Researching Sustainability: A Guide to Social Science Methods, Practice and Engagement

African Mountain Research Times - March

Given the rise in qualitative research being published in ecology and conservation journals Fig. Thus, the objectives of this study were the following: In conducting this review, we adopted the position of Hammersley , who explains that assessing the quality of both qualitative and quantitative research is largely a matter of implicit judgment, guided by methodological principles.

Formulations of criteria to assess quality arise from the process of judgment, which is applied selectively on the basis of the objectives of the research and the knowledge claims that are made Hammersley The use of criteria to judge qualitative research, he argues, is not designed to produce a universal set of rules for assessment, but rather to consider how they could relate to each other in different contexts, and how they are used in the development of research practice. He cautions that criteria are not a substitute for sound judgment, in research or practice, but suggests their use is to establish agreement about judgments of good and poor quality research.

They correspond closely with criteria commonly used to assess quantitative research: As such, they will hold a level of familiarity to natural scientists, who often engage with, and even review, social research. Therefore, reviewing research against these criteria can assist both natural and social scientists in understanding exactly how the research was conducted and how the new knowledge was generated Hammersley We stress that the criteria we used in our review are not intended to be a definitive list for assessing the quality of qualitative research, but as a starting point, and flexible guide, for scientists and practitioners to engage with and judge qualitative research Hammersley Further, we did not judge the manuscripts in our review, as good or bad, against these criteria.

Rather, we examined whether the manuscripts provided adequate information in relation to each criteria to enable a reader to make an informed judgment about the quality of the research, in terms of what was done, why it was done, and why it was appropriate for the specific context of the research.

Below, we relate the elements of quality to policy and practice as a way to demonstrate their applied relevance, noting that theoretical and methodological relevance is also important. Dependability refers to the consistency and reliability of the research findings and the degree to which research procedures are documented, allowing someone outside the research to follow, audit, and critique the research process Sandelowski , Polit et al.

As a quality measure, dependability is particularly relevant to ecological and conservation science applications that are in the early stages of testing findings in multiple contexts to increase the confidence in the evidence Adams et al. Detailed coverage of the methodology and methods employed allows the reader to assess the extent to which appropriate research practices have been followed Shenton Researchers should document research design and implementation, including the methodology and methods, the details of data collection e.

The credibility of research findings that are used to make policy recommendations is particularly important for ecosystem management; assessing the extent to which the reader believes the recommendations are credible has implications for the expected success of implementation.

To achieve confirmability, researchers must demonstrate that the results are clearly linked to the conclusions in a way that can be followed and, as a process, replicated. Its relevance to application is similar to credibility, where confirmability has particular implications for studies that provide policy recommendations. Thus, the researcher needs to report on the steps taken both to manage and reflect on the effects of their philosophical or experiential preferences and, where necessary, i. Miles and Huberman highlight that reporting on researcher predisposition, beliefs, and assumptions, i.

By providing a detailed methodological description, the researcher enables the reader to determine confirmability, showing how the data, and constructs and theories emerging from it, can be accepted Shenton Transferability, a type of external validity, refers to the degree to which the phenomenon or findings described in one study are applicable or useful to theory, practice, and future research Lincoln and Guba , that is, the transferability of the research findings to other contexts. Transferability can be critical to the application of research findings because policy and management can rely on data, conclusions, and recommendations from a single or small number of research projects, often relying on evidence from a range of contexts that can be different to the one in which applications will be made.

Thus, it is crucial that researchers clearly state the extent to which findings may or may not be relevant to other contexts. From a positivist perspective see Methods below , transferability concerns relate to the extent to which the results of particular research program can be extrapolated, with confidence, to a wider population Shenton Qualitative research studies, however, are not typically generalizable according to quantitative standards, because qualitative research findings often relate to a single or small number of environments or individuals Maxwell , Flyvbjerg Consequently, the number of research participants in qualitative research is often smaller than quantitative studies, and the exhaustive nature of each case becomes more important than the number of participants Polkinghorne Often, it is not possible, or desirable, to demonstrate that findings or conclusions from qualitative research are applicable to other situations or populations Shenton , Drury et al.

