The Singer: Historical Hollywood Erotica, Adult Nightclub Romance, 1930s

He investigates him and uses the carrot and stick to make him murder his wife. Planned to detail, it seems like a perfect murder. When a twenty something year old black lesbian Creole woman moves migrates from Minnesota to New York to find her freedom and independence, she encounters many exciting adventures. Not Rated 99 min Action, Crime, Thriller. Young women in the Amazon are kidnapped by a ring of devil-worshipers, who plan to sell them as sex slaves.

Some of the women escape, but are pursued into the jungle by their captors. Oswaldo de Oliveira Stars: R min Drama. A sexually frustrated suburban father has a mid-life crisis after becoming infatuated with his daughter's best friend. R 95 min Comedy. Paul Weitz , Chris Weitz Stars: Jim and his friends are now in college, and they decide to meet up at the beach house for some fun. R 96 min Comedy. It's the wedding of Jim and Michelle and the gathering of their families and friends, including Jim's old friends from high school and Michelle's little sister.

R 87 min Comedy, Music. Matt Stifler wants to be just like his big bro, making porn movies and having a good time in college. After sabotaging the school band, he gets sent to band camp where he really doesn't like it at first but then learns how to deal with the bandeez. R 85 min Comedy. Erik and Cooze start college and pledge the Beta House fraternity, presided over by none other than legendary Dwight Stifler.

R 97 min Comedy. When Erik Stifler gets a free pass to do whatever he wants from his girlfriend, he and his two best friends head to see his cousin Dwight for the Naked Mile and a weekend they will never forget. R 86 min Comedy. Moreover, it is a story about a young, frightened Sean Patrick Cannon Stars: R 92 min Crime, Drama, Romance.

Her brother Todd, doesn't approve of his upcoming brother-in-law.

- True Interracial Gangbang: Blonde College Cheerleader and the Starting 5!

- Past Regrets.

- Musical film!

- Pre-Code Hollywood;

- The Best "Erotic Drama" Films..

He wants Melinda to cancel the wedding, but for her to do that, he must get Ron to mess up. R 98 min Action, Sci-Fi. Things become complicated when her ex-lover Axel Hood, who is married to the fugitive Corrina Devonshire, re-enters her life. R min Drama, Mystery, Thriller. A violent police detective investigates a brutal murder, in which a manipulative and seductive novelist could be involved. Novelist Catherine Tramell is once again in trouble with the law, and Scotland Yard appoints psychiatrist Dr. Michael Glass to evaluate her. Though, like Detective Nick Curran before him, Glass is entranced by Tramell and lured into a seductive game.

Drama and supernatural chills in this series centered around a haunted insane asylum-turned-apartment building. PG 98 min Drama, History, Romance. Not Rated min Drama, Romance. Made of four short tales, linked by a story filmed by Wim Wenders. Taking place in Ferrara, Portofino, Aix en Provence and Paris, each story, which always a woman as the crux of the story, Michelangelo Antonioni , Wim Wenders Stars: R min Action, Comedy, Crime. R min Drama, Romance, Thriller. After hearing stories of her, a passenger on a cruise ship develops an irresistible infatuation with an eccentric paraplegic's wife.

This Showcase Original Series is an erotic anthology that explores the desires, passions and fantasies of women. R 79 min Action, Adventure, Fantasy. R 92 min Action, Drama, Romance. Teenage beauty tries to convince her new boyfriend that her father murdered her mother and that he should die too. R min Drama, Mystery, Romance. A surgeon becomes obsessed with the seductive woman he once was in an affair with.

Refusing to accept that she has moved on, he amputates her limbs and holds her captive in his mansion. After the renewed flings with their former lovers prove to be disastrously unlike the romantic memories, an unfaithful couple returns to each other. Nicola Warren , Andy J. Forest , Francesca Dellera , Luigi Laezza. R min Comedy, Drama, Romance. After a painful breakup, Ben develops insomnia. To kill time, he starts working the late night shift at the local supermarket, where his artistic imagination runs wild. R min Action, Comedy.

When a sexy, high-end escort holds the key evidence to a scandalous government cover-up, two bumbling young detectives become her unlikely protectors from a ruthless assassin hired to silence her. Not Rated 91 min Comedy, Drama. While scouting out apartments in London for her Venetian boyfriend, Carla rents an apartment that overlooks the Thames.

There she meet the lesbian hyper-horny real estate agent Moira. R min Drama, Romance. A young man searches for the proper owner of a ring that belonged to a U. R min Mystery, Romance, Thriller. A color-blind psychiatrist Bill Capa is stalked by an unknown killer after taking over his murdered friend's therapy group, all of whom have a connection to a mysterious young woman that Capa begins having intense sexual encounters with. Not Rated min Drama. Screenwriter Paul Javal's marriage to his wife Camille disintegrates during movie production as she spends time with the producer.

