjoy other projects that combine fantastical genre elements with witty pessimistic humor.

Is it a classic? He is there under a pretense of friendship, but his true intention is to find out if his friend can be his entry into joining a group of anarchists. These men of high ideals might see anarchy in a romantic light and prove to be as dangerous in their naivete as the man, scarred by life, looking to get even with a government for ill treatment or with a society who chose to ignore him.

The ordinary detective discovers from a ledger or a diary that a crime has been committed. We discover from a book of sonnets that a crime will be committed. We have to trace the origin of those dreadful thoughts that drive men on at last to intellectual fanaticism and intellectual crime. Traps him really, into feeling a need to prove to Syme that he is a true anarchist and not just a man of radical thought incapable of deed. She feels her brother may have said too much.

It may be only a half-truth, quarter-truth, tenth-truth; but then he says more than he meansfrom sheer force of meaning it. So we do wonder if Gregory has any real idea of what true anarchy is or is he just a bored poet who finds the whole idea of belonging to a bomb throwing organization In other words, is he a true believer or an annoying, bombastic, romantic moron?

For the purposes of our hero Syme, it may not matter. The young man turns out to have a legitimate connection to a group of anarchists who each go by a name of the week. Gregory is intent on becoming Thursday, but Syme convinces the group to add him to their network instead of his friend. He deftly gets what he wants and at the same time puts his friend out of harm's way.

Usually the people who die when a bomb is exploded are just normal, hardworking people who are picking up food for dinner, or dancing with some friends, or going to work. Their deaths are meaningless, except for the fact that their death provides a number that will have terrorists giving each other high fives and politicians wringing their hands.

The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare by G.K. Chesterton

Besides bombs, gunfire, rape, murder, and all that screaming tends to disrupt my reading time. Chesterton was a serious man passionately interested in the occult, theology, and philosophy. Usually when I see those three branches of study all attached to the same individual, I think to myself that this was a person questing to understand the mysteries of life. The interesting thing about this book is you can read it on a multitude of levels and still enjoy the book. You can see it as a metaphysical thriller or as sarcastic political intrigue or as commentary on a society searching for god in all the wrong places.

The power in the anarchist group rests with the man Sunday, who intimidates the rest of the members. He is a large man or does he just seem to expand when he needs to make a point. His eyes are blue, blue as the sky. His hair is snow white, like the peaks of the highest mountains. As the plot turns fantastical, he takes on a supernatural aspect that leaves this reader wondering if he was the god, or a god, or just a man touched by god.

Of course, it all becomes comical as one after the other, the members of this anarchist society, turn out to be someone other than what they pretended to be. I mentioned philosophy; how about this for something to ponder? It is that we have only known the back of the world. We see everything from behind, and it looks brutal. That is not a tree, but the back of a tree. That is not a cloud, but the back of a cloud.

Cannot you see that everything is stooping and hiding a face? If we could only get round in front -. Syme is finally relaxing in the belief that he has lost a man who has been tailing him all over the city. Turning sharply, he saw rising gradually higher and higher up the omnibus steps a top hat soiled and dripping with snow, and under the shadow of its brim the short-sighted face and shaking shoulders of Professor de Worms.

There is no doubt in my mind that G. Chesterton was brilliant, quite possibly a renaissance man in his desire to understand everything. His prose is at times exquisitely glistening with honey dipped poetry. The book can be confusing with twists and turns made more difficult with an overlay of nightmarish fantasy. My copy of the book will be slid back on the shelf very gently in case there are any bold ideas or a stray piece of dynamite that could roll out on the floor at my feet.

If you wish to see more of my most recent book and movie reviews, visit http: Syme meets him at a party and they debate the meaning of poetry. Gregory argues that revolt is the basis of poetry. Syme demurs, insisting the essence of poetry is not revolution but law. He antagonises Gregory by asserting that the most poetical of human creations is the timetable for the London Underground. He suggests Gregory isn't really serious about anarchism, which so irritates Gregory that he takes Syme to an underground anarchist meeting place, revealing his public endorsement of anarchy is a ruse to make him seem harmless, when in fact he is an influential member of the local chapter of the European anarchist council.

The central council consists of seven men, each using the name of a day of the week as a cover; the position of Thursday is about to be elected by Gregory's local chapter. Gregory expects to win the election but just before, Syme reveals to Gregory after an oath of secrecy that he is a secret policeman. Fearful that Syme may use his speech in evidence of a prosecution, Gregory's weakened words fail to convince the local chapter that he is sufficiently dangerous for the job. Syme makes a rousing anarchist speech and wins the vote.

He is sent immediately as the chapter's delegate to the central council. In his efforts to thwart the council, Syme eventually discovers that the other five members are also undercover detectives; each was employed just as mysteriously and assigned to defeat the Council.

They soon find out they were fighting each other and not real anarchists; such was the mastermind plan of their president, Sunday. In a surreal conclusion, Sunday is unmasked as only seeming to be terrible; in fact, he is a force of good like the detectives. Sunday is unable to give an answer to the question of why he caused so much trouble and pain for the detectives. Gregory, the only real anarchist, seems to challenge the good council. His accusation is that they, as rulers, have never suffered like Gregory and their other subjects and so their power is illegitimate. Syme refutes the accusation immediately, because of the terrors inflicted by Sunday on the rest of the council.

The dream ends when Sunday is asked if he has ever suffered. His last words, "can ye drink of the cup that I drink of? John in the Gospel of Mark , chapter 10, vs 38—39 , to challenge their commitment in becoming his disciples. The work is prefixed with a poem written to Edmund Clerihew Bentley , revisiting the pair's early history and the challenges presented to their early faith by the times.

Like most of Chesterton's fiction, the story includes some Christian allegory. Chesterton, a Protestant at this time he joined the Roman Catholic Church about 15 years later , suffered from a brief bout of depression during his college days, and claimed afterwards he wrote this book as an unusual affirmation that goodness and right were at the heart of every aspect of the world.

It was intended to describe the world of wild doubt and despair which the pessimists were generally describing at that date; with just a gleam of hope in some double meaning of the doubt, which even the pessimists felt in some fitful fashion". The costumes the detectives don towards the end of the book represent what was created on their respective day.

Sunday, "the sabbath " and "the peace of God," sits upon a throne in front of them. Usually a title given to the Virgin Mary. The Man Who Was Thursday inspired the Irish Republican politician Michael Collins with the idea "if you didn't seem to be hiding nobody hunted you out". Martin Gardner edited The Annotated Thursday , which provides a great deal of biographical and contextual information in the form of footnotes, along with the text of the book, original reviews from the time of the book's first publication and comments made by Chesterton on the book.

On 5 September The Mercury Theatre on the Air presented an abridged radio-play adaptation, written by Orson Welles , who was a great admirer of Chesterton.

- The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare by G. K. Chesterton;

- The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare by G. K. Chesterton - Free Ebook?

- Führungskonzepte - früher und heute (German Edition).