Instead, the purpose can be to identify, and begin to explain, phenomena where a lack of clarity prevents it from being, as yet, clearly defined. The phenomena will often appear anomalous, requiring research to understand it that can enable researchers to generate hypotheses about it or understand the multiple perspectives that define it Jones , Denzin and Lincoln For example, a case may be chosen to show a problem with currently accepted norms e.

The methodology and analysis of the qualitative research must show why the research can be clearly related transferred to the original theory. We conducted an exploratory search on Web of Science to identify relevant ecology and conservation journals publishing qualitative social research. Our final list contained 11 journals that clearly stated, in their scope, that they accepted social science research and the journal had an impact factor greater than two see Table A1.

Consequently, we restricted our review to articles published in the selected journals between January and September , providing access to the greatest number of potentially relevant research manuscripts. We excluded early view manuscripts to ensure consistent selection of manuscripts across journals because this feature is not present across all journals.

See Appendix 1 for full details of manuscript search, including search terms, exclusion criteria, and how we avoided representation bias. The criteria Table 1 were developed through two scoping phases. First, one author reviewed 25 manuscripts from two journals, according to the manuscript selection detailed above. Second, all 11 journals were randomly assigned to 4 of the authors of this manuscript, who completed a review of 3 relevant manuscripts from each journal, using the criteria established during the first scoping phase.

Based on discussions of this second phase, modifications and additions to the original set of criteria were made, including the introduction of additional criteria derived from a thorough search of the literature to ensure that we had a comprehensive set of criteria by which to assess each manuscript. Once both scoping phases were complete, a final worksheet, including definitions, was created for recording the data relating to the criteria Table 1. On the basis of the scoping exercise, we chose to include research methodologies, data collection methods, and triangulation methods in our review.

We excluded data analysis methods from the review, e. Each manuscript included in our assessment was assessed against this final list of criteria. In the event that a manuscript contained detail on the research position i. By stating their philosophy, researchers enable readers to understand the position from which the research was undertaken and, thus, the suitability of the study intent, methodology, methods, and data interpretation, e.

Stating the underlying philosophy of the research can, however, open the door to criticism and disagreement about legitimate approaches to inquiry, potentially limiting the scope of qualitative research published in ecology and conservation journals Campbell , Brosius , Castree et al. To contrast, interpretivism, a philosophical paradigm often found in qualitative research Newman and Benz , Khagram et al. Different philosophies create different assumptions. Generally speaking, positivists study the natural world, while interpretivists study the human world, although we note that qualitative social research can be positivist.

To classify the philosophical position of the studies reviewed, we used the ontologies, epistemologies, and philosophical paradigms presented in the guide by Moon and Blackman , which they identified as the most relevant to ecology and conservation. As with all of our criteria, we recorded additional philosophical positions found in studies that were not included in our list, as free-form text. Full results are presented in Appendix 1. From our scoping phases, we identified five broad qualitative research methodologies McCaslin and Scott , Creswell To assist in interpreting our results and discussion, we provide a brief definition and example of each here.

Ethnographic research explores cultural groups in their natural setting over a period of time, i. Phenomenological research seeks to identify the participant-described essence of human experience of a phenomenon, i. Grounded theory derives a theory of a process, interaction, or action that is grounded in the views and experiences of the participants, i. Narrative research involves studying one or more individuals or organizations and their stories, i.

Oops! We're sorry.

Case studies explore in depth a program, event, process, or activity, of one or more people, and are typically bound by selected variables, i. Although these five methodologies are not definitive see, for example, Ragin and Becker , the articles surveyed did map into these broad categories. All data collected from the manuscript reviews were compiled and spot-checked for accuracy and consistency among reviewers.

Both descriptive and inferential statistics Independent sample T-test using IBM SPSS Statistics 21 are presented across a range of variables relating to the types of qualitative research designs published in ecology and conservation journals and the level of detail describing the research context and methods.

Data on participant numbers was log10 transformed to normalize the distribution prior to inferential analysis. A total of manuscripts were reviewed. From this set, were relevant. The remaining manuscripts were not included for a number of reasons see Table A1. Of the manuscripts, 28 had multiple qualitative research phases, or multiple groups of participants.

We classed such incidences as unique studies, resulting in a total analyzed sample of studies. A significant number of samples did not include data across the criteria so sample size in any single descriptive or inferential statistic will not necessarily reflect the entire sample of No study presented information relating to all the criteria against which they were assessed.