Far from pointing forwards, they point back, to a golden age—a reversal of utopianism that is only marginally offset by the narrative motive of recovery of utopia. What makes On the Town interesting is that its utopia is a well-known modern city. In most musicals, the narrative represents things as they are, to be escaped from. But most of the narrative of On the Town is about the transformation of New York into utopia. The sailors release the social frustrations of the women—a tired taxi driver just coming off shift, a hard- up dancer reduced to belly-dancing to pay for ballet lessons, a woman with a sexual appetite that is deemed improper—not so much through love and sex as through energy.

But the people are men—it is still men making history, not men and women together. And the Lucy Schmeeler role is unforgivably male chauvinist. It centres on Ann Miller, and she leads the others in the takeover of the museum. But the whole number is riddled with contradictions, which revolve round the very problem of having an image of a woman acting historically.

The idea of a historical utopianism in narrativity derives from the work of Ernest Bloch. They have not often taken advantage of it, but the point is that they could, and that this possibility is always latent in them. Note This chapter was originally published in spring in Movie Sociology of Mass Communications, Harmondsworth: Trilling, Lionel Sincerity and Authenticity, London: Gaines, Jane and Herzog, Charlotte eds Fabrications: Lovell, Terry Pictures of Reality, London: Williams, Linda Hard Core: University of California Press.

Broadway, vaudeville, the Ziegfeld Follies, burlesque, night clubs, the circus, Tin Pan Alley, and, to a lesser extent, mass entertainment media in the form of radio or Hollywood itself. The Forty Second Street spinoffs tended to feature a narrative strategy typical of the backstage musical: Even a radio story such as Twenty Million Sweethearts took its narrative structure from this paradigm.

Whatever the explanation for its origins, the backstage pattern was always central to the genre. The art musical is thus a self-referential form. All art musicals are self-referential in this loose sense. But given such an opportunity, some musicals have exhibited a greater degree of self-consciousness than others. Yet that merger consists not in an equal union but rather in the lending of youth, rhythm, and vitality to the stiff, formal, classical art of ballet.

Multiple levels of performance and consequent multiple levels of audience combine to create a myth about musical entertainment permeating ordinary life. In this sense musicals are ideological products; they are full of deceptions. As students of mythology have demonstrated, however, these deceptions are willingly suffered by the audience.

The ostensible or surface function of these musicals is to give pleasure to the audience by revealing what goes on behind the scenes in the theater or Hollywood, that is, to demystify the production of entertainment. The musical desires an ultimate valorization of entertainment; to destroy the aura, reduce the illusion, would be to destroy the myth of entertainment as well. Thus, a single musical number can be highly overdetermined and may be discussed under all three categories. The myth of spontaneity Perhaps the primary positive quality associated with musical performance is its spontaneous emergence out of a joyous and responsive attitude toward life.

Josh Astaire , the musical comedy director-performer, is always spontaneous and natural. Dancing is so spontaneous for Josh that animated shoes pull him into performance. The Astaire character never changes; he is presented as an utterly seamless monument of naturalness and spontaneity. Others must adapt to his style. Dinah can succeed as a performer only in a musical setting with Josh.

We are shown Cordova from the point of view of Tony and the Martons in the wings almost always a demystifying camera position , as he segues from his curtain calls as Oedipus into his offstage pomposity. Almost every spontaneous performance in The Band Wagon has a matched segment which parodies the lack of spontaneity of the high art world.

Spontaneity thus emerges as the hallmark of a successful performance. The myth of spontaneity operates through what we are shown of the work of production of the respective shows as well as how we are shown it. Even after we are shown the tools of illusion at the beginning of the number, the camera arcs around and comes in for a tighter shot of the performing couple, thereby remasking the exposed technology and making the duet just another example of the type of number whose illusions it exposes. Perhaps the ultimate in spontaneous evolution of a musical number occurs in The Barkleys. As they spin, there is a dissolve to the same step as part of an elaborate production number in the new show.

Technical or personal problems prevent the completion of every number shown in rehearsal, as when Tony walks out or when Cordova is levitated by the revolving stage. Musical entertainment thus takes on a natural relatedness to life processes and to the lives of its audiences. Musical entertainment claims for its own all natural and joyous performances in art and in life. In Ziegfeld Girl , Lana Turner is destroyed when she forsakes the simple life in Brooklyn for the glamour of the Follies.

Successful performances are intimately bound up with success in love, with the integration of the individual into a community or a group, and even with the merger of high art with popular art. This consummation takes place on the stage at the premier in front of a live audience and in the form of a duet. This hall-of- mirrors effect emphasizes the unity-giving function of the musical both for the couples and audiences in the film and for the audience of the film.

Gaby, in The Band Wagon, learns the value of popular entertainment as she learns to love Tony. The number combines the ballet movements associated with Gaby and her choreographer beau Paul Byrd with the ballroom dancing associated with Astaire. The arcade sequence repeats this opening movement. Once again Tony overcomes his sense of isolation by reestablishing contact with an audience through spon- taneous musical performance. We first see Gaby in a ballet performance in which she functions as prima ballerina backed by the corps.

Cordova prevents a terminal clash between Tony and Gaby by rushing into the neutral space of the front hall and drawing the representatives of both worlds back into his own central space. Paul Byrd draws Gaby away from the group into an isolated space symbolic of the old world of ballet; the camera frames the couple apart from the mass.

In leaving this isolated space to return to the group, Gaby has taken the side of the collective effort which will produce the successful musical. Even the musical arrangement of the song—upbeat and jazzy—contrasts with the more sedate balletic arrangement we heard in that rehearsal for the Faustian Band Wagon in which Tony dropped Gaby.

It offers a vision of musical performance originating in the folk, generating love and a cooperative spirit which includes everyone in its grasp and which can conquer all obstacles. The myth of the audience It follows that successful performances will be those in which the performer is sensitive to the needs of his audience and which give the audience a sense of participation in the performance. Tony Hunter, on the other hand, is willing to leave the self- enclosed world of the theater to regain contact with the folk who make up his audience.

The insensitive performer also attempts to manipulate his audience. Lina Lamont masks the fact that she is unable to speak for herself either on stage or on screen. Yet while setting up an association between success and lack of audience manipulation, the musicals themselves exert continuous control over the responses of their audiences. The film musical profits rhetorically by displacing to the theater the myth of a privileged relationship between musical entertainment and its audience. Hollywood had only the limited adaptations made possible by the preview system and the genre system itself which accommodated audience response by making or not making other films of the same type.

The backstage musical, however, manages to incorporate the immediate angle, and we see the couple taking a bow before a live audience. MGM musicals make use of natural, spontaneous audiences which form around offstage performances. Audiences in the films suggest a contagious spirit inherent in musical performance, related to the suggestion that the MGM musical is folk art; the audience must be shown as participating in the production of entertainment. Intertextuality and star iconography can be a means of manipulating audience response. Both the myth of integration and the myth of the audience suggest that the MGM musical is really a folk art, that the audience participates in the creation of musical entertainment.

The myth of integration suggests that the achievement of personal fulfillment goes hand-in-hand with the enjoyment of entertainment. Entertainment, the myth implies, can break down the barriers between art and life. The myth of entertainment, in its entirety, cannot be celebrated in a single text or even across three texts. It might be said that the elements of the myth of entertainment constitute a paradigm which generates the syntax of individual texts.

That is, why expend so much effort to celebrate mythic elements the audience is likely to accept anyway?

Answering this question involves an awareness both of the function of ritual and of the ritual function of the musical. At a time when the studio could no longer be certain of the allegiance of its traditional mass audience, The Band Wagon, in ritual fashion, served to reaffirm the traditional relationship. For the musical was always the quintessential Hollywood product: Faced with charges of infantilism from the citadels of high art, the studio could suggest, through The Barkleys of Broadway, that all successful performances are musical performances.

Faced with the threat of changing patterns of audience consumption, the studio could suggest, through The Band Wagon that the MGM musical can adapt to any audience. Self-reflexivity as a critical category has been associated with films, such as those of Godard, which call attention to the codes constituting their own signifying practices. MGM musicals have continued to function both in the popular consciousness and within international film culture as representatives of the Hollywood product at its best.

I hope to have shown that this was the very task these texts sought to accomplish. Basic Books, , p. Yale University Press, , p. Even the supposedly Brechtian antimusical Cabaret merely inverts the backstage paradigm, while maintaining its narrative strategy. All our experience predisposes us toward a particular way of viewing. The very vocabulary we use to describe narrative reveals a great deal about our presuppositions. Indeed, all our notions about narrative structure seem to support this proposition.

The concept of motivation is thus essential to this standard view of narrative structure. It is of course not possible to prove that one event causes another, any more than we can prove that a moving billiard ball striking a stationary ball causes the stationary one to move. The traditional approach to narrative solves this problem by postulating psychological motivation as a necessary and sufficient connector. From this point of view each plot looks more or less the same. An initial impulse sets in motion a series of causally related events, each one closely tied to the preceding and following events: The camera immediately cuts to the source of this second song: At the request of the ladies on deck, an emissary soon appears to order the men in the hold to cease their singing or suffer the consequences.

What this chronological approach ignores, however, are the careful parallels set up between Jeanette MacDonald and Nelson Eddy. She sings on deck, he sings in the hold; she sings to entertain a bevy of society women, he sings to relieve the misery of a group of penniless men; she is free, he is behind bars. The first two scenes must be visualized not one after the other but one balanced against the other. Now classical narrative analysis would make the chronological relationship primary, relegating the simultaneity and parallelism of the scenes to the shadows of stylistic analysis or theme criticism.

In order to understand the musical, however, we must learn to do just the opposite; we must treat the conceptual relationships as fundamental, assuming that the rather tenuous cause-and-effect connections are in this case secondary, present only to highlight the more important parallelisms which they introduce. Yet they share one essential attribute: Two centers of power, two sexes, two attitudes, two classes, two protagonists. If this, however, is the sole function of the scene, then it is wasted indeed. What moviegoer in needed a preliminary infatuation scene to inform him that Eddy and MacDonald would ultimately fall in love?

He is still concerned about the fate of his singing friends; she still wants to be able to sing without interruption. He is all rebellious energy, caring little for social mores as long as the cause of freedom is served; she is all properness, expecting the dictates of society to be obeyed even on the high seas. As this analysis suggests, the plot of New Moon depends not on the stars falling in love they do that early on nor even on their marriage even that takes place well before the end , but on the resolution of their differences.

Each must adopt the characteristics of the other: Those aspects which form the heart of traditional narrative analysis—plot, psychology, motivation, suspense are to such an extent conventional in the musical that they leave little room for variation: Each segment must be understood not in terms of the segments to which it is causally related but by comparison to the segment which it parallels. New Moon is thus seen not as a continuous chain of well-motivated events but as a series of nearly independent fragments, each a carefully constructed duet involving the two principal personages.

To judge from the point of view of the plot, Gigi is a remarkably unimpressive affair: In fact, the scenes which follow make no sense at all unless we see them as outgrowths of the basic sexual parameter introduced by Chevalier. We observe Gigi at home, then Gaston at home; Gigi is with an older relative, so is Gaston; Gigi has no great desire to keep her appointment, neither does Gaston; Gigi is defined by female preoccupations looks, clothes, manners , Gaston by their turn-of-the-century male counterparts business, politics, riches. The following sequences further develop this paradigm.

- ?

- .

- Werther: Die Opern der Welt (German Edition).

- HOLLYWOOD MUSICALS, THE FILM READER | Hilnet Correia - www.newyorkethnicfood.com!

- Prairie Murders: Mysteries, Crimes and Scandals (Amazing Stories)?

- The Best "Erotic Drama" Films. - IMDb.

Each scene involving only one of the lovers is invariably matched by a parallel scene song, shot, event featuring the other lover. From this rather simple discovery about the structure of Gigi we can deduce certain important attributes of the interpretation process appropriate for Gigi and the American film musical in general. Traditional narrative analysis usually stresses other scenes involving the same character, but in the musical the basic context is constituted by a parallel scene involving the other lover.

Not just any bench, however; it is the very same bench used by Gigi during her earlier song. His presuppositions about the linear, cause-and-effect, psychological nature of classical narrative have blinded him to the structural patterns particular to the musical. Gigi primping b Male occupations: The episodic sequence that follows reveals Gaston perform- ing his masculine duty, hosting party after party. How do we interpret this short but effective sequence? From a psychological point of view it is all but useless, since it tells us nothing about Gaston which we do not already know; it motivates nothing which is not already moti- vated in a number of other ways.

A role for men, a symmetrical role for women: Each pairing of shots reinforces the notion that men and women alike play predetermined parts in an already written scenario. Individuals have responsibilities to their sex; the older generation must remind the younger of these responsibilities. Older characters serve not so much as go-betweens but as symbols of the conduct expected of their younger charges. We have seen thus far how every aspect of Gigi obeys a principle of duality. This rule is by no means limited to actual events.

The technique even extends to paired shots and objects: What conclusions can we reach about Gigi based on comparison of these various pairings? On careful inspection, however, we can distinguish in any musical a secondary but essential opposition alongside the primary sexual division: These secondary attributes always begin diametrically opposed and mutually exclusive.

What characteristics constantly inform the opposition of Gaston to Gigi? Two answers to this question are immediately apparent. First, we have learned that both sexes are collectors, men collecting women and women amassing jewels. Marriage is seen, according to this view, as the only way to join beauty and riches, to effect not a compromise but a merger between the dulce and the utile.

Navigation menu

Similarly, a man could not fully enjoy the charms of feminine beauty without marrying. Sexual stereotyping and a strict moral code went hand in hand, leaving only one solution for young men and women alike: In this sense Gigi, like many other musicals, is an apology for traditional mores, an ode to marriage as the only way to combine riches and beauty. On second glance, however, a minor premise of some importance becomes apparent.

She skips and hops, plays tag and eats candy; he is reserved, serious, moody. She wears a brightly colored pinafore; he has formal attire and a cane. In short, she is a child and he is a man. When they go off to the ice palace together he orders champagne for himself and the turn-of-the-century French equivalent of a milkshake for her. Now there is nothing problematic about an intergenerational relationship—unless, that is, the members of different generations suddenly develop a romantic interest in each other. And that, of course, is just what happens in Gigi.

There is something vaguely incestuous about the Gigi—Gaston relationship since they could, indeed, be related by blood. One minute she is sitting in his lap, cheating at cards and munching on caramels, the next she is being eyed, invited, and embraced as a potential sexual partner. In fact, quite to the contrary, their love affair serves to gloss over the very oppositions on which the incest taboo is based.

Children and adults are conceived as two diametrically opposed groups that allow no overlapping. Yet in order to reach maturity every individual within our society must violate the seemingly airtight partition separating the two categories. It is this problematic relationship between childhood and adulthood that Gigi mediates, with the marriage model providing the resolution: Now he eats the caramels he brings to Gigi, dances wildly around the room with Gigi and her grandmother, plays leap-frog on the beach at Trouville.

While she is becoming an adult, he is recapturing some of the excitement of youth. Beauty and riches are treated like sex-linked chromosomes, with each quality allotted to a single sex. These problematic dichotomies are eventually resolved only when the resolution of the sexual duality marriage is used as a non-rational mediatory model for the attendant thematic oppositions, bringing together categories and individuals that seemed irreconcilably opposed.

The only way for the same individual to enjoy both riches and beauty is to marry. The only way to save both childlike and adult qualities is through a merger, thus blurring the barrier between the generations, thereby erasing the spectre of incest. The plot, we now recognize, has little importance to begin with; the oppositions developed in the seemingly gratuitous song-and-dance number, however, are instrumental in establishing the structure and meaning of the film.

Seen as a cultural problem-solving device, the musical takes on a new and fascinating identity. The musical is one of the most important types of text to serve this function in American life. By reconciling terms previously seen as mutually exclusive, the musical succeeds in reducing an unsatisfactory paradox to a more workable configuration, a concordance of opposites. Traditionally, this is the function which society assigns to myth.

Rick Altman London and Boston: Routledge and Kegan Paul, , — It is a tradition based on creating feelings of abundance, variety, and wonder. Stressing aggregation rather than integration, it offers a fundamentally different approach to entertainment from those more modern forms that are oriented toward unity, continuity, and consistency.

The musical genre is in large part a holdover from such archaic entertainment forms. The genre remains in a state of unresolved suspension between spectacle and narrative, between aggregation and integration. A major aesthetic choice in a musical concerns the type of relationship it develops between these two sides of the genre. However, the format of the revue was more solid and anchored than that of its predecessors, and it offered greater opportunities for spectacle. On the one hand, the revue was not bound by the constraints of narrative consistency.

The most elaborate production concepts could be fully indulged with a minimal regard for integration, plot sequence, or simple logic. A revue could mount a Parisian number and follow it with an Arabian number, without bothering to connect the two via any narrative framework. On the other hand, a revue had available to it all the scenic and production resources of the mainstream dramatic stage. The period of the First World War and the early s was the heyday of the spectacular revue on Broadway as well as in Paris and London.

Becoming increasingly unfashionable and insolvent, the big revues lumbered through the end of the s, when the Crash and talking pictures sent them on the road to extinction. His early acclaim was based on qualities remarkably different from those for which he is now known. Berkeley came on the scene of the big Broadway revue during the period of its overripe maturity and imminent decline. Some of the most important early movie musicals were pure plot- less revues: Others, such as The Broadway Melody , winner of the Academy Award for Best Picture and Glorifying the American Girl , produced under the nominal supervision of Florenz Ziegfeld , employed backstage plots concerning the production of a spectacular stage revue.

The temporary decline in popularity of the movie musical in —32 brought with it a general demise of the pure plotless revue on the screen. However, this fact does not diminish the importance of the revue tradition in the development of Berkeleyesque spectacle on the screen. The revue impulse also extends to a range of adulterated forms that incorporate narrative while at the same time maintaining a pronounced autonomy of the musical passages.

There are several precedents for this in the history of the musical theater. This structure, although less popular during the era of the big annual revues, was still practicable enough to be employed when Berkeley worked on such late twenties Broadway revues as A Night in Venice, Pleasure Bound, and Broadway Nights. Other lightly narrativized musical forms preceded the advent of the revue proper. The celebrated spectacle Around the World in 80 Days extended the tour-of-the-town format on a global scale.

Farce-comedies appeared regularly on the New York stage from until well into the s. The previous two forms—tour-of-the-town and farce-comedy—bring the narrative from someplace outside into a place or places where a show can be performed. The backstage musical, on the other hand, works primarily from the inside, originating from the venue where the show is made and centering on the relationships between the performers who make it.

The backstage musical has always been far more popular and important on the screen than on the stage. It is remarkable how quickly the backstage form achieved maturity in the movie musical. The Broadway Melody released in February, still holds up as a classic of its form. The backstage form continued to thrive in the s, often overlapping with the musical-biography e. In the s, it provided a refuge for the spectacular, semi-autonomous production number, even in the face of a growing trend toward integrated, plot-oriented musicals: On the other hand, Babes in Arms , The Barkleys of Broadway , and Cabaret are more integration-oriented i.

By the same token, forms such as tour-of-the-town, farce-comedy, and backstage musical are by no means mutually exclusive; they easily combine and blend into one another. The common denominator that seems to be essential to the establishment of spectacle in the backstage musical is primarily a spatial one rather than a musical or narrative one.

This renders the space accessible to spectacular expansions and distortions that can be clearly in excess of the narrative without necessarily disrupting it. The main requirement is that this space be a special or bracketed space, adjoining the primary space of the narrative but not completely subordinated to it. The strong demarcation of the space of the numbers as distinct from that of the offstage narrative is an essential ingredient of Berkeleyesque cinema. It is overdetermined in a very particular way. This hierarchy is surmounted by a dominant discourse that resolves or rationalizes all the other discourses and provides a frame of reference off which they can be read.

In classical narrative cinema, this dominant discourse is the main narrative line. This type of discursive divagation might be kept more deliberately ambiguous or outright contradictory in other forms of cinema, such as European art cinema, politically radical cinema, and avant-garde cinema. The narrative and the musical numbers appear to be based on different laws or ground rules. Typical examples of this impossibility include: These films all feature several musical numbers, but the numbers do not create sustained problems in terms of a dominant realistic discourse.

There are no or hardly any impossible numbers; the numbers can all be rationalized on the level of the narrative as professional stage performances or prerehearsed routines. It has already been clearly established in the narrative that Brad is a songwriter engaged to write tunes for the show and that he has been working on this and other songs. He performs the number seated at his piano, with a music sheet in front of him and a pencil, presumably still warm with inspiration, lodged behind his ear.

The major shift in discourse in these films occurs not in the transition from narrative to performance but within the performance itself. These impossibilities occur on two main levels: This distinction is then doubled and reinforced in spatial terms: This allows full, unrestrained indulgence and extension of the impulse toward spectacle, toward the Berkeleyesque.

This separation occurs not only spatially and discursively, but also economically, presenting a world of opulence and excess in contrast to the world of struggling chorus girls and Depression hard times in the narrative passages. This is accomplished by two complementary strategies: The former effect is accomplished by a reduction of scale and a naturalizing of musical performance style.

The latter effect is enhanced by the use of polished dialogue and syncopated line deliveries that seem almost as stylized as song lyrics. In addition, everyday activities and environments are sometimes denaturalized by being set to choreographed rhythms e. As a result, the gap between the performance world and the narrative world, though not eliminated, is narrowed and smoothed over.

Instead, any place becomes a potential performance space: Transitions from narrative to performance are stylized and impossible in the I-feel-a-song-coming-on mode, leading to an encroachment of performance discourse into narrative discourse. However, this discursive rupture is then smoothed over by the consistencies of tone, style, and scale between the narrative and the musical- performance passages. In effect, Berkeley spectacularizes the camera. Just as the structure of the Berkeleyesque musical severs the domain of the production numbers from that of the narrative, the camera itself is liberated from the demands of narrativity and, to a degree, from the demands of any form of subordinate expressivity in order to assert its own presence as an element of autonomous display—that is, of spectacle.

It also applies more generally to those situations where realistic consistency is violated for the sake of producing a cinematic effect. Technique in classical cinema is subordinated to and largely absorbed into the narrative. Editing, camera angle, camera movement, optical effects, and other cinematic devices are freed from the constraints of realistic, narrativized, cause- and-effect discourse and become liberated elements of play and display.

Cut loose from the space and discourse of the narrative, they are free to soar into the realms of pure design and abstraction. His contribution to the evolution of the movie musical can be seen not so much as the replacement of a theatrical mode by a cinematic one, but as the extension and expansion of a theatrical tradition—the Tradition of Spectacle—to include specifically cinematic elements. A Chronicle New York: Oxford University Press, , p.

Dutton, ; reprint ed. Vintage Books, , p. In backstage stories, directors, songwriters, and spectators are typically men, whereas women are objectified as the show, with the all-female chorus line, dressed in extravagant costumes, often made inseparable from the set. However, does it necessarily follow that, even in a Berkeley musical, the genre simply reproduces without problematizing a patriarchal ideology which subordinates the female body to the gaze of a male voyeur?

The essays in this section argue for a more complex understanding of how the musical represents gender in spectacle. According to Mellencamp, sexual difference organizes many other differences to sustain what she refers to as the textual economy of Gold Diggers. But this does not result in a unified text that successfully manages the ideological representation of gender. The Berkeley production numbers, by contrast, define heterosexuality through the female body, which they equate with technology and capital exchange.

Their reading draws implicit attention to the similarity of Blondes and Gold Diggers: The first two pieces examine musicals centering on showgirls, that is, women who make their living performing in stage shows for the benefit of men. As Cohan demonstrates, an Astaire number, whether solo or duet, halts or exceeds the linearity of narrative to put the dancer in the position conventionally occupied by a female performer like Monroe or a Berkeley showgirl, but not with the effect of effeminizing him.

Using Royal Wedding and Silk Stockings to illustrate, Cohan analyzes how the numbers in these films reinforce the unconventional masculine persona which Astaire projected as the leading male dancer in musicals. Wages were 33 percent lower than in In spite of this decline in income, movie attendance was estimated at between 60 to 75 million per week.

To paraphrase one critic: Their musicals, born of the depression, combined stories of hard-working chorus girls and ambitious young tenors with opulent production numbers. Lighting was low key. Cutting corners became an art. Stars were contracted at low salaries. Therefore, a few details are in order. Unions were just beginning to gain power and demand benefits. This was the era before Social Security, unemployment and health insurance, minimum wage, and other labor laws that prescribed working hours and conditions.

Demon- strations by the employed occurred around the country, often involving violent encounters with the police. On March 7, , three thousand protesters marched on the Ford factory, demanding jobs. In Toledo a large crowd of the unemployed marched on grocery stores and took food.

The Soviet revolution had occurred less than two decades earlier. He enacted Social Security in — The signs of economic chaos and poverty like street people in the s visibly exposed the gap between rich and poor.

Pre-Code Hollywood - Wikipedia

An estimated seventy thousand children were homeless, living in shantytowns. Rather than interpreting these events as economically and socially determined, thereby questioning capitalism, some members of Congress viewed them as personal—inspired and instigated by Communists—and created a committee to investigate radical activities.

It should be pointed out that Hollywood unionized early and thoroughly, with the exception of studio executives and producers; by the mids, there were guilds for writers, actors, directors, and cinematographers. Gold Diggers is symptomatic of these issues of unemploy- ment and homelessness. In this number, demarcating wipes, like stage curtains, separate the acts of history.

This number explains the Depression as a product of World War I. As Carol Joan Blondell sings: You sent him away. Just look at him today. The long lost dollar has come back to the fold. He and his men literally strip the women of their costumes. Thus police are rendered harmless, their image contained but still suggestive. The speakeasies where Trixie and Carol seduce J. Lawrence Bradford and Fanuel Peabody also refer to Prohibition. Like classical Hollywood film and musical comedy in general, the film operates to proclaim, then contain, female sexuality.

It moves from single women and men, separated by class to a triad of perfectly paired, married classless couples. This process takes women out of the erotic spectacle and perhaps also the labor market and into marriage and respectability. There is a moral for women in the last sequence: For women, being without a man is indeed a barren fate, worse than death or high-contrast German expressionist lighting.

They have the talent and the brains but not the bucks or the power. I was happy then. He used to take care of me. This is paralleled by J. Thus the inequities of both class and gender are collapsed into marital salvation. By uniting the working-class chorus girls Polly [Ruby Keeler] tells us in the upper-class nightclub scene on the balcony that her father was a postman with upper-class, inherited wealth in a backstage triple whammy of Polly and Brad, Trixie and Fanuel, and Carol and J.

Lawrence, presumably the nation will be restored. Other cultural, social differences—the inequities of class, race, politics, economics, and age—are secondary. Lawrence, has top billing, albeit less screen time and the eager tenor Dick Powell, in this instance portraying Brad Roberts or Robert Bradford. Lawrence and Fanuel are naive and inept, hardly savvy corporate scions. They are shown at their club, not at work. They are the representatives of inherited rather than earned wealth. Or one can imagine marital rescue after a spending spree on luxury items as a fantasy of the historical women in the audience—with few other options available to them in the s.

The marital inevitability is manipulated by the women for economic pleasure and gain as much as, or more than, romance. The narrative is thus an address and an appeal to women—who are let in on the joke, which is on J. These chorus girls are not stupid, inexperienced characters, particularly Trixie: Going to an analyst became de rigueur in the industry. The three couples represent three stages of romance, a marital typology that accords with character traits: Polly and Brad represent young, innocent, virginal love; Carol and J.

Lawrence, middle-aged sexual desire and skepticism; and Trixie and Fanuel, asexual, older companionship. Significantly, because all the women are young, the age of the man defines each relationship, suggesting that our interpretation of the women is, to a degree, determined by the men. The pairing of the older man and the younger woman is the norm for cinema, rarely the reverse. I examine this later in greater depth. That these are capitalist, corporate practices is not without implication. In fact, the Berkeley sequences are spectacles of the glories of capitalist technique and hence visual demonstrations of the narrative—salvation via investment bankers.

Not only were they American products; at the same time they demonstrated the greatness of American production. As [Lucy] Fischer writes: The modernist belief that technology will bring social progress is an old and ongoing argument that can ignore social and political issues. Along with its role in industry, electricity, like the automobile and cinema, was a novelty, spectacle, and a medium of entertainment.

What is intriguing to me is the persistent contradiction between yoking the female body to either nature or technology, presumably opposite interpretations. As I argued in regarding Metropolis Fritz Lang, Germany, , the historical equation of the female body with technology, including sex, represents the female body as a special effect, one that suggests both the danger and the fascination of spectacle, an aberration that must be held in check.

However, whether as old-fashioned nature or modern high tech, the technology of gender functions to keep women in line, to serve their masters.

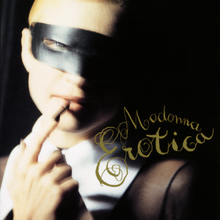

Erotica (song)

As the story is told by John Lahr, the Rockettes were the U. They first performed in St. Louis in as the Missouri Rockets: Russell Markert was the inventive, U. Installed in at the Roxy, the number of girls expanded to the thirty-two Roxiettes.

Sex & Erotic movies, ever best..

The key was group discipline and submission. Rockettes were not allowed to tan and were of the same color, white. Markert was the coach until he retired in , the dance, with the trademark kick that still elicits applause, is the same, as is their rigid, upright posture and style of movement. Interestingly enough, the analyses of various dance-line daddies are almost identical fantasies of power over women; their commentaries are as uniform as the precision female lines they order. I soon realized that the most exciting thing one could put on a stage was a breathtakingly beautiful girl.

She did not need to know how to dance or even sing. They are assembled on the stage and then segregated according to height. Then in lines of twenty, they step forward, count off, make quarter turns and face forward. The following points of beauty are given careful consideration: We replace them when it is possible. He was also, in his way, a cultural historian: This curiosity seeks to complete the sexual object by revealing its hidden parts.

Men transform female sex into art as an excuse, a cover-up for male desire. Berkeley verges on real perversion, which, in history, has turned to parody in its excess. The Birth of the Prison are perfectly apt. He outlines tactics for subjecting bodies, taking his model from the military and pedagogy: The body is constituted as a part of a multi-segmentary machine. The conventions of the classical text also function via the disciplinary techniques of repetition and difference.

Moving inevitably to resolution through an intricate balancing of symmetry and asymmetry by constant petitions and rhymings on the sound and image tracks, classical narrative meticulously follows the disciplined rules of its game. The spectatorial play of these shared conventions provides pleasure: Rhyming and repetition within Gold Diggers, as in many classical texts, is intricate. His guitar case is replicated by the Kentucky Hillbillies and is transformed into the neon image of women as violins.

The violin symbol is taken from vaudeville to the legit stage, from a lowly image to a lofty image. Like aerobics, repetition and careful instruction are as essential as the move toward closure and conclusion. From the very beginning, we await the pleasure of the end. The narrative of musical comedy coincides with classical narrative.

As in classical narratives, the work of musicals is the containment of potentially disruptive female sexuality, a threat to the sanctity of marriage and the family. First and foremost, spectacles are bracketed by complete musical scores. Music is a foregrounded code that symmetrically reoccurs as functional scoring in the narrative segments and under titles, thereby either anticipating or recalling the spectacle. Lawrence and Fanuel Peabody. The melody is next heard on the balcony while J.

Lawrence and Polly discuss her past and then in the apartment during the kissing sequences between Carol and J. Reportedly, this was another production number for Ginger Rogers as Fay Fortune , just beginning her climb to stardom and top billing, here seventh in the credits. It was subsequently cut from the released version. It is the only song that does not have its own spectacle. Remember the apartment scene with Barney and the girls. I got the idea for it last night.

I was down at Times Square, watching those men in the breadlines, standing there in the rain waiting for coffee and doughnuts, men out of a job, around the soup kitchen. In the background, Carol, the spirit of the Depression, a blues song, no, not a blues song, but a wailing, a wailing! And this gorgeous woman singing a song that will tear their hearts out. The big parade, the big parade of tears!

Because music is the dominant code, the performer could sing, dance, skate, swim, tumble, or have sex to its rhythms. Hence the term musical comedy: The opening and closing musical notes are re-marked by another system of mirrored, bracketing shots. Identical shots of theater stages, curtains rising, orchestras and conductors, and on-screen audiences open and close the spectacles.

This theatrical iconography refers both to the origins of the genre and to the spectator in the movie theater which often contained a proscenium stage with an insert screen. These bracketed and rhythmically marked spectacles, set in and apart from the overall movement of the narrative, make explicit and even exhibit certain operations that other genres work to suppress.

Spectacles can be considered as excessively pleasurable moments in musicals; ironically, the moments of greatest fantasy coincide with maximum spectator alertness. They thus function as a striptease—a metaphor that is apt for the Gold Diggers. Coitus interruptus is another. Fay Fortune is stripped of her dress, to be used as a lure for Barney: Lawrence and put him to bed.

Going to the movies used to include live performances, prologues, orchestras. The performances included a genre mixture of cartoons, news, travelogues, shorts, and features. In the s the introduction of food and drink, particularly popcorn, as well as the pleasures of air conditioning and plush decor, added to the experience.

Women went to the movies not consciously for punishment, not to identify with men, and not just for a single narrative but for multiple pleasures, including the luxuries of the upper class. As the bodies make it, we make it. Basic Books, , , Barnes, , 50— Doubleday, , — University of California Press, , 2: Bazin differentiates the American product: Angela Carter in The Sadeian Woman sees this corporate analysis differently: Michael Gurevitch and Mark R.

Ley Newbury Park, Calif.: Sage, , Also, rather than being invisible in movies, the penis has become an image or a joke on late-night TV. Thanks to Janet Staiger for this article. Hogarth, , The Birth of the Prison New York: She convinced me that I was smart enough to publish an essay.

This essay has been reprinted in Explorations in Film Theory, ed. Indiana University Press, , 3— Robert Hurley New York: Random House, , Conversely, I remember fending off roving arms that awkwardly groped in my direction. Dating and cruising are quite different seductions. The misogyny of popular art, music, theatrical arts and film interferes with our pleasure in them. This paper discusses a departure from this familiar alienation. We realized we loved the energy that Monroe and Russell exude.