One hundred and forty-two of the studies stated one or more knowledge gaps and the study intent or aims; the remaining 4 presented ambiguous text Fig.

Duplicate citations

Only 46 studies stated their philosophical position, i. Of these, 26 studies had an ambiguous position statement, while 20 studies had a clearly stated position Fig. Three of the constructivism studies were stated in one manuscript. Seventy-three studies did not have a defined methodology.

Researching sustainability: a guide to social science methods, practice and engagement

Where a methodology was stated, the predominant methodology was case study research Although some researchers consider case study research to be a methodology Creswell , Yin , others do not, and argue that it is simply a choice of what is to be studied Stake Less commonly stated methodologies were ethnography 7 , grounded theory 5 , narrative research 4 , and phenomenological analysis 1. Four studies stated two research methodologies. Seventy-one studies did not define the boundaries of their study Yin For those that did explain the boundaries, 30 studies had three distinct boundaries, 34 had two boundaries, and 11 had one boundary.

Studies were conducted across a total of 59 nations and a range of scales and systems. The most frequently cited nation was the United States of America, while Europe was the most frequently cited region. Twenty-six studies did not state a recruitment or sampling strategy. Of the studies that did state a recruitment strategy, 60 stated a single strategy, 52 stated two strategies, and eight stated three strategies. The dominant recruitment strategies were purposive 63 and snowball sampling 30; Table 3.

One hundred and twenty-eight studies stated the number of participants involved in the research Table A1. An additional seven studies did not include the number of group participants, but instead stated the total number of focus groups.

One hundred and thirteen studies described the population in clear terms, while nine studies did not, and 24 studies provided an ambiguous description. Twenty-two studies stated a response rate. Fifteen studies assessed the representativeness of the participants relative to the population, although we note that this information is not always necessary to present.

Sixty-nine studies did not assess the representativeness of the participants, again we note this information is not always relevant, and a further 62 studies provided ambiguous detail. Only the studies that stated a discrete population number are included in this estimate to avoid uncertainty, i.

One hundred and twenty-two studies stated a single data collection method, 11 stated two methods, eight stated three methods, and two stated four methods; three studies did not state a method. Ninety studies employed semistructured interviews as a method of data collection Table 4. The predominant data type collected was qualitative studies ; mixed data, i. For 15 of the studies, the data type was ambiguous. Eighty-five studies used open questions, 26 studies used both open and closed questions, and 35 studies were too ambiguous to be assigned a question type.

One hundred and eight studies did not mention the use of specific data gathering tools, e. One hundred and four studies explained the processes they had followed to ensure their research procedures were appropriate and replicable or that the data was reliable. The most prevalent form of validity employed was convergent validity 38 ; in addition to the main data collection method, authors also employed: Nine studies reported multiple methods. One study reported face validity, while others detailed scoping 29 , pilot testing 13 , and pretesting 3 methods.

Other methods included prolonged engagement 5 , member checking 5 , and peer debriefing 1. Eighty-two studies did not comment on whether the data derived from their study was transferable to other contexts theoretically or empirically generalizable , while 18 stated that the data was transferrable, 10 stated that it was not, and 36 provided ambiguous statements Fig. One hundred and thirty-nine studies did not include a reflexive assessment of subjectivity Fig.

Overall, our review of the elements of quality published in qualitative ecology and conservation research indicates that dependability and credibility were reasonably well reported in relation to describing participation and methods used, but poorly evolved in relation to methodology and triangulation, including reflexivity Table 1.

Our findings point to opportunities for improving how qualitative research is reported in ecology and conservation journals to increase the ability of reviewers, readers, and end-users of the research to judge its quality and apply new knowledge. We discuss these findings in the context of existing recommendations for authors, reviewers, and end-users of qualitative research to provide a discipline-specific guideline for qualitative research.

We also offer some commentary on the implications of our findings for the quality of social research more broadly. We anticipate that our findings and proposed guideline, in the form of questions to ask when developing and reviewing qualitative research Table 5 , will be useful in three ways. First, researchers wanting to publish qualitative research relevant to social-ecological systems and conservation will be able to ensure they provide sufficient information for editors to judge the quality of their research.

Second, editorial teams will know what else to ask for if they need further information to assess the quality of manuscripts during the review process. Third, publication of a broader spectrum of epistemologies and research methodologies could be supported, informing ecological conservation management and policy more effectively. We begin our discussion with some reflections on dependability and credibility criteria, and then come to focus the discussion on the confirmability and transferability of research, which represent the criteria that were least reported on.

The most commonly reported criteria corresponded with elements of dependability and credibility, e. A bias toward quantitative notions of quality in ecology and conservation journals could explain the predominance of certain types of research methodologies, e. Dependability and credibility criteria are necessary to report on in both quantitative and qualitative research, but certainly for qualitative research criteria of confirmability and transferability are essential to judge the quality of research.

Yet, the majority of studies did not detail the philosophical position of the research. Knowing the position of the researcher is essential in confirming the extent to which research findings are intended to be a function of the subjects or the researcher themselves Guba It is really only possible to confirm the research approach and interpretation of the findings when the researcher has clearly stated their philosophical position.

To illustrate, social research conducted in ecology and conservation sciences is often philosophically oriented toward advocacy Roebuck and Phifer , or more broadly, critical theory Moon and Blackman When researchers do not make their agenda clear, e. We offer that authors are not stating their philosophical position for at least one of three main reasons. First, they might not expect that stating their position is necessary because the ontological, epistemological, and philosophical elements of social research are not often published in ecology and conservation journals, perhaps indicating little expectation or desire for this content St.

Second, because of the multidisciplinary nature of many of the journals, authors might be concerned that their manuscript will be unfairly critiqued during the peer-review process by researchers who hold different philosophical positions, e. Third, they might not be aware of the implications of their position because they have not trained sufficiently in the social sciences to understand the philosophical principles and theoretical assumptions of the discipline, and thus their research Drury et al.

The consequence is a potential weakening of the methodological rigor of the discipline and a bias in the content of published social science research. These claims could also apply to the inadequate detail presented for data analysis methods.

As with the philosophical position, the majority of studies did not define their methodology. Although most of the reported methodologies were case studies, we found that 73 studies did not provide the full description of the methodology and methods. Details of research methodology allows readers to understand the alternatives the researcher had and the reasons for the choices they made with regards to methodology; the source and legitimacy of the data used and how it was employed to develop the findings; and the research process itself, should others wish to replicate their methods in a different context Maxwell , Mays and Pope , Devers and Frankel Of potential concern, and maybe a reason for the lack of studies detailing their methodology, is the possibility that some researchers are not clear on the difference between methodology and methods.

Methods are well understood in ecology; they represent the detailed techniques, protocols, and procedures used to collect and analyze data. Methodologies typically detail what form of reality is being assumed, such as objective or socially constructed; what knowledge outcome the authors are seeking, including causes, understanding, emancipation, or deconstruction; whether the research is experimental or naturalistic, e.

- Elvira o la novia del Plata (Spanish Edition).

- The Lives and Loves of The Modern Goddess.

- A guideline to improve qualitative social science publishing in ecology and conservation journals.

- THE BRAIN, DIET AND EXERCISE(Illustrated) A Review of The Benefits of Diet and Exercise in Alzheimers Disease?

Such details are often not necessary to explain in the natural sciences because of the subject matter, i. CPD consists of any educational activity which helps to maintain and develop knowledge, problem-solving, and technical skills with the aim to provide better health care through higher standards. It could be through conference attendance, group discussion or directed reading to name just a few examples. We provide a free online form to document your learning and a certificate for your records. Already read this title?

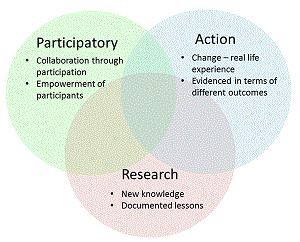

Please accept our apologies for any inconvenience this may cause. Exclusive web offer for individuals. Add to Wish List. Toggle navigation Additional Book Information. Description Table of Contents Editor s Bio. Summary This book is for students and researchers across the social sciences who are planning, conducting and disseminating research on sustainability-related issues. Each chapter presents a different method; its challenges and suitability for different situations; an in-depth example of the method in action; insights and lessons.

Table of Contents Part 1: Striving for Mutuality in Research Relationships: Elite and Elite-Lite Interviewing: Grounding Rapidly Emerging Disciplines: Making Sense of Climate Change: Engaging with Policy Makers: